Years ago, my husband Lincoln shared a memory of being taken to a cotton field as a child in the name of education and enrichment.

As he tells it, Lincoln, then a young Black boy, and a group of his predominantly white elementary school classmates were shuffled to a nearby stretch of cotton in his hometown of Farmersville—a small Friday Night Lights community once known as the “Onion Capital of North Texas.” Once at the field, Lincoln and his schoolmates were encouraged to participate in a cotton-picking competition. Yes. A cotton-picking competition. The rules were simple: whoever amassed the most cotton would be anointed the winner.

After his recollection, Lincoln and I laughed at the scene’s absurdity. And we were also gut-punched by it. By the transformation of cruelty into play. By the casual lack of forethought, concern, and context that should’ve been present when planning such an excursion. By consequential histories being easily and glibly mashed into the shape of the shrug-able and mundane.

It’s no secret or bold revelation that the cotton plant has been inscribed with memories of coerced brutality, blood-spill, and back-breaking toil among many Black people in the United States. Lincoln’s experience is one of many testimonies to that fact. An under-told episode in the long arc of cotton haunting the lives of Black folks, one that loops in my mind, involves, of all things, mattress production.

In a bid to lend a helping hand to struggling farmers amid the economic spiral of the Great Depression, the U.S. Department of Agriculture bought bales upon bales of surplus cotton from producers and jumpstarted the Cotton Mattress Program—a short-lived initiative offering volunteer-led instruction to those in rural, low-income communities on how to create their own mattresses. The intent was to lift all boats: provide a buoy for the agricultural sector while equipping folks around the country with quality bedding they likely didn’t have the means to purchase otherwise. But the boons of the program weren’t made accessible for everyone. As recounted by writer Luke T. Baker for the magazine Dirty Furniture, “Some states segregated Black and Indigenous people or even excluded them from the programme.”

Black people harvesting cotton to nourish an empire? Completely fine. Black people fashioning cotton to nourish themselves? Less so.

Since the country’s founding, cotton has been recruited to make so much evasive for Black people, from our rest to our humanity. Black folks are now left with something tense and ugly and marred between many of us and cotton in the wake of the plant’s exploitative, nation-birthing harvest. But this bond between us and cotton wasn’t always corroded, was never supposed to be a site of desecration.

A few weeks ago, I was reminded of Toni Morrison’s insistence that ghosts don’t have to be considered vicious, harm-hungry figures. For her, ghosts and hauntings can be practical, even pleasant.

I think of ghosts and haunting as just being alert. If you’re really alert, then you see the life that exists beyond the life that is on top. It’s not spooky necessarily—might be—but it doesn’t have to be. It’s something I relish rather than run from.

What if a haunting is a tool for better bearing witness to the density of histories—especially those that we’d rather forget, that institutions systemically invisibilize and substitute with their own myth-making—that accumulate in every corner of our planet? What if a haunting-as-technology can equip us to be more accurate and critical truth-tellers, to be more attuned to the fullness of our reality? I think of writer and gardener Jamaica Kincaid re-membering the beauty of cotton’s flower as a moment of encountering ghosts that facilitate a kind of recovery, repair, and resistance to the violence of erasure.

In “The Glasshouse,” an essay in the back half of her work My Garden (Book):, Jamaica visits Kew Gardens, an English botanical collection. Amid her roving, a corona of yellow beckons her. “[I]t was a most beautiful yellow, a clear yellow, as if it, the color yellow, were just born, delicate, at the very beginning of its history as ‘yellow.’”1 Jamaica assumes she’s in the presence of a hollyhock but, upon reading the identifying label, is shocked to discover the enchanting bloom is something else entirely: “It was not a hollyhock at all but Gossypium, and its common name is cotton.”2 Sent “a-whir” by cotton’s unexpected allure, Jamaica considers how the legacy of empire-building has robbed cotton’s world of its depth and dimensionality, rendering it small, incomplete, and soiled. “Cotton all by itself exists in perfection, with malice toward none; in the sharp, swift, even brutal dismissive words of the botanist Oak Ames, it is reduced to an economic annual, but the tormented, malevolent role it has played in my ancestral history is not forgotten by me.”3

In Jamaica’s world, ghosts that inhabit our lineages widen the aperture of myopic narratives and navigate us to the “perfection” beneath the sedimentation of “malice.”

Poet and essayist Anne Boyer, in a missive for their newsletter, writes, “A better part of being a gardener, too, is that plants don’t care who you are. A more disappointing part of being a person is a world that does, rather than allowing each to exist loved and cared for as a generally existing being generally existing.” More and more, I’m attempting to return to the prologue of cotton’s story, before the etching of its messy, fraught middle, to become reacquainted with its liberating medicine, its life-sustaining fibers, its inherent loveliness. While I’ll never be able to opt out of the legacy of what came before This Moment and These Times, I can still become friends with ghosts, making kin and allying with all who have been forged in the house white supremacy and capitalism built.

In recognition of oppressive powers shoehorning cotton into bolstering the colonial project of the United States, the plant was once thought of as being “King.” Of course those powers lacked the imagination needed to be in awe of cotton for a reason beyond its ability to be gruesomely converted into a source of incredible wealth.

For this month’s Broadcast, I’m reaching for those more imaginative, expansive reads of cotton with Dr. Ra Malika Imhotep.

