The history of the human world is one of citation. Take music: its evolution is grounded in observation, mimicry, remix, borrowing, worship, theft, and obsession—Little Richard materializing from Mahalia Jackson’s God-loving thunder, The Beatles emerging from the Big Bang of Little Richard. Or look at our literary canons: some of my favorite writers are meticulous, generous geographers who chart maps to the origins of their words in the form of bibliographies, footnotes, and acknowledgments, all foregrounding that writing is a relational endeavor. The whole of our reality—our inherited and created cosmologies and cultures, rituals and customs, politics and economics, moral codes and norms—is evidentiary of humanity being “embodied indebtedness.”1 What we do today is always already in conversation with past events, bodies, and ideas, for better or worse. Even the planet itself is a propagation of an ever-unfolding Great Emergence we still have yet to fully comprehend.

Cultural theorist Astrida Neimanis writes that “no one ever thinks alone.”2 I’ll expand that to say that no one ever does anything alone—especially become. Yes, I mean that in a sort of lyrical, existential sense: to be human is to be a remnant of a remnant of a remnant cohering into a self—a group of stacked-up hauntings enclosed in a trench coat cosplaying as an individual. I also mean that literally, in a material sense.

Again, Astrida: “[T]he human is always also more-than-human.”3 We’re all holobionts—multi-entity soups—with our guts full of microorganisms, our bodies fecund with water, and our ancestry shared with the entire expanse of life on Earth—including plants. I’m moved by the idea of our lives being weaved together by the living and by the dead: by phyto-phantoms (in the textiles we wear, in the fossil fuels we extract), geo-ghosts (in the pacemakers we install, in the drones we deploy), and myco-haints (in the food we bake, in the buildings we dwell in).

Especially amid the continuing devastation of climate chaos, perhaps one of the most urgent objectives of our lives is to deconstruct the trompe l’oeil of personhood, that consequence and engine of these justice-starved times, by remembering our citational selves.

