In James Bridle’s book Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence, we’re reminded of a fundamental truth, upending the enduring fiction of human supremacy: plants “precede us, and make life, everywhere, possible.”1 They continue: “[T]hrough photosynthesis, soil production and the conversion of nutrients into food, plants are the founders and sustainers of the world.” Bridle foregrounds that we were never the first to roam this planet and, thus, we owe a debt to all our Earth elders—especially our vegetal kin.

The world of plants begets our own. In that way, vegetal bodies are gestational bodies. And, yet, the centrality of plants in our daily lives is oft-obscured by all the ways we move plants to the periphery, to the bottom of our hierarchies, leaving them devoid of agency and bereft of interiority.

Plants as decor. Plants as things. Plants as Nature, far removed from the realms of Culture and the Human. Plants as akin to ambient music: a class of life that is “ignorable as it is interesting,” to borrow from musician Brian Eno. These are some of the perspectives and narratives—very Western perspectives and narratives—that have and continue to render plants passive and inactive and, thus, measurable, monetizable, and conquerable. Even Aristotle believed that every plant has a soul “capable of reproduction and growth, but is insensible and immobile.”2 Yet, the joke’s on us. Plants still rumble from the background, as they always have, communicating with each other, migrating to more suitable environments as the planet warms, and engaging in other acts that defy our expectations and understandings of plant life—and ourselves.

I wonder, then, what’s possible when we move plants back to the center, attuning our senses to witness them differently, listening to them with renewed intention, becoming literate in their language, and returning to being in full relationship with them. For Bridle, when plants speak, and we hear them, “the boundaries which we thought enclosed our worlds are shaken.”3 From such a world-unmaking convulsion, perhaps we could dissolve our fidelity to human-ness, opting to be more vegetal instead, with new commitments to make, new values to make homes of, and new mythologies to tell ourselves. After all, the anthropogenic reality we’re inhabiting now is wholly unworkable. As the unspooling violence of climate change brings into relief, a human-centric vision of the world is a death-centric one. What, then, could vegetal perspectives help us build from the rubble of human imagination? How can planthood be a method for living otherwise?

Those questions, and so many others, are at the root of this newsletter, PLANTCRAFT. I’m excited to have you here to explore them with me alongside guests I’m inspired by, starting with one of the most recognized and iconic plants of all time: the rose.

Since deep time, roses have “enhanced complexions, been used against plague, washed and purified the Mosque of Omar, and been incorporated in the preparation and burial of the dead.”4 The plant’s imagery is found everywhere, from religious scenes to fairytales like Beauty and the Beast to our emoji keyboards. Today, we gift each other roses to signify our devotion, and we watch with bated breath as the Bachelor(ette) du jour offers roses to their remaining suitors, all still vying to be the last one standing. The rose is omnipresent to the point of feeling like an abstraction or mere symbol, something suspended outside of time and space, versus an Earth-bound organism with its own sphere of life—full of friends and enemies, dramas and mundanities—to attend to. For this inaugural Broadcast, I attempt to facilitate new encounters with the rose, meeting it on new terms that defamiliarize and re-enliven it alongside this month’s guest, Kate Weiner.

Kate is a writer, editor, and community publisher. In collaboration with Kailea Loften, she is the Co-Editor of Loam, the publishing branch of Weaving Earth, as well as the Director of Loam Library, a mobile library and reading room that brings the power of print to the people. Kate is a 2018 Spiritual Ecology Fellow, a 2021 Activist-in-Residence at Boulder Public Library, and a 2023 Editorial Fellow at the Center for Humans and Nature.

Together, Kate and I dive into the profound ways roses show up in our ecosystems, the capture of rose medicine by beauty culture, how roses can help us enact “sentience justice,” and so much more. I hope you’ll get back to me with your thoughts—and share this conversation with anyone who might enjoy it. (This conversation took place in December 2023 and has been edited for clarity.)

Amirio: How did roses initially come into your purview? How were they first introduced to you?

