PLANTCRAFT: Jayson Maurice Porter and Mrs. Delores Scott Recover Black Botanical Histories

Broadcast 007

In archaeological terms, “midden” refers to domestic garbage left behind by ancient cultures. Sifting through layers of refuse can help us understand the day-to-day lives of past civilizations. We get valuable insights into how they lived by looking at what they threw away. In practical terms, we learn more about ancient peoples from their refuse than we do from the monuments they leave behind.1

On what we leave behind:

i.

Once again, in the United States, we’ve handed ourselves over to a carnival of coarseness.

Of all the callousness innovated and unleashed by the latest ruling regime, I’m most hollowed out by our nation’s little acts of acquiescence, by our preemptive obedience,2 by our capacity to yoke our collective fate to the poisoners of our food, the murderers of our neighbors, the deniers of our disasters. More than this first-wave sludge of executive orders congesting our screens and senses. More than the exile of science. More than the governing troupe of clowns who declare eugenics as destiny, profit as god, losing as rationale enough for disposability, and winning as the basis for personhood. Instead, I’m most gutted by the unceasing flow of our work emails and office huddles—evidence of a self-inflicted glamour to believe that nothing else could be more critical, that turning our heads away will keep the hounds at bay. I’m most gutted by the self-censoring of our interpersonal actions and words in service of uniting and coming together, of valuing all viewpoints and opinions. Even the smallest concessions fuel the coronation of one evil after another.

If we continue to remake ourselves, bit by bit, to be amenable, dedicated, perfect citizens of this ruin-as-nation, I fear what we’ll find among the remains, in the psychic and physical midden, of this era of American life: all the care we could have dispersed, all the beauty we could have asserted, all the bones we can’t reanimate.

ii.

A few weeks ago, I read my work in public for the first time at a cozy gallery tucked away in West Philly. By invitation from Thick Press, a publisher of texts related to “working and living in the thick of human experience,” I, alongside a semi-circle of fellow readers, presented an excerpt from my contribution to Thick Press’ An Encyclopedia of Radical Helping for an intimate audience. I offered a few lines from my entry on food sovereignty, which doubles as an ode to June Jordan; Melanie shared a vision of an anti-racism court system; Allan dove into a history of clouds as metaphor and foregrounded the usefulness of fragments as a framework; Erin uplifted the criticality of public benefits and ongoingness; Denise celebrated radical papermaking; and Lindsay ignited the room with their words on revolutionary mothering.

Somewhere between the readings, the audience Q&A, and exchange of ideas and insights between all who were present, it became clear just how much our communities can do to actively confront, disrupt, and end the carnival of coarseness—further accentuating how timely and crucial efforts like An Encyclopedia are. A “collection of interconnected entries on helping and healing by over 200 contributors from the worlds of social work and family therapy; art and design; body work; organizing; and more,” An Encyclopedia forms a spiral of strategies—versus a spiral of foreboding—the provides some solid ground while adrift in an unsteady landscape.

I envision that the encyclopedia, in addition to many of the cultural and creative artifacts that have and will come from this moment, will be helpful for the present and the future—tattered, well-loved, and inherited by someone far-flung in a far-off time, in search of an instructive archive, in search of a compass, in search of a warning. How can we ensure our refusal doesn’t become refuse now or later?

We are a people. A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children, and, if necessary, bone by bone.3

The story of PLANTCRAFT truly begins with the wisdom of my maternal grandfather, Granddaddy William.

As I’ve recounted many times before, my grandfather’s tender land stewardship has not only provided material sustenance for my family in and beyond South Carolina but has also been a steady source of inspiration for my writing, my values, and my day-to-day work. In more ways than one, I would not be here without him and his deep, deep intimacy with one of our oldest elders. My grandfather’s genius lives in me, connecting me to a vast lineage of earth whisperers who kept passing down all they knew.