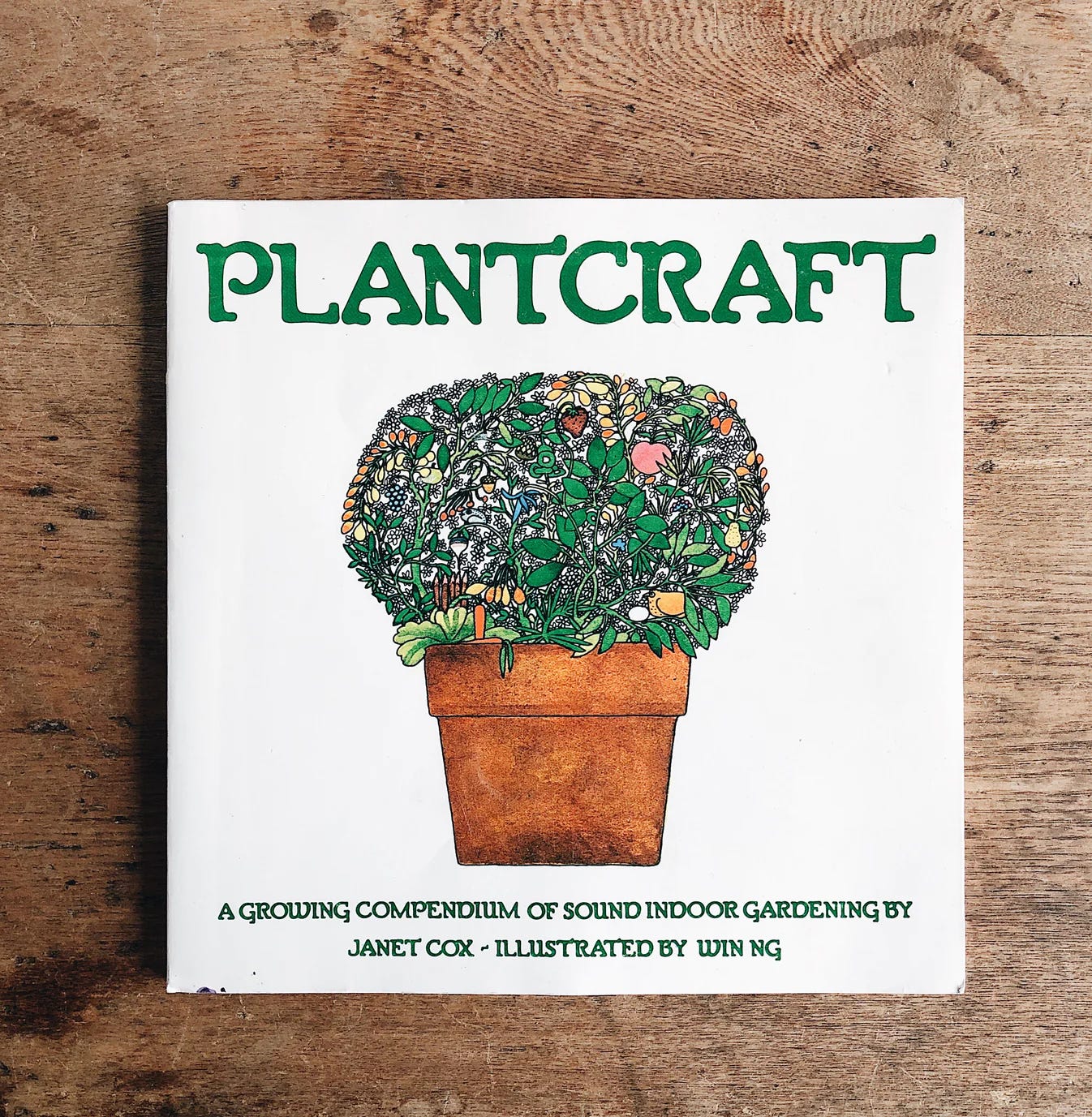

“Ain’t nobody come from nothing”—including this newsletter. An incomplete archive of the whos and whats that have been critical to midwifing PLANTCRAFT: the writing of Jamaica Kincaid, especially A Small Place and My Garden (Book):; the art of Win Ng, including that featured in this newsletter’s titular inspiration, Plantcraft: A Growing Compendium of Sound Indoor Gardening; the evergreen wisdom of Alexis Pauline Gumbs and Zora Neale Hurston; the plant disciples who left behind botanical monographs, herbals, and other crucial records; my Granddady William, who modeled a love and reverence for plant life; my Uncle Doc, who encouraged my queer younger self’s romance with floral beauty.

This is my windy and long-winded way of saying that I’m deeply grateful to YOU and all the wellsprings of inspiration that have made PLANTCRAFT possible. Truly. Now: onto this month’s Broadcast dedicated to the world of fictional plants! (And, as always: 🇵🇸🇵🇸🇵🇸)

There’s Audrey II, the blood-hungry, Earth-colonizing plant at the center of Little Shop of Horrors. You may also be familiar with folkloric mandrakes, those human-plant hybrids that were a mainstay in medieval bestiaries, or Ents, the ambulatory tree-like figures that inhabit the Lord of the Rings universe. Within the narrative arteries of our lives is a constant flow of fictional, speculative, hypothetical, and dreamed-up vegetal forces that run the gamut in terms of how they imprint upon human life.

Some are tools for coercing specific arrangements of human thought and behavior (see: the Garden of Eden). Others are interfaces for processing our anxieties regarding the unknowability of plants and other Others—an opacity that may obscure a “wicked” hidden agenda, like a scheme to reverse roles and dominate the dominating (see: Audrey II, again). For me, the most generative capability of imaginary vegetation is offering us an opportunity to hold our current human-plant reality in our hands—to turn it over, inspect it from all angles, confront it, break it open—and “[unlock] new ethical and political opportunities” in our human-plant intimacies (e.g., should plants be able to vote in our democracies?). For this month’s Broadcast, I’m crawling into the possibility-rich tear in the fabric of our world left by fictional plants with guest Oscar Salguero.

Oscar is an archivist, book curator, and independent researcher based in Brooklyn, NY. In 2021, Salguero curated Interspecies Futures [IF] at the Center for Book Arts. The show marked the first public survey of bookworks by emerging artists working at the intersection of speculative fiction and interspecies possibilities. Salguero founded the Interspecies Library in 2019.

Over Zoom, Oscar and I discussed the potency of books, how the history of fictional plants reveals our fear of vegetal monstrosity (and maybe of our inner human monstrosity), whale songs and plant music, and speculative plants we wish were real. This is a juicy one. As always, like, comment, and share! (This conversation took place in February 2024 and has been edited for clarity.)

Amirio: I first stumbled across your work when I was on the Internet doing some rabbit-holing, and I came across the Interspecies Library and was like, Holy shit, this is amazing and so cool. Can you talk briefly about the Interspecies Library and how it came to be?

Oscar: It started because I never saw an Interspecies Library. I never found one. It’s one of those things that you wish existed. If something doesn’t exist, you give it a shot.

The origins of the Library is an interesting subject for me because I’ve loved books since I was a kid. I remember going to Grandma’s house and reading old encyclopedias. I didn’t understand what they were talking about because I couldn’t read, but books became these magical portals into new ideas and worlds.