Kate: I've always been passionate about flowers. As a kid, I spent so much time biking through my New York suburb snapping Polaroids of different ones. They were beautiful, communicative, and colorful. I just loved them! When I started gardening in high school, I forged a new relationship with flowers through the lens of edible blooms, such as calendula, borage, and nasturtium.

But for a long time, I wrote off roses, in part because of their ubiquity and in part because so many of the roses that I was introduced to were either the scentless varieties that you can find in almost any grocery store5 or the manicured roses that grow in “formal” gardens. Those roses didn't speak to me. They weren’t lush or wild—which is what drew me to flowers as a child.

In the last few years, as I've deepened my herbalism practice, I've realized how much I've lost in rejecting the gifts of the rose. Because roses are so popular, I thought I knew their story. But throughout history, roses have had incredible ecological and symbolic significance worldwide, particularly in the SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African) region. They're profound communicators within their ecosystem and sensuous allies for heart healing and growth.

And so, I've come back home to roses as part of a juicier longing to really listen to the plants that I’m in conversation with. I want to learn what they have to share independent of the limiting heuristics that I've developed to navigate the world.

Amirio: I'm now thinking about Professor Tara Mulder, who talks about how roses signify so much, including “religious devotion, erotic desire, and luxury.” We could have a whole separate conversation about the rose as symbol, but first, I want to center the rose as an autonomous life form with its own preoccupations. I want to foreground the plant-ness of the rose. Can you talk about the rose as organism?

Kate: As an organism, we can define the rose as a flowering shrub. It's a member of the Rosaceae family, which includes hawthorns, almonds, and apricots. I want to say, however, that the Linnaean classification system has real limitations; how we conceptualize roses in Western culture is shaped by racist, colonial, and supremacist systems of thinking.6 I always want to foreground that when we talk about who the rose is related to—because we could think of roses as being in relation to a lot of different plants, in a lot of different ways.

In terms of the plant-ness of a rose, we can break down a rose into three significant parts: its flower, its fruit, and its stem. The flower of the rose has lush, soft petals. The fruit of the rose, the rose hip, is a juicy source of Vitamin C. And the stem of the rose has distinct thorns. These thorns are not only a way that a rose survives in its ecosystem, but also a material embodiment of the rose’s spiritual significance.

It's important to note that the rose is vulnerable to climate change: the conditions that it needs to flourish are profoundly incompatible with a much hotter, drier world. So this flower that has been part of many cultures for many years is at dramatic risk at this moment. And that’s significant because roses are some of the oldest flowers that we have evidence of. There are fossilized blooms that go back over 50 million years.

Amirio: I want to go back to this idea of classification—I'm so glad you brought that up. We can think about roses and other plants through a Linnaean framework, but that system erases and invisibilizes alternative ways of thinking about roses, especially regarding relationality.

I'm thinking about, for example, the Lil̓wat7úl (Lil'wat) Nation—an Indigenous community in Northwestern North America that has cultivated a revered basket-weaving tradition. For this community, when the Nootka Wild Rose (Rosa nutkana) and Prickly Wild Rose (Rosa acicularis) bloom, it's a signal to the community that the vegetal materials needed to make their baskets are also abundant, available, and ready to harvest. Roses act as phenological indicators that situate people in relationship with the more-than-human world.

I want to continue thinking about the rose but in terms of medicine. You brought up the physical composition of this plant, and it's been astonishing reading about how its different parts offer so much medicine that's been used across centuries. Rose water was used amid the spread of the Black Death for sanitation and treatment; there's gynecological literature documenting how roses were recruited to address vaginal ulcers, uterine hemorrhage, and more. Even today, there's a massive industry driven by using roses to achieve a more radiant complexion. Can you talk about how rose medicine has been used historically and to this day? And how do you use it in your day-to-day?

Kate: Historically, rose medicine has been considered a heart-opener and healer that can cool inflammation, tone lax tissue, and help us feel more grounded in ourselves. There's this gorgeous cookbook, Parwana: Recipes and Stories from an Afghan Kitchen, that includes several luscious recipes for healing Afghan rose syrups and sweets that are meant to not only soothe “heat,” or inflammation, in the body but also delight the senses. In India, there's a long history of the rose as medicine: it's used to cool the body during hot, humid days.7 And in folkloric herbal traditions from Mexico to Morocco, rose is woven into foods to foster ease and boost flavor.