At this hour on the world’s clock, to borrow language from activist Grace Lee Boggs, it’s increasingly evident that it’s time to reconsider how we gather and safeguard whatever we can—the knowledge, the skills, the stories, the genius of our forebears—to support the wayfinders of today and those who will pick up where they leave off tomorrow. As our digital archives become increasingly endangered by tech elites, as our physical archives become increasingly threatened by a planet heated into malfunction, rigorously documenting and preserving all that we need to survive is one of the core imperatives of our time. In this month’s missive, I dig into some of the Black botanical histories that must be a part of our renewed schemes for documentation and preservation with Dr. Jayson Maurice Porter and his grandmother, Mrs. Delores Scott.

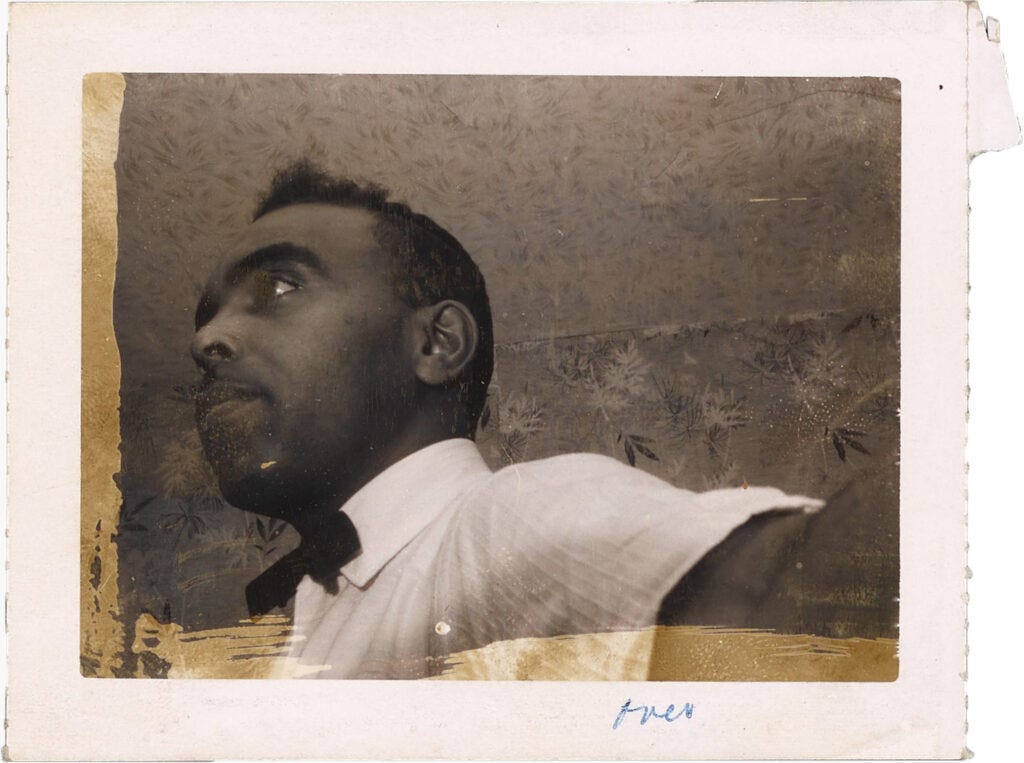

Jayson is an environmental writer and historian, and a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of History at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is also an inaugural Black and Indigenous Climate Futures Faculty Fellow at the Harriet Tubman Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. Jayson is from Philadelphia and was raised between Arizona and Mississippi, but he was born in Maryland like his great-grandmother Winona Spencer Lee (1909-2012), who, until the early 2000s, worked on family farm land near where their ancestors were enslaved on the state’s Eastern Shore. Inspired by his family histories in Maryland and his time in Arizona and Mississippi, Jayson’s research specializes in the environmental histories of agrarian revolution and land reform, agrochemicals and agribusiness, food systems and foodways, and Black and Indigenous ecologies in Mexico and the Americas. He is an editorial board member of the North American Congress for Latin America (NACLA) and Plant Perspectives: An Interdisciplinary Journal.

I’ve long admired Jayson’s work, particularly his research that sits lovingly and critically with personal and national records, and I was delighted when he agreed to an in-person interview with his grandmother at my home in Philadelphia. In PLANTCRAFT’s first-ever three-person conversation, Jayson, Mrs. Scott, and I dive into personal land narratives, Crisco’s connection to the afterlife of slavery, guidance for collecting familial histories, and sesame’s forgotten centrality across the African diaspora. May the following words reach you and live in you long enough to reach whoever is beyond our time. (This conversation took place in November 2024 and has been edited for length and clarity.)