I grew up in Peru. I didn’t grow up with pets. I didn’t even grow up with many plants around me. But that craving for other kinds of presence in my space came back to me later. I came to the United States as a teenager, studied industrial design, became a designer, practiced as a designer, started living with roommates in New York, and then, five years ago, I got married. My wife grew up with plants and pets and encouraged us to do that—and I welcomed it. I was hesitant at first because I didn’t have that experience, but I enjoyed it a lot when it happened. We now have a cat and a lot of plants. I started to see this connection between my passion for books, this transformative experience I was going through of living with other beings around me, and this feeling that around the world, many artists were awakening to a consciousness of the damage we’re causing to ecosystems and the Earth.

We’ve been so selfish since the dawn of our species, and we are seeing the results of that selfishness faster than any other generation and in real time. Many designers and artists my age and younger are looking at and producing books on climate crisis, species extinction, and more. They are making books that don’t make it to bookstores, or they’re not making books to necessarily put on people’s shelves because they have no means of producing large quantities. They don’t get contracts to produce thousands of copies. Nonetheless, they feel the need to produce these books as a manifestation of their research. So I started contacting them one by one—young artists, designers, and researchers making interesting books about our relationship with other species, from insects to animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, and beyond. And little by little, I started building the concept of an Interspecies Library. I thought, Maybe this is a new type of library. That is the beginning of the idea. It’s a library of interspecies awareness; it’s an independent archive. I open my space to whoever contacts me or finds out about the project. The Library is a bunch of shelves in my living room space in my one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn. My wife is very gracious. She is happy to let our private space be a welcoming space for people interested in the subject.

Amirio: I love that the Library is in your home but is still a communal, public setting. It blurs lines and feels like such a loving act of “public domesticity.”4 And for this conversation, I love that we’re thinking about books in relationship to plants because vegetal life is essential to storytelling, primarily in a material way. We’ve always relied on plant materials to create books and establish language. Even thinking about our reliance on breath to foster oral storytelling traditions, plants help make that possible. When considering the content of books, plants show up in many different ways: as metaphors, moral guides, and central characters.5 I’m excited to dive into those ideas more, but I first want to learn more about your philosophy regarding books. Why are they so potent and powerful for you? You called them “portals.” Why books and not other mediums of expression?

Oscar: I’ve always had this intuition that the book is perhaps the most interesting artifact we have created in terms of sharing information from humans to other humans. That’s because, in part, they’re so low-tech: all you need is a surface that you can imprint something on with any method you have. I was a part of a talk a couple of weeks ago with Aidan Koch, an artist who draws environmental comics, and we were talking about the idea of “publications.” You can argue that the early drawings inside caves, like of hands or animals, by early humans are a mode of publication. From the beginning, there has been a human need to manifest or express ideas that we have in a format that other people can see and even touch. So, the book has become this low-tech medium that has been with us for thousands of years across different cultures.

Something we intuitively like about books is that they’re like us. They have an expiration date; they can deteriorate. They’re physical; they have materiality. They have a smell, they have a tactility, a weight. They engage all of our senses. Another thing that I really enjoy about them is that they’re a slow medium. You can engage with them at any speed you want and jump around at any pace you want from any point you want. They’re intimate and powerful that way.

Amirio: I’m excited to think more about books with you, especially through the lens of books that feature or focus on speculative, fictional plants. While doing some research, I thought about how every “real” plant we engage with is speculative in some sense. After all, can we truly know plants around us through our limited human sensoria? For instance, when we’re thinking about a rose or a daffodil, we can only know them through our limited faculties. From that perspective, plants are only partially legible. They have an opacity that has inspired an entire literary canon of plants that don’t exist (at least to our knowledge!).

I want to touch on you growing up in Lima, Peru, as a young reader. What were the first fictional plants you encountered in books or other mediums? Were there fictional plants in your life through the folklore, mythology, music, or art around you? What were those first encounters like, and what did those encounters invoke in you? Was it awe? Was it fear? Was it curiosity? Something else?

Oscar: I can think of a couple of examples. In terms of mythology or folklore, we have a seed in the mountains of Peru called huayruro (Ormosia coccinea). It’s a beautiful seed that mostly grows in this part of the world and that is half red—an intense red—and half black. It’s very unusual and beautiful. Giving this seed to others is common for warding off bad spirits, protecting you, or giving you good luck. The seed was a nice introduction to a world of connectivity with plants that escapes rationality or dimensions we can understand. I recently went to Virginia for Christmas to see my family, and my mom gave me a glass container of huayruro seeds she got from her recent trip to Peru. That connectivity is still going on.