I love rose petals in tea, particularly with nettle, marshmallow root, and tulsi: nettles are very nutritive, mucilaginous marshmallow root is good for digestion, and tulsi is incredible at easing anxiety. Rose-infused tea is great medicine for when you're experiencing heartache and you need to help your “hot” loneliness and ache flow through the body. If a friend tells me they want a tea for sitting with tenderness, I always think of rose petals as a way to help them get back into their sensual self.

I also love rose petals scattered into a respiratory steam, especially during wildfire season. Respiratory steams are incredible medicine for sustaining our lung health when it's smokey outside, and rose—in partnership with aromatic herbs such as thyme—can lovingly help us release.

Rose hips—the juicy, red fruit of the rose—are some of my absolute favorites. They're super rich in vitamin C and good for immunity. In Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask, author Mary Siisip Geniusz talks about the importance of collecting rose hips for our community to nourish each other through the cold winter. That’s part of the medicine of rose hips: they provide healing for those we're in community with. They’re a way for us to care for one another and ensure that our immune systems are strong and stable throughout the colder, wetter months.

I also love rose hip-infused oil for the skin. As our largest organ, our skin needs extra good care, and the Vitamin C in rose hips is particularly supportive for connective tissue.

Amirio: I love this idea of casting different plant kin as our allies, especially as we confront these moments and systems that are death-driven and not at all life-affirming. At this moment when we're experiencing the consequences of a warming planet (e.g., heat waves), rose medicine feels relevant, especially given rose’s capacity to be a cooling medicinal plant. I’m also resonating with roses providing heart and community medicine, given the times that we're facing right now—with what's happening with our Gazan siblings and other communities worldwide. Knowing that we’re still witnessing COVID, it’s profound that roses are also immunity-boosters. Rose medicine is something we should be tapping into more. What are your thoughts on the power of roses amid the times we're in?

Kate: I've been thinking a lot recently about something somatic counselor tayla shanaye wrote in the newest iteration of her book Nourishing the Nervous System on how being with the body—with the life-affirming, the material, the sensual—can help us counter death-making systems. What does it mean to continue to show up in embodied solidarity for one another? How do we move from a place of collective care—true collective care—and real, felt solidarity?

Rose medicine is good for building solidarity because it is skilled at helping us come to a place where we move with possibility. We see how sick these systems are and how profoundly necessary it is to transform them. We are able to recognize and feel that we are in this moment of collapse—and I think that's the gift of rose medicine. This moment is one we need to be feeling. We need to have our sentience; we need to have our humanity. I've been thinking about how systems of oppression dehumanize everyone: they dehumanize the oppressor and the oppressed. And that doesn't mean that the experience is equal or equitable for both groups—far from it. I share that to say that we're in a moment when we've been made less human by the systems that shape our world, and rose can help us be more human with each other.

Amirio: The rose has all these associations with the senses. The way it smells. It's associated with lustiness, eroticism, desire, passion, and heat. Roses reify the importance of tapping into the senses, having sentience, being embodied in the world, and being connected. Can you talk about why we all should have access to sentience—and how the rose helps us tap into that?

Kate: David Abram has an essay that speaks to the sensorial wounds incurred through living in this era of ecological emergency. For those of us who have computer jobs, class privilege, and/or time privilege, we can numb our senses. We can continue to make our world smaller and smaller so that we don’t have to feel the sensorial wounds of living in a world that has been so devastated by colonialism, capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy. But as lawyer and climate justice organizer Colette Pichon Battle says, “If you don’t cry deep, hard tears for the state of this planet and all of the people on it, you don’t yet understand the problem.” It’s important to be able to feel our grief and not numb ourselves. It’s important to be in the wholehearted, full-bodied ache of what we're losing, of what we're doing to ourselves, and to our Earth. Rose medicine is a potent tool for helping us get to a place where we can be supported in feeling the wholeness of our grief. Because if we can’t feel our grief, we also can’t feel our love. And it’s our capacity to come into contact with our full range of emotions—our sentience—that helps us return home to the sensorial world as an expansive, complicated, painful, beautiful, heartbreaking, possibility-rich place.