AMIRIO: I always love to start with origins. I grew up in the Tidewater region in Virginia, so when I talk about myself and my origins, who I am, that cannot be divorced from where I grew up. So, I always talk about the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

When thinking about origins for you, Jayson, I’m thinking about how you’ve discussed growing up in so many diverse places, from Tucson, Arizona, to Jackson, Mississippi, and I wonder if you could talk about how growing up in such diverse terrains has impacted and shaped who you are.

And then for you, Mrs. Scott, I want to know more about the places that raised you. Where did you grow up? What landscapes do you claim as home? And what were the sights and the smells and the tastes of those places?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I was born and raised in Philadelphia. During the summer, I spent time in Snow Hill, Maryland. If school closed on Saturday, I was on a bus or in a car going to Snow Hill, Maryland, on Sunday. My mother didn’t spend any time getting us ready for outside. We would always say, Ooh, we have to spend so much time outside, when we went to Maryland. One reason why she did that was because my grandmother, her mother, had a farm—a 300-and-some-acre farm—and my mother felt obligated to help her how she could, both financially and by sending us to our grandmother, which meant less work for her. We helped with whatever—not that we wanted to. That was hard work.

JAYSON: Do you remember some sounds or any particular animals from Snow Hill?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: We were so far from the city. There was not that many sounds, I would say, other than the animals. First thing in the morning, you would hear the rooster, the male chicken. (mimics sound) So then you knew that, Oh, it’s time to get up and have breakfast and prepare to go out in the field. Of course, the animals had to eat. You maybe didn’t have to worry about going to the field, but you had to get up and help with the animals.

Even the food was different. I never said that before. They really made breakfast on Sundays—and don’t let somebody be coming. And don’t let it be the minister! Do you know what a parlor is?

AMIRIO: I don’t.

JAYSON: Like a bar?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: No, sir. The parlor was the living room. As children, we never were allowed to go in the parlor, especially during the week. It had to be clean in case the minister came. What other people? My grandmother was like a midwife—and, I guess, I dunno, like a substitute doctor or something? Because people would come to her with ailments and sores, you know, whatever. And I remember how my uncle would put her on the back of a tractor and take her out in the field and she would come back with herbs that she would boil. And she was greatly respected.

JAYSON: I love this! Part of the reason why I was excited about doing this interview with you, Amirio, was because of something that Beronda Montgomery—someone else who you might want to interview—said. I had Dr. Montgomery come and talk to my students a couple weeks ago and she said, When I’m interviewing my aunties, I make sure my little cousins are in the room. When I ask my auntie questions, they tell me different things than they will when there are younger people around. And you’ve never said that, Nana—you never mentioned your grandmother going out and getting herbs.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Listen to this one: my sister became very ill (JAYSON: Aunt Shirley!), and my grandmother couldn’t do anything. And they took my sister to the doctor in town, and she wasn’t getting any better. And my grandmother told my uncle, Take me out to the woods, and if this doesn’t work, then we’re going to have to tell her mother. He took her out in the woods, and I remember how she made paste. To this day, I don’t know what was wrong with my sister.

AMIRIO: I’m wondering, being in that kind of environment, how did that shape you in terms of your ideas around healing, your ideas around community? How did that environment shape who you are?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Who I am today? Oh, let me tell you: I love taking care of people. I love helping people. And it’s because of being around people. My mother became a nurse, my sister became a nurse. And although I didn’t follow their careers, I just loved helping people. It’s comforting, it’s satisfying, it’s joy. And I’ve helped a lot of people in my family. I’ve taken care of a lot of people, and it gives me joy.

JAYSON: Do you feel like you learned that appreciation and love for taking care of others from your grandmother and seeing her? You started with talking about your grandmother and then your own mother and your sister both becoming nurses and taking care of people.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: No, I just believe in do unto others that you’d have ‘em do unto you.