Another weird and interesting example is also connected to Peru. When I was growing up, for some reason Peru’s national TV station broadcast a number of fascinating Japanese shows dubbed in Spanish (this is in the 90s). They were not cheesy. They were quite sophisticated puppet shows. They were like The Muppets but focused on reenacting folk tales from ancient Japan. And I remember very specifically that one of the episodes was about a peach. This old couple found a peach by the water, and it was gigantic. It was fat and big, and they thought it was lovely. They took it home, and then a little boy came out of it. This is the tale of Momotarō, or Peach Boy. It was so funky—to see a kid coming from a peach. And the idea is that the old couple always wanted to have a kid and then they found one inside a peach. A human coming from a fruit is science fiction, in a way. These old folk tales use fantasy and fabulation to offer moral stories or present beliefs in a memorable format. I appreciate that, and I will never forget the two examples I’m sharing with you because they introduced the idea that when we use fabulation as a method, we can attune ourselves to different ways of being that are not normal to us—and different worlds that we cannot explain within our human terms. That sense of mystery and magic is something I always gravitated towards because it humbles us. We don’t know everything. There’s so much we don’t know. And that’s nice—to accept that we don’t know everything and that we can play with our boundaries.

Amirio: Thinking about your library, are there additions that focus on or feature speculative plants? If so, are there any examples that you’re excited about and that stand out to you?

Oscar: My library has been growing organically, which is a nice word to describe it. People contact me at this point with projects to add, or I find them. The library doesn’t lean into specific directions in terms of species. I mean, last week, I got something on bacteria. I’m expecting a book about radioactive fungi from Slovenia this week. But in terms of plants, I pulled a couple of things. (pulls out book selections)

This is a book I got in 2021 from University of the Arts Bern students in Germany. It’s called Botanical Fictions: The Herbarium of the Future. It’s a really nice book because it came out of a workshop with students. The prompt created by Offshore Studio (Isabel Seiffert and Christoph Miller) for the students was to dream up future and imaginative plants that may exist in speculative “what if” scenarios. And everyone developed these wonderful drawings or 3D models and sketches in response. The class is part of a visual communication design program that essentially challenges them to think about plants in a scientific and fictional way. I have a lot of interest in the way students think about speculative interspecies relationships.

Another book that I’m actually reading right now is Radical Botany: Plants and Speculative Fiction. It’s a fantastic book. I work at the Grolier Club, a museum and private bibliophile club that has a wonderful space for book-related exhibitions. It’s a really unique space in Manhattan. One of my colleagues reads voraciously, and she reads fast, which makes me very self-conscious about my reading (laughs). I read very slowly! I’ve been reading this book for a few months and am only halfway through. I take so many notes, and I stop at every word. On every page, I’m like, Wow, this is fantastic. I highly recommend it. It is an innovative look at the West’s relationship with vegetable imagination through literature. It starts in medieval times, goes through all eras until modernity. I like the constant references to obscure books. For example, it introduced me to Niels Klim’s Underground Travels (1741), a book by Norwegian-Danish author Ludvig Holberg. In it, the main character, Klim, goes on this weird trip that leads him to an underground entrance through which he can access a parallel world, another reality. At one point, Klim ends up in a kingdom dominated by sentient trees who have achieved a beautiful society that doesn’t require any rulers because everyone is constantly participating in the benefit of the community. At first, Klim is weirded out by this, but then he realizes how fair the trees’ world is compared to his. He thinks, Wow, their society is more humane than mine.

I find these stories interesting, these allegories. Back in 1741, someone was already thinking about the perspective of another species and how they operate. In Niels Klim’s Underground Travels, the trees cannot move; they live through communal growth. Their existence isn’t an individual thing. At some point, Klim starts thinking that having legs and moving around is a detriment because his freedom depends on him moving around and constantly thinking about his own survival. The trees, by contrast, operate at a different speed and by a different sense of time.

There’s also the book Evil Roots: Killer Tales of the Botanical Gothic, which I also highly recommend. There was an explosion of stories in the Gothic genre wherein plants take over humans, a fear that seems to be justified by how little we know about them. They’re almost like monsters, and they’re sentient. As a species, we go through these stages: first, we don’t understand something, so we fear it. Then we start to open our minds to it, so we explore. Evil Roots: Killer Tales of the Botanical Gothic encapsulates a whole era when Western thinking was prejudiced against the world of plants—and when botanical beings were seen as mysterious, and overpowering.

Amirio: Thank you for that deep dive! I’m so excited to purchase some of those books for my collection here at home.