Amirio: Today, it seems we need to enact a call for sentience justice. These systems take away sensorial experiences that connect us to something bigger, more imaginative, more creative, and more just. The eradication of sentience seems like another weapon that these governments and war machines use.

Kate: I love this term sentience justice. A part of the reason why we’ve been able to rob people of experiencing roses—as a metaphor for poetry, for music, for art—is because we've feminized the rose. We've made beauty and what the rose stands for feel superfluous, superficial, and supplemental. Because of that, we live in a world that denies people their right to roses. People need roses in their day-to-day, metaphorically and literally, in order to live full lives.

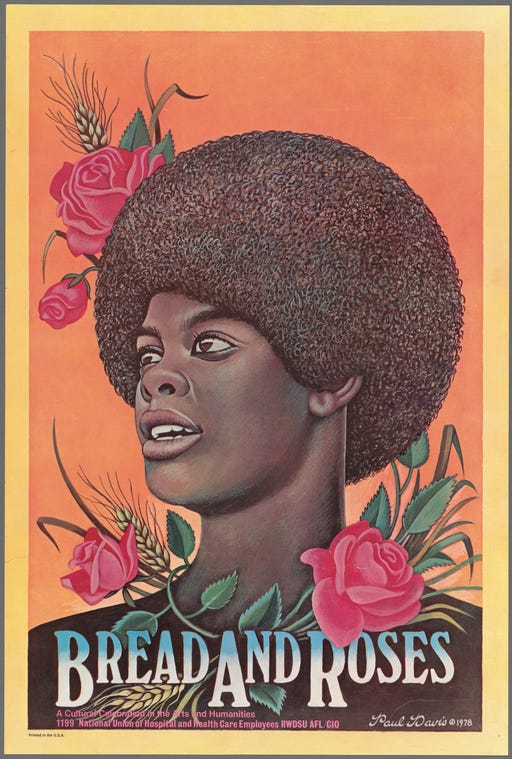

Amirio: In preparation for this conversation, you brought up the “Bread and Roses” slogan, which various movements, including the labor movement, have used. The slogan speaks partly to this idea that people need access to sentience and life’s roses. I’m also thinking about how flowers are oft-considered passively feminine and devoid of strength and hardiness. But I see all things representing femininity, including roses, as having an innate ferocity that upends how we're used to seeing power represented.

Kate: I think that slogan has had such resonance for so long because “bread” speaks to our need for a home, a foundation, and stability—things everyone has a right to. But it's not enough to have a job that pays us well and a place to stay at night: we need “roses.” And roses represent what makes life juicy, sensual, and pleasurable—things that shouldn’t be optional. It's bread and roses, not bread or roses.

In terms of what you shared about the femininity of roses, I've often thought about how it's possible to rub a rose petal in your hand and tear it apart, but if you watch a rose garden in the rain, the flowers mostly stay strong; they can withstand the strain. And so much of that strength comes from how roses are in relationship to one another and in community. A whole rose is better equipped to withstand rain than a single petal is. That teaches us a lot about interdependence—as solidarity, as a practice in power with.

Amirio: One of your interests is tracking how capitalism has co-opted the incredible, profound magic that roses offer us in service of beauty culture. Can you say more about how rose medicine has been weaponized to feed into devastating beauty constructs and ideals?

Kate: When I use the term beauty culture, I am not thinking about how we might draw from our own ancestral lineages, for example, to cultivate practices that make us feel beautiful in our bodies. That’s different. I'm talking about a culture that's rooted in consumerism, colonialism, commodification, and resource extraction. I'm thinking of beauty standards that come from a corporation—not from a community—that aims to sell shit and sow supremacist ideologies in consumers. The journalist Jessica DeFino has written a lot about this topic, and I value her take.