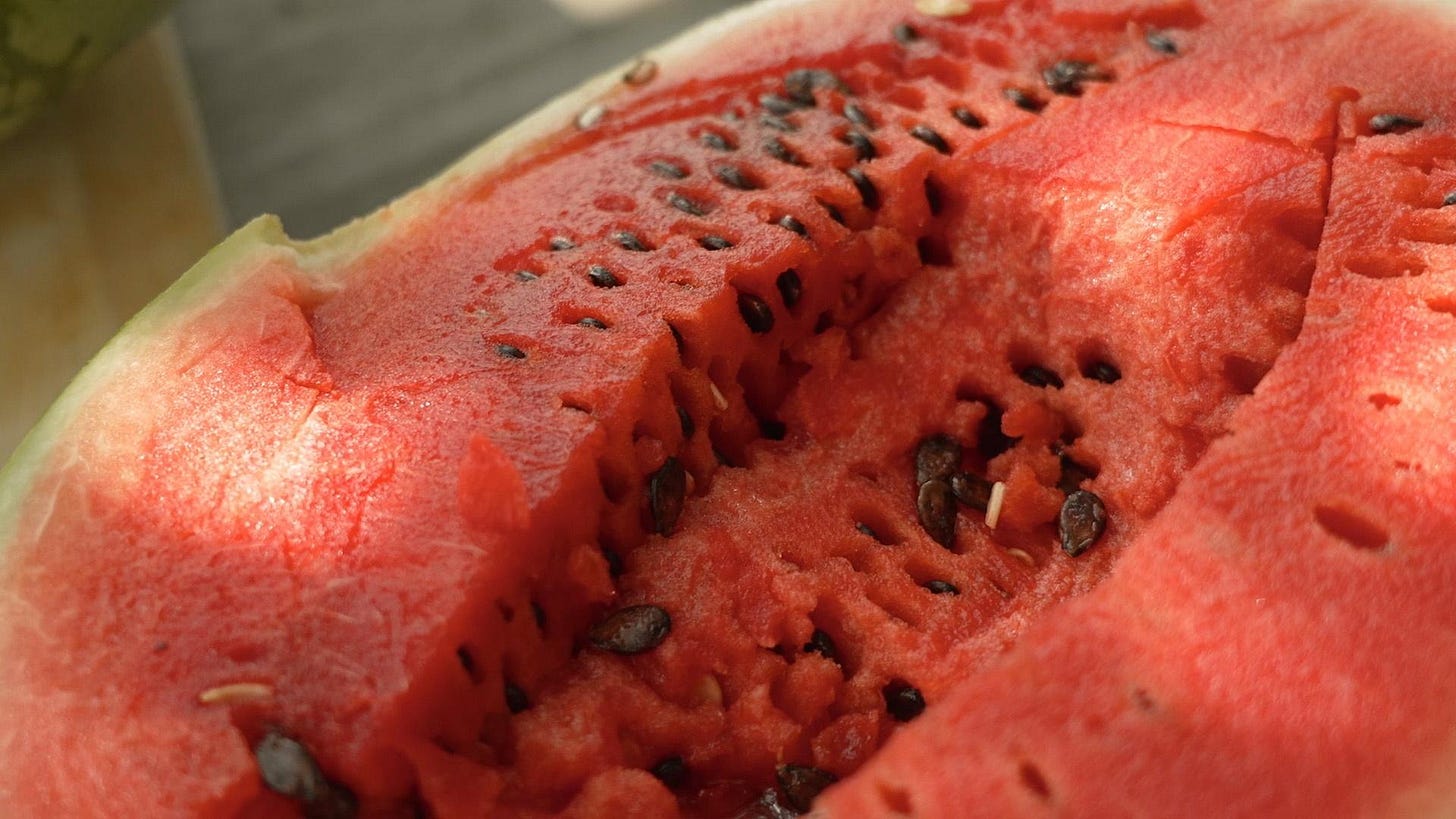

JAYSON: Back to Snow Hill real quick: I just want to ask one more follow-up question about smell. One smell that I remember from Snow Hill was rotten watermelon. (MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Really?) I remember once, Grandma, your mom busted open a watermelon that was rotten and it smelled terrible. It smelled like rotten flesh. (MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Oh, shit.) Do you remember any smells?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Now, I love the smell of a good watermelon. My family had a 300-and-something-acre farm. And so, they produced vegetables and et cetera for the town. And we would go out in the morning—and it would be early in the morning. You’d be out in the field at like four or five o’clock in the morning because you got to get these trucks loaded, and you’d take a watermelon, pick it up, and do like this. (gestures) God, it’s the best smell. Whew!