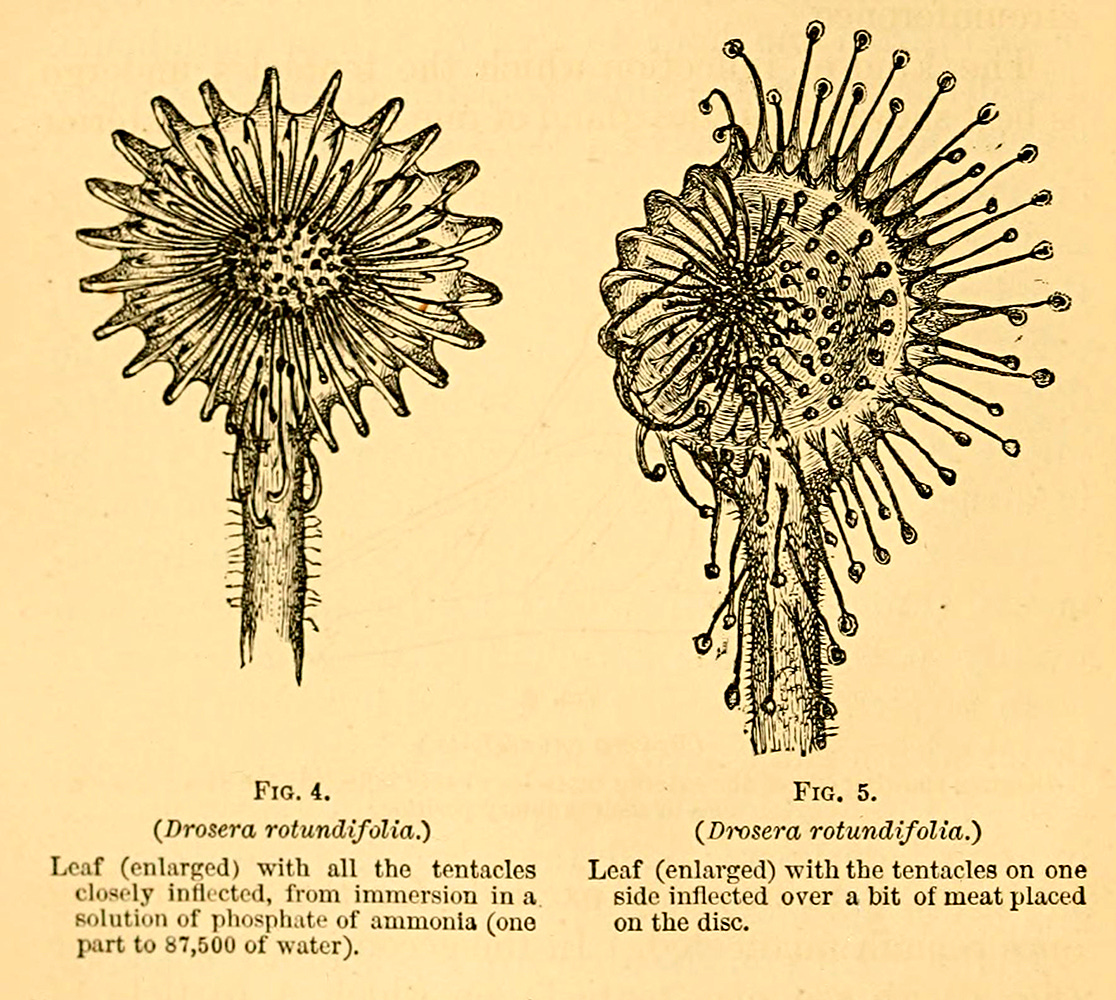

I want to spend some time on the interaction between the speculative and the empirical. Among the books you referenced, you mentioned one featuring a character who travels to this other bizarre world. That’s a fascinating setup because we don’t have to travel to new worlds to experience the peculiar. The world of botany, for example, is weird as fuck. There’s so much to learn about our present botanical reality. I’m also thinking about Darwin, who grounded the fantastical in the scientific. So much of his work is speculative, speaking to the fact that our reality is deeply strange, and we’re constantly trying to figure it out. Maybe we’ll get to a place where we feel, Well, perhaps we’ll never fully comprehend what’s around us. There’s a beauty and magic to that.

I was reading recently and came across this line: “You can be honest with fantasy.”6 I love the idea that the space of the hypothetical can be a place for working out ideas and getting to certain truths. Where do you see examples of the interplay between speculative and actual botany, especially in literature? I wonder if you’ve seen moments where those two things are in dialogue—imprinting upon each other, becoming reliant on one another.

Oscar: I was reading this book about plants growing in places that have been affected by nuclear spills, like Chernobyl. And the idea of mutations comes up…an interesting subject. Have you ever watched the movie Annihilation?