Ra (Ra/They/Them) is a Black feminist writer, performance artist, and cultural worker from Atlanta, GA. They received their Ph.D. in African Diaspora Studies and New Media Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, and are currently an Assistant Professor of International/Global African Diaspora Studies at Spelman College. Their work looks at the ways Black feminine figures across the African diaspora subvert preconceived notions about black womanhood, black femininity, and labor through aesthetic practice. They are the proud chile of D. Makeda Johnson and Akbar Imhotep.

In this missive, Ra and I consider cotton as an accomplice in providing reproductive autonomy, the capaciousness of the plant and other maligned entities, and cotton as a trickster figure. I hope this conversation hits as hard for you as it has for me. (This conversation took place in March 2024 and has been edited for clarity.)

A Note of Acknowledgement: Throughout this conversation, Ra and I make several references to the work and life of Alice Walker. In the wake of the continued onslaught of violence against our trans and gender-nonconforming kin—of which Black trans women are made to be the most vulnerable—we acknowledge the impact of Alice’s recent statements questioning the criticisms of J. K. Rowling’s transphobia and her continued engagements with and willingness to learn more about transness and trans youth. As we excavate the medicine that lies within this literary elder’s canon, moving opposite of a culture of disposability, we, to borrow from Alexis Pauline Gumbs, “pray for her transformation and reparative action” and remain steadfast in our commitment to Black, queer, and TGNC communities.

Amirio: I want to start with this idea of origins because I feel like that's going to be a through line throughout this conversation. I was going through your work and I was led to the introduction that you wrote for a set of poems that you published with Scalawag. In the introduction, you wrote:

I’ve been noticing I hold a lot of my Southernness in my mouth. It’s my accent. It’s flavor. It’s the sweet. It’s the stank.

I love this idea of one’s origins and geography being embodied in such a rich, beautiful way. When we talk about this idea of the South, it feels so mythic. And people have so many associations with the South: so much imagery comes up, and there are so many variations of what the South is. What’s the South that you’re from? Can you describe it? And beyond your mouth, where does it live in you?

Ra: Yeah, that’s beautiful. In the work Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo by Ntozake Shange, the character Indigo is the youngest child and she’s eccentric. Reading the novel with contemporary language, I would call her neurodivergent, in the most beautiful way. She carries around these dolls, she lives in her own world. She writes up these recipes, and Ntozake writes that she “got too much South in her.”4 The South in her is what makes her this kind of magical realist being. Magical realism isn’t just the style of the writing in the book, but it’s literally how this girlchild lives. And I feel something akin to that.

Something I’ve thought for a while is that contemporary writings and books about the South are often narrating these rough encounters with the truth of the South. And I think I try to write from a place of there's too much South in my body at a cellular level—but what is “too much”? There’s an excessive amount of South in my body that is my proximity to my ancestors. It’s my connection to my ancestors, it’s the homegrown practices of ancestral veneration. So in that way, Southerness is in my spirit. It’s in my mind.

There’s a line from my poetry collection gossypiin where I write, “I am more imagination / than blood.” The impetus for me needing to write something like that down was needing to share a story about my origins that is real to me. And I recognize that act as magical realism, but it’s real to me. And some people are like, Wow, you have such a vivid imagination. And I’m often like, I had never thought of it as being imaginative. I thought of it as the circumstances of my birth; it wasn’t make-believe.

I had the privilege of seeing André 3000 perform New Blue Sun in Atlanta. One of the things he said, which was very similar to the stuff I was writing about and referencing in that Scalawag piece about why the South is in my mouth, was, “Yeah, I live in L.A. My language has gotten a little proper.” I could still hear the Atlanta in him, but sure. But he was like, “Yeah, I’m here. I started to notice my words getting a little round. I’m dropping certain things.” And I was like, That’s exactly it. That's where the South lives—in my mouth. I’ve gone to grad school; I went to college in Boston. I got my Ph.D. at UC Berkeley, and I carried that South with me everywhere. There’s a visceral impact of being home that shifts my orientation to language. It’s not just about how I use language: it’s about how my mouth forms words.

The last location of where my South is—well, there’s so many locations! One that’s particularly relevant to gossypiin—and I need to find spiritual language for this—is my womb, in that center area of my body, what they refer to in traditional Chinese medicine as the “lower dantian,” which is often seen as the root of the tree of life. I think I carry the South there, especially as I learn about histories of enslaved women’s reproductive resistance. The question that really opened up the project of gossypiin came from Marvin K. White, this phenomenal preacher, poet, queer radical, house and disco enthusiast—just everything! Marvin was in the Bay Area at this grief ceremony and was like, I wonder if there was a way that our ancestors who were experiencing sexual violence just shut their bodies down. And if they were able to do that, that would be more of that magical realist, Southern, intergenerational stuff that manifests in my body—which I framed at one point as reproductive dysfunction. But now, I think about it more as bodies moving otherwise towards and against the impossibility of proper “womanhood.” So I think I hold the South there in my dantian.