Beauty culture shows up in this idea that being “beautiful”—as in, complying with corporate-created norms—is a moral imperative. To have blemish-free skin or a certain type of hair texture are indicators of beauty culture at work. It’s a system of supremacy that seeks to make some bodies—e.g., white, thin, able-bodied bodies—more valuable than others. That's what I mean when I talk about beauty culture.

I love roses and rose medicine, and what they can do to strengthen our skin and heal inflammation. But I'm increasingly troubled by how often I see rose medicine invoked as a remedy for mature skin and aging. Mature skin and aging aren’t actual problems! We must divest from beauty culture the same way we must divest from fossil fuel companies. We need a mass, collective effort to challenge the norms that keep us compliant, self-centered, and sick. Because spending so much of our time—and money—fearing life (and its passage, and impact) is a rejection of the gift of the rose. To me, so much of the beauty of rose and rose hip is in how the flower and fruit relate to one another! So I would love for our connection with rose medicine to be more about how part of what makes something, or someone, beautiful is how it exists in dynamic, vibrant relationship with other beings. Mostly, I want to move away from the idea that beauty, morality, and youth are one and the same. Really listening to roses over the years has shown me that’s definitely not true.

Amirio: I’m obsessed with this idea that we have to divest from fossil fuels while also divesting from beauty culture. Can you talk about the threat that beauty culture poses to planetary health? Why is beauty culture bad for us and our plant kin, animal kin, and the planet?

Kate: The beauty industry is one of the most fossil fuel-consuming industries on the planet. And because it represents something we consider superficial, it doesn’t receive the ire it should. There's very little regulation in the beauty industry, especially in the U.S., so you can put almost anything in products—even those that are “natural.” You can add preservatives that are petroleum-based, or use packaging that's petroleum-based.

When it comes to roses, I've noticed there's a desire for rose essential oil rather than rose hydrosols. Real rose essential oil is massively expensive because a ton of roses are needed to extract a small ounce. Producing it requires a massively wasteful process. Meanwhile, with rose hydrosols—sort of the steam of a rose—you're gathering a rose’s essence in a different way, and there’s much less waste.

Within beauty culture, there’s this eagerness to participate in the “shelfie” trend (the fact that even exists causes me massive pain). The beauty industry is a massively consuming one that does a huge disservice to women, femmes, and gender non-conforming people. And it’s an industry that seeks to advance a limited and ecologically unsound vision of beauty.

Amirio: In all, how can roses help reorient us, given where we are as a species? What are those core things that roses can teach us? What are the main lessons you hear when you listen intently to roses?

Kate: Roses remind us about the necessity of caring for one another. I know I mentioned this earlier, but I love the chapter in Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask where Mary talks about roses as a conduit for community care—for recognizing that no one's well until we're all well. Roses are instructive in ensuring that everyone in our community is healthy; they help us understand that we belong to one another. That's a major gift.

Also, roses can help us set boundaries. I haven't talked much about thorns in this conversation, but there's so much about thorns that is significant, including their ecological role and symbolic meaning. A rose’s thorns remind us about the necessity of setting healthy boundaries: we get to be discerning about who we open up to and why.

And roses remind us that beauty is a true animating life force—and isn’t optional. Beauty is foundational to living a good life and must be part of our dreaming processes. Beauty needs to be part of how we envision liberation and foundational to how we create spaces for one another to bloom.

Kate’s Recommended Resources

Orwell’s Roses, Rebecca Solnit

Parwana: Recipes and Stories from an Afghan Kitchen, Durkhanai Ayubi

The Land In Our Bones, Layla K. Feghali

Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask, Mary Siisip Geniusz

Seed Medicine, Keitha Thuy Young

Living Library, Herban Cura

Learn More About Kate’s Work

James Bridle, Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence, p. 64

James Bridle, Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence, p. 122

James Bridle, Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence, p. 74

Taschen, The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images, p. 162

Kate: Check out Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit for an in-depth look into the journey that many roses take from farm to grocery store.

🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