Amirio: No, I’ve never heard of that movie. What’s it about?

Oscar: It’s a science fiction film from 2018 with Natalie Portman based on a book of the same name by Jeff VanderMeer, an author of a genre known as The New Weird. It’s a strange story about this place known as Area X, a location surrounded by a gleaming wall known as “The Shimmer,” which the military is monitoring. They’re trying to figure out why it popped up and why it continues to expand. They go into Area X, and they see plants and animals mutating in anomalous, very unpredictable ways. And it’s driving people crazy. It’s a very odd story, and the film is underrated, but it’s really fantastical. I talk about it because of its place in speculative and imaginative thinking.

Stepping back, there’s this book from 2016 called The Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness by Michael Marder and Anaïs Tondeur. They’re looking at plants and how they access their environment after nuclear spills. People think plants are docile organisms, but in reality they’re always working. They’re communicating via their roots, their mycelial networks. They’re communicating about changes in their environment. They’re adapting. They’re changing all the time. We just don’t see it, we don’t perceive it. The Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness brings all that to light. Here’s a quote from it:

For the plant, the ongoing monitoring of environmental conditions in the place of its growth is a run-of-the-mill operation; for us, who are accustomed to thinking of plants as passive beings devoid of consciousness or as persisting in a state of torpor at best, it is extraordinary.

So, in real life, like you’re saying, plants are already extraordinary organisms. We just don’t see them. They don’t have that kind of sexy effect like a science fiction film might have.

Plants are very complex. They’ve been here millions of years before us, and they’ll probably be here after us. We must alter our imagination and start to consider them as higher—I don’t know—“higher organisms.” I don’t know how to adequately express how I’m thinking about them because our language is limited. That needed shift can happen when a lot of people bring up this thinking across the board—and that’s one of my motivations for documenting and archiving the books in the Interspecies Library. They’re manifestations of this evolution in our thinking. Nowadays, we don’t have a Charles Darwin or other outsider genius personalities. Rather, we have the work of thousands of people scattered all over the world producing insights and moments of lucidity and observation that, as an aggregate, can generate a change. So, on the one hand, science fiction, like Annihilation, makes possible worlds more visible and visceral. Nonfiction, like The Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness, reveals the real in the speculative and the real effects of plants’ intelligence and way of being in the world.

Amirio: As someone who’s archiving this turn in thought and seeing how these different streams of work regarding our relationship with plants and other organisms has become more diverse, decentralized, and evolved over time, how have you been transformed by engaging with all of these schools of thought produced by thinkers, artists, and more worldwide? And where do you see us going in our human-plant relationships?

Oscar: The shift is slow, but it’s happening, especially with the spread of other technologies or the use of different mediums, like this kind of newsletter. I see there are YouTube channels that are dedicated to plant care—something that’s growing and connecting us across languages. It’s such a beautiful subject. In my personal experience, I, like I said, didn’t grow up with many plants. Now, I don’t see myself without them. You also have these “getaway” hospitality businesses that are trying to get you to leave and spend a weekend in nature. They’re pushing for us to basically be surrounded by plants and vegetation—beings that have always been there. I also see a lot of artists trying to figure out ways to elevate or understand the communication of plants. That’s an area that I’m really excited about at the moment. A lot of that interest is driven by the fiction side of things with writers like Ursula K. Le Guin, a fantastic author, writer, philosopher. She left many incredible short stories, and in one of my favorites, The Author of the Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics, she introduces the concept of therolinguistics, or the study of the language of other organisms.

In this short story, which she wrote in 1974, she imagines a field of research that doesn’t exist, however, in her alternative reality, there are already humans trying to understand the language of ants and sloths and penguins. What are they really trying to say on their terms, not in our languages? She suggested that plant communication would be the most difficult to decipher after animal communication. How do we understand what plants are trying to say to each other? She called this field phytolinguistics. That has really captivated me because I am closely following the area of interspecies communication, which is a developing field right now. Because of AI, we’re now able to capture, gather, and process data that we were never able to see or perceive in the area before, as in the case of whale communication, for example. Now we’re recording whale songs and trying to see if there are any patterns, semantics, or changes in their communication across time.

There’s a research initiative called Project CETI—Cetacean Translation Initiative. The researchers for that effort are trying to first understand whales’ messages and then, potentially, predict their next response or even say something back. It sounds crazy, and it’s never really happened with other species at that scale. We enjoy a certain level of communication with animals. With pets, communication happens at an emotional or maybe gestural level, but we’ve never had this sort of two-way transmission that’s more sophisticated. So, I am following what’s going on in the world of linguistics, AI, and communication with animals at the scientific and academic levels and also at the artistic level. I’m looking at how artists are interpreting the language of beetles, the language of beavers, of fly larvae, of bacteria, from a poetic perspective. The area of plant communication is one where I’m seeing some development, too. This is an example of something that is still so mysterious to us and that neither the scientific nor artistic worlds have many answers for.