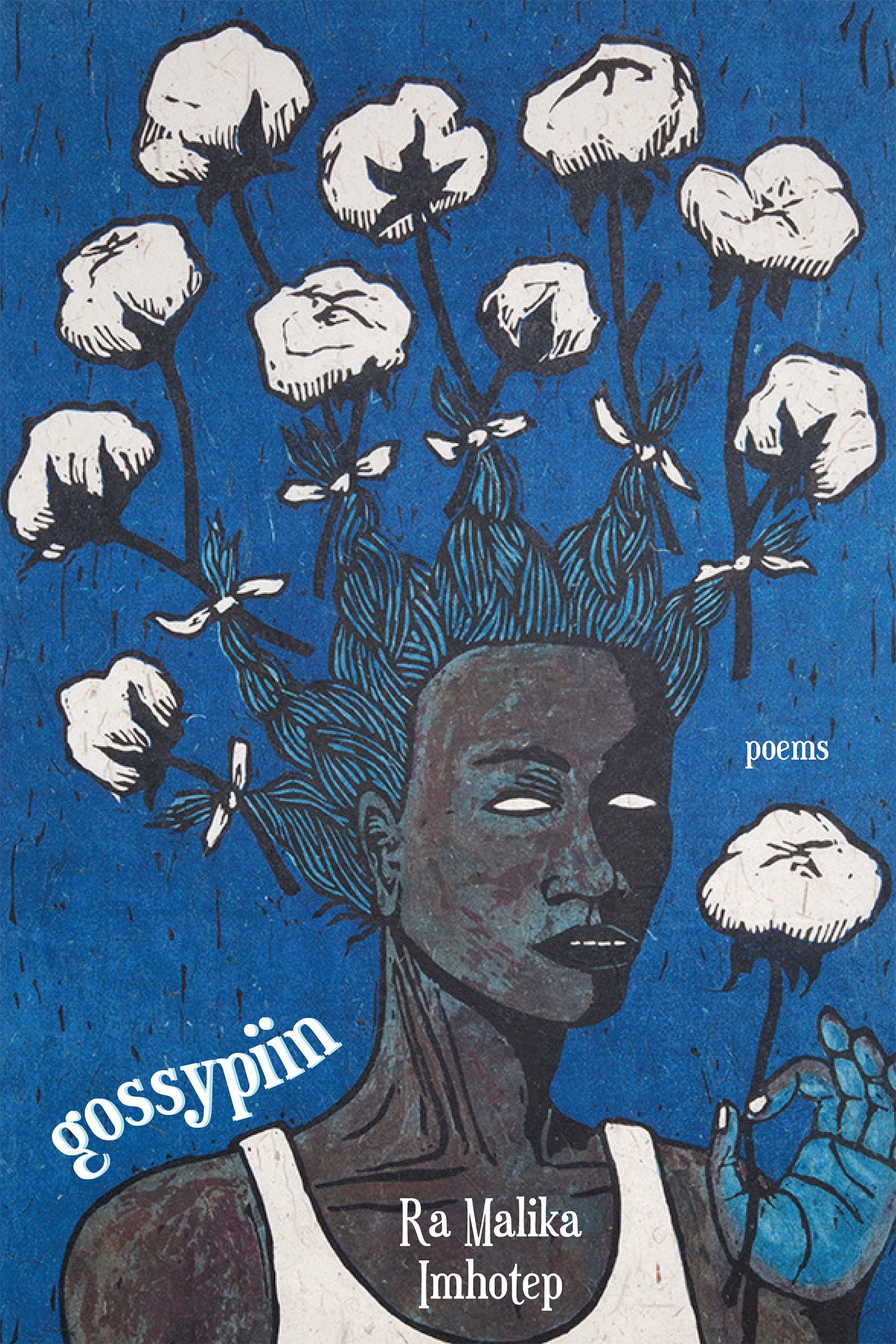

Amirio: You mentioned gossypiin, which is your poetry collection that I came to know your work through. I remember being so excited about reading it because the cover instantly grabbed my attention. The artwork is so gorgeous and beautiful, and what struck me immediately is the deep intimacy between this black feminine figure and the cotton plant. As we know, that’s a plant with a hauntedness, as you’ve referenced in past interviews.5 There are so many haints attached to it. So, by seeing cotton attached to this human in a way that feels so loving and intimate and delicate and tender, I was instantly intrigued. And then when you dive into gossypiin, there’s that tenderness and everything else mixed up with so many themes: lineages of black feminine figures, acknowledgment of present absences, bodily dispossession and wreckage through sexual violence, bodily resistance and autonomy through plant allyship and fugitive Black knowledge exchange. And I love how the cotton plant is at the center of all of that. How did you come to these other associations and relationships with cotton, and how did the plant end up helping midwife the poetry collection?

Ra: That’s such a perfect use of language because throughout history, it was the midwives possessing the knowledge that the root of the cotton plant is an emmenagogue, which is something that can stimulate blood flow from the uterus, and an abortifacient.6

I recently watched this film called Birthing a Nation: The Resistance of Mary Gaffney, which uses testimonies and slave narratives captured after Emancipation through one of those Works Progress Administration programs. In the film, and I forget the woman’s name—I want to say her first name was Mary. The point is that Mary talks about how she did not want to be a “breeder,” but her master gave her this husband and she was not feeling it. The master never understood why she wasn’t pregnant, but she was like, I kept chewing that cotton root.7 And that was the first time I had heard that story voiced outside of a book. I had done my research and I knew my things, but that was the first time I had heard that story out loud, centered in a film, pulled directly from a slave narrative.