AMIRIO: Can you describe the smell?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Well, it was a smell of its own. You’d know it anywhere. It was a nice, clean smell, but you knew that it belonged to this object right here. Nothing else smells like it but this, you know? And then we would split it—split it and give whatever and eat out of it. Just dig your hand in first thing in the morning—and it’s cold. Whew!

AMIRIO: I’m thinking more about healing and our relationship to the more-than-human world. I’m wondering for you, Jayson, how have you learned about healing through your sojourns across the country? What’s coming up for you regarding how the natural world has been a teacher when it comes to that?

JAYSON: High school wasn’t the greatest: got into a bad car accident, lost a friend, got jumped, had to get a whole bunch of facial reconstructive surgery. I wasn’t from Mississippi: I moved around, and I was only in Mississippi for about a year before all of this happened. And I don’t know what possessed me to stay, but I’m very glad that I did.

Staying was connected to things like food justice work and landscaping. I can’t tell you how many houses I landscaped in Jackson, Mississippi. Probably at least 20. How many houses I’ve helped build? Probably at least 40. And it was using my hands in community with people that helped me rebuild myself and find my own place and see where I was good at. I’ve always been a communicator, talker, but this was a quiet time when I learned how to listen.

Plants played a pretty important role for me. One of the first projects I was part of was building these large art installations in places of historical trauma to create new memories in those spaces. And one of the things that we did was build these installations using invasive materials. So, we used kudzu and bamboo and other invasives in Mississippi to build these spaces. Invasives are a reminder to move away from our impulse to eradicate and think about building with what we have, where we are, which is oftentimes the work of caregiving. Thinking from the environmentalist perspective, with justice in mind, dealing with invasives, moving forward, is something that requires more than eradication; you can read Yota Batsaki and learn it requires building with what you have.

It took me a while to really get into plants, in particular. One of the things I always heard in Jackson was, Honestly, niggas is hungry. I was a philosophy and environmental science major. One of the first things I studied was Ethiopia and water because I thought Ethiopia and Egypt were gonna go to war. This was back in 2010. Remember I saved up all that money to go to Ethiopia, and I was learning how to build those water heaters? I would bring up what was happening: Because the British said that Egypt’s the gift of the Nile, Egypt gets to use the water, and they get to circumvent international law and keep Ethiopia from protecting their people—even bringing that type of justice component into a Mississippi context, folks was just like, But, like, you got 15 vacant houses across the street from me. So, that’s what really got me into food work.

AMIRIO: You both have talked about moving through these landscapes, and I’m thinking about, from the land’s perspective, the palimpsests that the landscapes hold—all the memories there. I wonder if you could say more about that. What does it mean to work with all the different narratives of all these different places?

JAYSON: I was in a conversation with Abra Lee recently (she’s another person you should reach out to!). And she dropped this Leah Penniman line about land not being the criminal, but the scene of the crime.4 And that’s something I’ve been thinking a bit about recently. I’m trying to think of how I want to address this question because, from a practitioner’s point of view, I’m still thinking about the people in these places and really connecting them.

Not trying to take the land as like this kind of blank canvas that doesn’t have its differences, but one of the things that you see oftentimes, in terms of the history of Black land efforts, is that land isn’t enough. Land doesn’t protect us; having land has never protected us. It’s always been something that people can take away. Even in a place like Philadelphia—Philadelphia has an urban agriculture director, Ash Richards. And even still, according to Philly farmer Lex Wiley, one of the major fears that a lot of the gardeners and urban farmers here in Philly have is land security, is holding onto the land. We have personal, personal history in our family of not being able to hold onto land for an assortment of different reasons. And it’s a tough thing. Our elders and our ancestors did what they could with what they had.