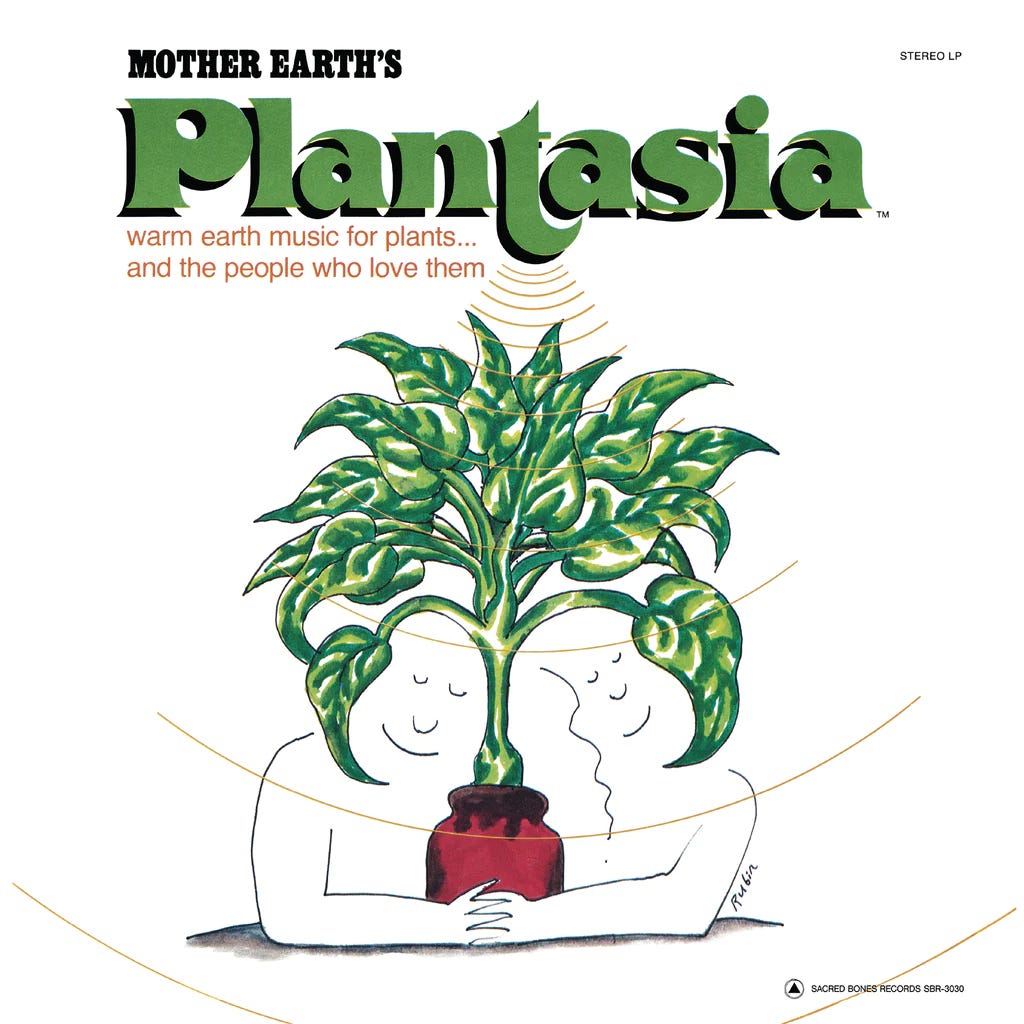

So back to your original question of how I see the future of our relationship with plants, I think there is a lot of promise in the sense that I see both the rational aspects of science and the artistic side of things trying to get to that next level of understanding. Communication might not necessarily be the goal, but rather some sort of comprehension. This is an area that has evolved a lot in the last few years. As far as the next five to ten years—I don’t even know how to speculate on that. There have been some weird projects in the past. For example, do you know the album Plantasia?

Amirio: Yes! The seventies were such an interesting time when plant fascination became mainstream. In the same canon of Plantasia, you also have Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants.