As far as my entry point to the cotton plant, my father’s from Middle Georgia. My mother is ancestrally from North Georgia; she was a Great-Migration-to-New-York child but then returned to the South. But my dad was from Middle Georgia and grew up playing on what used to be cotton fields. The cotton field was a principal figure in his life, throughout his adolescence. So I already had that connection to cotton. I didn’t have any feelings of, Oh, this is a scary thing. Of course I knew of the blood, of course I knew slavery was bad, but there was always an intimacy with the plant. My father’s name is Akbar Imhotep; it feels important to say his name because he’s an ancestor now. He picked cotton and his sister helped him. They were sharecropping in a horribly violent system and yet, still, there were these moments of care and intimacy around this plant. So that’s the familial connection.

The other connection is that I was in the Bay Area working through trying to bring harmony to my body before I had language around disability and disability justice. I was taking all these herbalism classes during 2017-2019, and one I took was at a place called Ancestral Apothecary. The class was for women-identified people to get in touch with their ancestral medicines. So we’re doing a lot of the basic stuff, learning how to make tinctures, teas, salves, and balms. And this is happening around the same time-space that Marvin K. White is asking me that question: How did our ancestors shut their bodies down? And so I’m in this class, they’re asking me to identify an ancestral plant, and at first I’m like, Magnolia trees? But then I’m thinking, What are the main medicinal ancestral plants of my people? And then I got this book called Hoodoo Medicine: Gullah Herbal Remedies by a writer named Faith Mitchell, and I’m flipping through and it’s focused on the healing pathways of the people of the Georgia Sea Islands, the Gullah Geechee. I’m flipping and here comes the cotton plant. And Faith says, as I note in the epigraph of my book, that the French credited the midwives of the South—the Black, enslaved midwives—with discovering cotton’s medicinal properties. And she notes that the active component that provides cotton’s medicine was called “gossypiin.”8

Before there was even an idea of a poetry book, I’m encountering this history and it has a visceral impact on me. I’m thinking not only about ancestors and the cotton plant but also about reproductive agency. I’m thinking about Black women who chose not to bring more babies into slavery; I’m thinking about Black women who reclaimed their bodies through an alternative extraction of the cotton plant. When you go for the root, right, you remove the plant from the ground; the plant then is no longer a fruiting plant. And then you take that root and you use it as medicine. That is such a delicate process, especially compared to the kind of rough, finger-pricking cotton picking that we’re familiar with and that we associate with the horrors of enslavement.

So, at the time, I was holding all these histories: my brain hadn’t connected my familial intimacy with cotton—with the stories of my father’s life in Middle Georgia, in Houston County. I was just trying to do the herbalist thing, and I re-encountered the plant, smack dab. I remember when I had to tell my story about my ancestral plant during the herbalism class, I was so emotional. I was crying because it was just like, one, What a blessing to have this tool, and then, How do the acts and choices made using cotton’s root live in my body now?

Amirio: While reading gossypiin and doing research on the medicine of cotton’s roots, it was moving thinking about the genius and care it took to get that medicine—and to preserve the knowledge of that medicine across place and time. And it’s profound that the use of cotton by Black women who were enslaved is maybe one of the earliest examples that we have of striking, especially when considering that their reproductive capacity was linked to a broader economic system. There are many beautiful things we could untangle regarding the plant, but one thing I want to dig into is this tension that the cotton plant holds.

The plant represents so much beauty, especially in the way that you’re talking about, but obviously there’s this whole other attached history of brutality. That strain between beauty and brutality made me think about something you wrote for your newsletter in a recent missive about sickness. At one point you write:

When i type out “ache” its soundlooks like “axé” the Yoruba-derived invocation: “So be it.” but it be so much more. Axé be a whole philosophy of being. Be life-force pressed into each being (human, no-human, animate, inanimate) by the kiss of Oludumare. Nothing exists without Axé. Nothing moves without ache.

Now feels like the perfect time to bring in a few Black feminist figures that leading up to this conversation you were excited to bring in, particularly Alice Walker and Gloria Naylor. Especially with Alice, there’s that tension between ache and axé, beauty and brutality in her work. I immediately thought of “The Flowers,” a short story about a young, Black child, Myop, living in a sharecropping household. She's out walking around, outside of her home, and she’s noting all the beauty—of the water, the air, the trees—and then stumbles upon a brutal scene: the remains of a lynching. And when this character discovers the site, Alice writes:

Myop gazed around the spot with interest. Very near where she’d stepped into the head was a wild pink rose. As she picked it to add to her bundle she noticed a raised mound, a ring, around the rose’s root. It was the rotted remains of a noose, a bit of shredding plowline, now blending benignly into the soil. Around an overhanging limb of a great spreading oak clung another piece.

Especially when thinking about cotton, how do you hold that tension—again, between ache and axé, beauty and brutality—and how do Black feminist thinkers and writers help you navigate through it?

Ra: Yeah, I love that so much. I was so grateful when you reminded me of that short story. I was up in the middle of the night, and I was like, I need to read it right now. But then I was like, Go to sleep. You know that story, and you’ve been gifted the synopsis. But in the quote that you read, the ache is in the landscape and there’s no way to avoid it. It almost reminds me of the discourse around positive and negative images—and that is a reference to another Black feminist, Michele Wallace, who is the daughter of recent ancestor and Black feminist artist and organizer Faith Ringgold.