In terms of what land holds on to, I’ve been thinking a little bit about this. You have places like, let’s say, Chicago or New York. These places, long before they had tall buildings and white folks, were centers where Indigenous communities from hundreds of miles away would come together and trade. That was because of the waterways, the fertility of the land, maybe the migratory birds, I don’t know. Centers of commerce oftentimes are built on centers of commerce, and they still end up being these trading spaces to which people gravitate. And I think very similarly about places of trauma and violence. You think about Louisiana’s Cancer Alley5—places where there used to be plantations and now have petrochemicals and prisons. Places where people are enslaved and then were sharecroppers who were then pushed off their land by the KKK and other organized crime that’s more de jure.

It’s a spiritual thing, too. Land isn’t enough. We always have to have some type of personal faith situation or in good faith situation. I’m thinking about something that my Uncle Lefty said once when I asked him, Hey, what would you tell young Black folks who are trying to reconnect with land? And he said, Don’t forget about God. Ain’t no white people gave us this land. This land is God. And he said, Your first ancestor, who was one of the first Black people to own land in Maryland, was able to turn that land into something for his family—not because it was a gift from anybody, but because he had faith that the rains would come, and that the seeds would work, and that he had the wherewithal to do it.

So, there’s a faith and a spirituality that needs to be coupled with land. And I fear oftentimes that the way it’s talked about—it can be so essentialist. It’s like, The land is the thing! But when you look everywhere, be it southern Mexico or the Pacific coast of Colombia—they’ve recently extended so many rights to land, to these Black communities who were able to get land because of their ancestral relations with these waterways, and their ancestral and ecological knowledge of the tides and the mangroves and the oysters. But in a very neoliberal way, the state has extended them individual stewardship over the places while leaving them, in some ways, forced to protect these ecosystems without the support of the government in ways that’s lent itself for other companies or even organized crime to come in and displace communities from land. So, in many different circumstances, you see land just isn’t enough. That’s a reminder I have from my own family experience. Also, the land that’s been extended to us is oftentimes not the best. We’ve always figured out how to grow on land that has toxins, doesn’t have water; land that doesn’t have great soil. Land is so essential, but it’s always a reminder of what we ought to bring to the table—and what we always have.

AMIRIO: Jayson, you’re starting to dive into these broader, more diverse environmental histories, so let’s pivot in that direction. What I love so much about your work is that you’re deep in so many archives and, beautifully, cohesively, creating these narratives for us to be in the archives with you, to understand these broader histories that feel siloed but are often so interconnected.

I’m wondering for you, what specifically Black botanical or broader environmental histories are we not talking about enough, that we may be losing a certain reverence for? And on the flip side, are there commonly understood histories that you feel are misremembered or misrepresented? I think about George Washington Carver, for example, who was deemed “the peanut guy”6—and that’s kind of it. But, there’s so much more there in his story that’s juicy and beautiful.