Oscar: Yeah, exactly! Things like that are coming back. So, Plantasia came out in 1976. In 2019, the original album was reissued. Through the album re-release, we see that people were not only trying to find new ways to connect with plants but also looking at past attempts—which are resurfacing now because they got somehow lost in the streams of content. Those past attempts were funky experiments that happened and were forgotten, but now we’re looking at them with different eyes. We’re looking at them saying, There might be something there. It may be a little jokey to make up an album for plants, but what if there’s something there? What if there is an attempt here at kinship that is really endearing? I’m monitoring this renewed curiosity from my perspective as a book person and someone who’s looking at artists exploring our relationship with other organisms.

Amirio: Returning to one of my earlier questions, how are you being transformed by all this? You mentioned feeling humbled earlier. Is humility the place where you still land?

Oscar: I feel a lot of humility. As a designer trained in human-centered design, everything I’ve been taught no longer feels right. I cannot imagine my reality moving forward without considering other organisms. I used to kill cockroaches, and now I don’t even consider that as an option. I just put them in a plastic bag and leave them outside. Even with spiders, I don’t kill them anymore. When you’re a kid, you perceive them as scary, and so you kill them. But now, I believe all organisms deserve to live. They each have a role and are doing something—even if we don’t appreciate (or understand) what that is. My perspective is completely different now. I see a lot of people my age and younger becoming more sensitive about how we treat other species, and that gives me optimism. That gives me hope.

Amirio: You mentioned the 2019 re-release of Plantasia, and now I’m thinking about the pandemic. During the height of COVID, folks started to seriously consider how something thought of as “lowly,” this viral presence, is completely capable of toppling our world. Our hierarchies were flipped, and there was something so humbling about that. From COVID, I’m optimistic about us reawakening to not just animals and plants, but water, minerals, and more.

Oscar: Yeah, I agree with you. I’ve started to think of other organisms in a completely different way. I remember an anecdote from a couple of years ago: I had a really strange episode of acid reflux.

Amirio: (laughs) This sounds terrifying!

Oscar: It was terrifying! I felt like I couldn’t swallow my saliva without feeling pain. I told that to an artist who’s been investigating bacteria and microbiomes, and he told me, Maybe your microbiome is telling you that you need to change your diet. And so I changed my diet completely. I don’t eat meat anymore; I eat more vegetables than I’ve ever eaten. And I feel much better. I don’t have those episodes anymore. So even these trillions of organisms inside my gut told me, You are not in control. Maybe we want something else now. Your diet is not healthy. That story reminds me that none of us are individuals. What is that quote? “I contain multitudes.” Moments like that have really shifted my perspective regarding the idea that humans are the “supreme species.” That’s not the case. And I thank these artists for opening up my eyes and imagination to perceive the world differently. If it wasn’t for the Interspecies Library, I don’t know if I could have achieved this level of awareness.

Amirio: I was reading up on the work of artist Aaron McIntosh, and I came across their Exuberant Botanica project. The project is an act of speculating “on the kind of herbs [LGBTQIA2S+ folks] might wish were readily at hand to combat xenophobia and queer violence.” The idea of crafting a hypothetical queer herbal resonated with me and inspired my final question: Is there a speculative plant that you wish existed in this world?

Oscar: That’s an awesome question. There is this book from 1976 called Parallel Botany by Leo Lionni. I haven’t read the entire book. In fact, I don’t own it yet. I’m trying to find a copy. But I’ve seen online scans of the pages. The book features all these wonderful imaginative plants. One of them is kind of invisible. There’s another that disintegrates when you try to engage with it, and that’s the one I want to exist. You know how we like tulips and remove them from their place? It would be so amazing if there were a plant so beautiful that as soon as you want to touch it, it just disintegrates.

Oscar’s Recommended Resources

Covert Plants: Vegetal Consciousness and Agency in an Anthropocentric World (2018), edited by Prudence Gibson and Baylee Brits

Plants in Science Fiction: Speculative Vegetation (2020), edited by Katherine E. Bishop, David Higgins, and Jerry Määttä

Death by Landscape (2022), by Elvia Wilk

Beyond Plant Blindness: Seeing the Importance of Plants for a Sustainable World (2020), by Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir andMark Wilson

Learn More About Oscar’s Work

Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, p. 4

Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, p. 9

Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, p. 2

Amirio: I’m borrowing this phrase from maura chen’s fantastic inaugural drafting curbside newsletter missive.

Amirio: For more on plants’ role in nurturing humans’ narrative traditions and technologies, read the journal article “The Stories Plants Tell: An Introduction to Vegetal Narrative Cultures” by Frederike Middelhoff and Arnika Peselmann.

Amirio: This quote is pulled from the “Radical Fantasy” interview featured in the Autumn 2023 issue of BUTT Magazine.

This is such a fascinating conversation—especially the way you’re bridging the gap between fiction, science and art to explore our relationship with plants. 🌱👏