What choice do I have but to be friendly with spirit when the land I walk on is full of blood? Slavery—the brutality of work in the cotton field, in the tobacco field, and in the sugarcane field is often used to justify, even just colloquially, the distance that Black people have from the Earth. I ain’t trying to do no farming, I ain’t trying to do no hard labor because slavery. And I think that for me, just as I think about disability and think about the ache as something to live alongside, I know that legacy is my family’s history. The plantation where my ancestors were brutalized and enslaved in Houston County, in Middle Georgia, was the same place my father played as a child. Those people, those stories, those aches, those cries didn’t leave the land, but they still held space for him and his kin to play and to experience levity and to experience different modes of intimacy.

And I know that this don’t work for everybody. I’ve had to reckon with the fact that my positive obsession with the cotton plant is not normal for a lot of people. (laughs) People are like, Why is that image on the cover of gossypiin? I knew I wanted that art very early on. Shout out to Alison Saar for granting me permission to use it. Even on the mood board, I was like, That’s one of the ones. And at first my white publisher was like, I don’t know if I can sell it. And then we got confirmation from somebody else and it was like, Yeah, we can sell it. And I was like, Of course you can sell it because it’s stunning work by a major contemporary artist. What are you talking about? With the cover, the ache and axé is there, too: the cotton is adorning this girlchild, but it’s also giving this kind of re-imagined Topsy-type figure.

Topsy is often understood as a harmful stereotype-trope of the Black girlchild from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, on the minstrel stage across the world. In my academic work, I think a lot with her. There’s a scholar named Jayna Brown who writes that when performed by white women in minstrel acts, Topsy allowed those white women to access these freedoms that they otherwise wouldn’t have been allowed. And they were exercising their control over Black women’s bodies. But when Black women got to play that role, or when Black women got to embody a Topsy-esque energy—we can think about images of Josephine Baker with her eyes crossed, we can think about Ida Forsyne who, even though she never played Topsy, was billed as Topsy when she traveled abroad because she was small, dark-skinned, and a performer—there is a resistance history of Black women’s embodiment of that immortal, creative wildness. So, again, the ache and the axé—how the minstrel character is both the pain, the stereotype, the limitation, and the portal towards life otherwise. For me that’s really deep.

The whole Lil Cotton Flower9 thing emerged alongside gossypiin and as a part of my performance practice. Whenever I put on red lipstick and look in the mirror, I see Topsy staring back at me. How do I reckon with that? I can’t escape that. So how do I live alongside it? I still don’t wear red lipstick quite often, but it’s not because I’m scared of Topsy looking back at me—it’s just not giving. The ache is what grew me, and the ache is what gave me my power.

Thinking about the quote that you read from “The Flowers,” the child’s encounter with the lynching doesn’t make the oak tree less awe-inspiring. The wild rose isn’t now dwarfed by the noose. Alice takes the care to still describe the natural elements around the tree, that surround the body—or surround the remnants of the corpse. That doesn’t mean that the child’s not traumatized: it means that nature is more capacious than these spectacular acts of violence. That the act of lynching was a gross abuse of our beautiful poplar trees, but the act didn’t make the poplar trees less beautiful and less worthy of our adoration and respect. Perhaps even more so because of what they too survived. They survived their own violation and exploitation. The poplar trees wasn’t trying to participate in those violent murders. Now I’m like, What? I’ve never thought about the trees that folks were lynched on in this way, but it’s really coming up for me. The oak trees and the poplar trees did not want to participate in that. They were exploited the same way our ancestors’ bodies were exploited. So that is a kinship that we can’t take for granted, or that I no longer will take for granted now that it’s come together for me.

Amirio: I want to keep going down this thread! Something I wrote down while you were speaking was “the capaciousness of the maligned.” Cotton has been maligned, but there’s a capaciousness that you’re bringing out of it. You brought up Topsy, and I’m thinking about these other figures that you're playing with, especially in gossypiin. You have poems where you’re giving voice and autonomy to the Mammy10 and Tar Baby11 figures. Even thinking about Lil Cotton Flower, I love how that character is a mix of maligned archetypes that you’re drawing so much from. Also, when thinking about the relationship between cotton and Black people—both maligned—I’m interested in how there’s an interspecies redress that’s possible in the rub between the two groups. I want to know where your interest in the maligned comes from.

Ra: I love the Maligned. I love the Black Maligned. Particularly because I don’t think we should let white folks steal stuff from us. Okay, this is a silly reference, but I’m like, Why should I be ashamed to eat watermelon? God has blessed me with this delicious fruit. I mean, it’s not everybody’s thing, but God has blessed me with this beautiful, enjoyable, water-full, sugar-full thing, but I’m not supposed to like it because some white people just saw that I liked it and then decided to make a caricature of it? No! We have to think about malignment as a process through which things become maligned as a function of white supremacy. For example, an unkempt Black girlchild shouldn’t be the embodiment of evil. But when Harriet Beecher Stowe is writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin and she’s like, Well, I have sweet Little Eva, I need an opposite for her—the opposite is an unkempt, dirty Black girlchild. But why accept that an unkempt, dirty Black girlchild is the worst thing to be? Is evil, is lesser than?

I am obsessed with the figure of the Tar Baby. I’ve been recently having opportunities to write about it more and more. This is, again, another kind of lineage transference between me and my father, who worked as a storyteller and first introduced me to the Uncle Remus tales—the Br’er Rabbit stories that the figure of the Tar Baby comes from. Those narratives are diasporic; in my storage unit, I just found this copy of Compère Lapin, a kind of Creole French derivative of Br’er Rabbit. That would’ve been how that character was known in the context of French New Orleans, whereas in Georgia, he’s Br’er Rabbit.

There’s this place called The Wren’s Nest in Atlanta, Georgia, in the West End, which is the historic home of Joel Chandler Harris, who is the person who, I say, transcribed the Uncle Remus tales, the Br’er Rabbit tales. Of course he took some creative liberties, but the story goes that he was in Eatonton, Georgia, the same birthplace as Alice Walker, and he was apprenticing on a plantation as a young kid and would spend his time in the slave quarters listening to stories. The Uncle Remus character of those stories is this avatar for enslaved, older Black male storytellers. But then Uncle Remus becomes a maligned character, even though in those tales he’s honorable.

Stepping back, I come to the Tar Baby through my father’s work, not only through listening to him tell the Br’er Rabbit stories over and over again, but also through seeing this little Tar Baby figure in The Wren’s Nest—which was just this little gummy sculpture thing—and loving it instinctually and being drawn in by it. By its little hat and its little nose and its roundness, and loving it and identifying with it. As a child, I identified with this little juicy Black thing as a little juicy Black thing myself. I’m going to be thinking about this for a while. There are ways that my embodiment as a queer, agender, dark-skinned Black person with natural hair—I would say nappy hair, and I know I got locs now, so it’s different—has been maligned throughout my lifetime. Particularly as a child. I got this eccentric, African name. It’s not even a name pulled from a specific continent. It’s a name pulled from my parents’ different investments in different parts of Pan-Africanism. It’s a real name, but I’m saying it is not a name where you’re like, Yes, that part of your name is Nigerian. It is like, Well, we like this name, we like that name, we like this name, and here go. And I love that. I’m growing to love that, but when I was younger I was like, I ain’t even doing the Pan-African thing right. So those are things that led me to live a maligned public life—different from the life in my household or within my community, where I did experience affirmation. But at school and in the world, I was always too dark or too this or too that. So that was the world of feeling I was in when I encountered this Tar Baby. So immediately, that figure is no longer maligned to me. I’m like, I love you, Tar Baby. I love you, Topsy. Because you represent me. I’m not thinking, on some Zora Neale Hurston shit, at that moment about how white people see us.

Lil Cotton Flower evolved from a project I wanted to do, and halfway did, called Slutty Slave Girl. I wanted to imagine what would happen if the same way on Halloween they make the Slutty Pocahontas and the Slutty Geisha and the Slutty Princess Jasmine costumes—what if there was a slave one? What if there was a Black one? And what happens if I walk around New York on Halloween in this kind of Black, slutty slave attire? Now, the first experiment kind of failed because there’s just a lot going on in New York; it didn’t create the disruption I wanted. But even that is a teaching: it wasn’t disruptive to see a Black femme walking around dressed like a slave in tattered white cotton. So Lil Cotton Flower grew out of that. And it was kind of like, Well, you don’t want your burlesque name to be Slutty Slave Girl, and you are into this gossypiin thing right now. And cotton flowers before it bolls and puffs. We don’t think about that. We don’t think about that period of the cotton plant’s growth where there are these blossoms. And so Lil Cotton Flower, again, is like a grasping—a holding close of not even just the Maligned but the Overlooked. Which is also my point with the Tar Baby. I’m like, This is an overlooked character. We think of this character as just a means to an end, an instrument used in the long arc of Br’er Rabbit’s trickery. But what if we just stick with her, with them, with their Black, feminized presence? What do we learn from that? What if they’re not just a means to an end?

Toni Morrison has a novel called Tar Baby. When I first read it, I completely missed that it’s basically a retelling of a Br’er Rabbit story. I was like, What? In this The New Republic interview called “The Language Must Not Sweat,” she’s talking about how tar was a sacred thing, and she’s like, I don’t remember the African thing where I’m pulling from, but I know that a tar pit used to be sacred. And so I think about the Tar Baby as the Black woman who holds it all together.12 And that for me is the foundational moment where I was affirmed in my reclamation of the Maligned. And then of course, rhetorically, a “tar baby” is a problem you can’t get out of, an inescapable problem, which I think is interesting. The Black woman holding it all together is also an inescapable problem for imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy, as bell hooks put it.

Another kind of interlocutor for this reclaiming of the Maligned for me is L. H. Stallings, an academic with a capacious mind. They have a book called Funk the Erotic: Transaesthetics and Black Sexual Cultures. Their first book is called Mutha’ Is Half a Word: Intersections of Folklore, Vernacular, Myth, and Queerness in Black Female Culture, and it’s about Black women in vernacular culture and all the ways that Black women comedians and other cultural producers embody these maligned tropes. So I love that you’ve gifted me this language of an investment in the Maligned or an investment in holding the Maligned, sticking with the Maligned, because I hadn’t thought about it that way. But I do think I’m in a tradition of folks who do that. And in a tradition of folks who’ve been maligned: Zora Neale Hurston is one, Alice Walker is another. And I’m not saying that to dismiss the more recent critiques of Alice around the statements that she’s made around trans children. But I think in general, even before that, when she wrote The Color Purple, off the bat, people were saying ugly and atrocious things. As a caveat, I do know for real that Alice Walker is having conversations and is interested in more consciousness-expanding dialogues about trans life. I know that for a fact, and I’ve had to realize I don’t have to protect these women; they’re good. And they’ve lived the life of the Maligned—maligned both by nature of being Black and born into these feminine-marked bodies, these female-marked bodies, period. And by daring to challenge imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

Amirio: I want to keep talking about cotton by situating it in a trickster archetype lineage. I love how plants offer us this idea of opacity. With cotton, this plant has medicine—but it’s medicine available in a subterranean, less-upfront way. With plants in general, there are these questions of, Am I mobile or immobile? Am I an animal, or am I not an animal—especially as it relates to carnivorous plants. There’s opacity there that is so interesting and beautiful and fucks us up. That opacity mirrors how you’re a trickster, too, in a lot of ways—especially when moving against these white supremacist, rigid categories that we try to impose on ourselves and more-than-human life.

Ra: Well, first and foremost, I love thinking of cotton as a trickster. You have changed my brain and I will never not think of cotton as a trickster plant again. Second, when I was in that Ancestral Apothecary class, we were talking about roses—how for most of its life, a rose is a thorny bush and then has these moments of blooming. It’s this thorny bush that at some point offers you beauty—and even that comes with the threat of pain if you don’t treat it right, if you don’t treat it with care. I think the question of opacity is another Zora Neale Hurston lesson: a refusal to translate. And a Toni Morrison lesson.

There was a moment in grad school where I was like, Cool, I want to write about the Black South. I want to write about Black feminine figures in and of the South. I want to write about Black culture in the South. What I’m not interested in is explaining things to white people, making things legible to white people. Early in grad school, I wrote a paper about Twerk Team. It was the most liberating exercise ever. And I remember some feedback I got was like, Well, can you define this? And I don’t think the word “twerk” needed defining, but it was something that you wouldn’t need to define for a Black audience. And I was like, No, I don’t wanna do that. That’s actually not the labor that I want my work to do.

Amirio: This isn’t an episode of black-ish!

Ra: We’re not doing it! And if that is the mandate for what it means to produce academic work—absolutely not! And I’m grateful for models that I have like L. H. Stallings, like Fred Moten. And there’s people like Gloria Naylor, Toni Morrison, who are able to de-center the white world whilst telling full stories about Black life. Earlier you mentioned planthood as a method, as a lifeway—observing plants as a guide for how to live. And that was something that was really sparking up for me when I lived in Oakland. I have a beloved named brontë velez—

Amirio: We love Lead to Life!

Ra: Exactly! Their work involves spiritual ecology, which takes permaculture to another level. It’s about reclaiming my spiritual relationship with the Earth. For me, that is a return to an African cosmological ordering of things. I think we are meant to live in harmony with the Earth, to follow the Earth’s ways. And now that’s increasingly hard as the accumulation of power is draining all the lifeblood out of this planet.

In fact, in the conversation I was blessed to have with Alice Walker and one of my Berkeley professors, Darieck Scott, I asked Alice something about the future, and she was like, Do we have a future? Her point was like, When I was growing up, stuff was hard, but we had the Earth. We had fruiting trees all around us. We had expanses of land to relate to and to play in. And we don’t have that right now. So what does the future look like for us? And so I think that the work you’re doing is so important because it’s inviting us to reimagine who these plant beings are around us. To return to Alice Walker, I think it pisses God off as you walk past the color purple and not notice it. What does it mean to really be attentive to the natural world around us? Not as just something ornate, but as something that can teach us something, that can nourish us. I’ve had many conversations with people who are like, Yo, you could eat fruit right off the tree? If you walk past a lemon tree, you could eat it? And it’s like, Yeah, you could eat a fig off a tree! And I think that we have to repair that. Like I was saying at the beginning, I feel like histories of enslavement, sharecropping, and even the Great Migration—this need to leave the South, to leave agricultural labor, towards industrial labor—have created these really deep chasms between Black folks and the land and all that we are naturally blessed with. And I’m like, We better get in right relation while we still have time.

If a plant can be a goddess, a plant can certainly be a trickster—and a plant can be a trickster goddess. And a plant can be a wrathful goddess. Maybe the rose is a wrathful goddess, and we can learn something about how to protect our hearts through deep study and apprenticeship to the rose. What will I learn? What have I been learning while studying and being in apprenticeship to cotton? I want to do that more. My plan, when I left grad school, was like, I want to go live on a farm for a whole planting cycle. I want to be an apprentice to some land. Now I took a non-landworking job, but I’m going to get there because it feels important in ways that you’re helping me remember and recommit to and re-understand.

Amirio: Well, whenever you start the Church of Cotton, I am ready to be a disciple! I’m in line for that. So let’s end here. And I want to end on Alice Walker. While preparing for this conversation, I watched her documentary, Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth. There’s a beautiful segment where she’s invoking this idea of eco-intimacy: she talks about how growing up she, her family, and her community always lived in nature, and trees were more familiar to them than people. Later on, she talks about how—and I’m paraphrasing—I left formal religion in favor of the forest. This is the only heaven I come for. Where in the more-than-human world do you find the heaven that you keep going back to again and again and again?

Ra: That’s such a beautiful question, and Imma tie a Gloria Naylor reference into it because it feels important.

Amirio: Bring her in, bring her in!

Ra: Mama Day, a novel in Gloria’s universe, is based on a magical realist, Georgia Sea Islands-type landscape. One of the things that you brought up in preparation for this conversation was how Naylor articulated the fact that she wasn’t estranged from the South.13 There’s this beautiful interview, or really conversation, between her and Toni Morrison where Gloria is sent to interview Toni, but then they end up just chopping it up as peers. And one of the things Gloria said was, “To write Mama Day, I had to go there. I had to walk the terra firma. I had to walk the Earth to receive the information that would shape the novel.” What I’m realizing more and more is that heaven on Earth for me is sweet water, like creeks and lakes, particularly as I’m dealing with disability and sickness and my nervous system going through all kinds of things. To hear the sound of water rushing, to feel water rushing into my chest, and even just to sit still and watch the water rush against the rocks—for me, that is a heaven on Earth. And also when I sit where salt and sweet water meet in the brackish, which is very much New Orleans, which is very much the Bay Area, and just look at the horizon and be with the water—that is heaven on Earth to me as well. Rushing water and where the sweet and the salt, the fresh and the ocean meet are sacred spaces for me.

Ra’s Recommended Resources

Podcasts

Books

Nikky Finney, Rice

Sebene Selassie, You Belong: A Call for Connection

Octavia Butler, Lilith’s Brood trilogy, Parable of the Sower

Malidoma Patrice Somé, The Healing Wisdom of Africa: Finding Life Purpose Through Nature, Ritual, and Community

Sobonfu Somé, The Spirit of Intimacy: Ancient Teachings in the Ways of Relationships

Rupa Marya and Raj Patel, Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice

Music

André 3000, New Blue Sun

Bernice Johnson Reagon, Give Your Hands to Struggle

Dorothy Norwood, Shake the Devil Off

Learn More About Ra’s Work

Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Book):, p. 149-150

Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Book):, p. 150

Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Book):, p. 150

Amirio: From the book (p.4): “Even her mama knew that, and she would shake her head the way folks do when they hear bad news, murmuring, ‘Something’s got hold to my child. I swear. She’s got too much South in her.’”

Amirio: From Ra’s The Poetry Project interview: “Socially and historically, predetermined or overdetermined, Black folks’ relationship to cotton is haunted because of the transatlantic slave trade. It became the oppressive plant…the thing we picked…a lot of people have aversions to this plant. Then you have people that think of it as a decorative plant, and that’s a whole other thing (laughs).”

Amirio: From Faith Mitchell’s Hoodoo Medicine: Gullah Herbal Remedies, as cited in the epigraph of gossypiin (p. 17): “Other Afro-American Use: ‘In 1840 a French writer, Bouchelle, reported that the root bark of cotton was widely used by Negro slaves in America to induce abortion. According to Johns U. Lloyd, ‘the credit for the discovery of its uses [as an abortifacient] must be given to the Negroes of the South.’”

Amirio: Gaffney in her own words, as shared in the journal article Resisting Reproduction: Reconsidering Slave Contraception in the Old South by Liese M. Perrin (p. 262): “Maser was going to raise him a lot more slaves, but still I cheated Maser, I never did have any slaves to grow and Maser he wondered what was the matter. I tell you son, I kept cotton roots and chewed them all the time but I was careful not to let Maser know or catch me.”

Amirio: Today, the substance is called gossypol. You can learn more in the journal article Resisting Reproduction: Reconsidering Slave Contraception in the Old South by Liese M. Perrin.

Amirio: As described in gossypiin (p. 21), Lil Cotton Flower is a “funky Black feminist fantasy.” Ra continues: “A character I inhabit on stage to ‘strip down layers of attenuated meaning.’ A sticky trickster-self that has emerged from the ‘marvels of my own inventiveness.’ In [the book] they have revealed themself to me as a playful presence with no investment in being respectable nor human.”

Amirio: “Mammy Councils Her Kin” (p. 81)

Amirio: “Lil Cotton Flower Tells a Story” (p. 77)

Amirio: From the interview Ra references: “In the book I’ve just completed, Tar Baby, I use that old story because, despite its funny, happy ending, it used to frighten me. The story has a tar baby in it which is used by a white man to catch a rabbit. ‘Tar baby’ is also a name, like nigger, that white people call black children, black girls, as I recall. Tar seemed to me to be an odd thing to be in a Western story, and I found that there is a tar lady in African mythology. I started thinking about tar. At one time, a tar pit was a holy place, at least an important place, because tar was used to build things. It came naturally out of the earth; it held together things like Moses’s little boat and the pyramids. For me, the tar baby came to mean the black woman who can hold things together. The story was a point of departure to history and prophecy. That’s what I mean by dusting off the myth, looking closely at it to see what it might conceal…”

Amirio: In an interview (p. 24), Gloria shares how she stayed connected to the South despite growing up in New York City: “I listened to [my family] tell stories. So I heard about the fishing and going to the woods and picking berries. And I heard about working in the cotton fields and about the various people, the different characters who were in Robinsonville… the women who worked with roots and herbs… the guy who ran the church… the man who was always drunk. A whole microcosm of people lived in that little hamlet.”

"What if a haunting is a tool for better bearing witness to the density of histories—especially those that we’d rather forget, that institutions systemically invisibilize and substitute with their own myth-making—that accumulate in every corner of our planet? What if a haunting-as-technology can equip us to be more accurate and critical truth-tellers, to be more attuned to the fullness of our reality?" Incredible questions. Thank you for this interview.