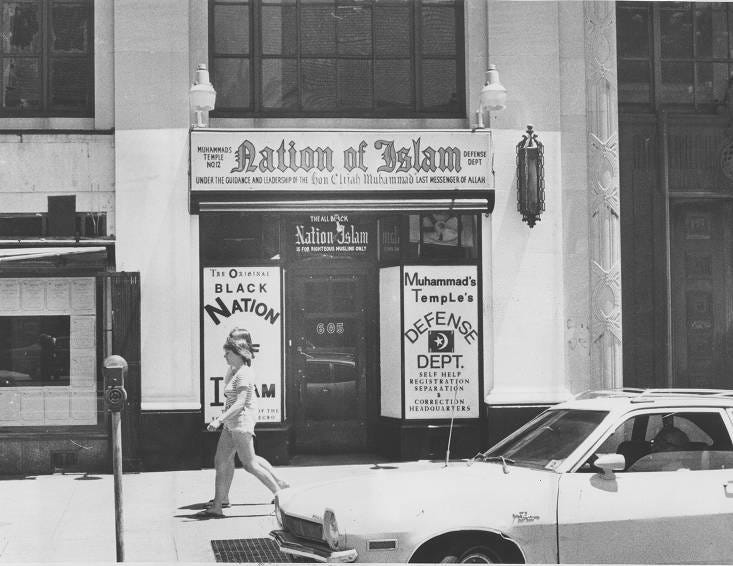

And thinking about these broader, Black histories, Mrs. Scott, I know that Jayson shared that at one point you were involved with the Nation of Islam—a group that is so representative of a very specific moment in Black history that still has an ongoing impact. I’m wondering, thinking about your involvement, were there conversations about how the Nation could be involved with environmental activism or stewardship? What was the relationship between this group and thinking about the environment?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I was in the Nation of Islam. I was not as active. I had small children. Well, I had babies. Sometimes, I think about friends who were involved at the same time that I was, and they seem to still be at this stage in their life—they’re active and they’re doing and they’re growing. I just was not that involved, although I believed in it. And so, I really don’t have that much input. My husband was very involved, other members of my family, but I was not—I didn’t go out. That was it. I didn’t go out like others did. I had my mother in the house, too; I couldn’t leave my mother. And I had children, small children. But, if you have a question, I’ll try to answer. It was not like I didn’t know nothing. (laughs)

AMIRIO: Within the Nation, were there conversations about how this group could be involved with different environmental causes, like those related to pollution in Philadelphia, for example? Were you privy to anything like that?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: They were very, very, very involved in raising fruits and vegetables. They had a humongous farm down South. It must have been really humongous because they would distribute to other states—up here in the North. But, I don’t really know that much. And I would doubt that there would be many or any Sisters who could answer that question because they were not involved.

JAYSON: The men dominated?

MRS. SCOTT: Yeah, that’s it!

AMIRIO: Something else that Jayson mentioned in one of our preparation calls is that you had your own tree-cutting business in Philadelphia after your time in the Nation. Could you say more about this tree-cutting business? How did you start that? What was the name of it? What was the day-to-day of owning a business like that in Philly?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Michael, who was my nephew—but my husband and I raised him along with my son. And actually, they were almost the same age. Micheal was in the service and he got hurt and he came home and he had nothing to do. So he started cutting grass—lawns. Then, during my son Accem’s last year in school at Michigan State, he came home to help Michael. And, God, between the two of them, I don’t know how they got together and decided what they were going to do and how they were going to do it and how we going to get a truck. And I’m saying, Who’s going to drive the truck, how they going to learn, how they going to do this? And I tell you, we became so well-known in Philly and started working outside of Philly. Those boys, I tell you! And God, I forgot the name of the business—it’s been so long.

But anyway, there was an organization that helped us. Well-known. I can’t think of the name, but they decided to take us on as a minority business.

JAYSON: They were a major firm.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Yeah! This thing about helping minorities—that was just coming alive here in Philly. And so they took us on, and we got three trucks and our office here in the city. And we were doing well. But there was a whole lot of unfair things that happened, of course. And after a while, my boys just said, Enough is enough.

Aspen! That was the name of the company.

JAYSON: They gave y’all contracts so long as they could get a lil’ piece. But you ended up staying on—you were there for a long time.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I did, I did, yeah.

AMIRIO: Do you know around when you all started and around when you all sunsetted?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Oh, God. I can’t remember that. You think I can remember that? (laughs)

JAYSON: I feel like I was little because I remember having to go in the office with you.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Oh, yes!

JAYSON: So, probably, you were still going until 2002, 2003.

MRS. SCOTT: Yeah, something like that.

JAYSON: When did you start? Probably in the 80s, right?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Yeah, the late 80s.

JAYSON: Late 80s? For about 20 years.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: It was a while, yeah.

AMIRIO: When you zip around Philly, do you see the impact of the work that your company was doing?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I don’t. And the company that I worked for, the company who was helping minorities—we being one of them—I don’t even see their trucks anymore. And they had been around for years and years. But I never see them. I have gone to other cities and seen their trucks. That’s how they develop their organization. If I don’t see ‘em, you could go to places like Jersey. I can’t remember the places I’ve gone outside of Philadelphia and New Jersey and seen their trucks.

As minorities working, we had our own truck, our own calls. Some of the jobs we got was because we were connected with Aspen. So, we did the East Coast—minority workers were East Coast under Aspen—and they profited from that. After a while, you get tired of that crap.

AMIRIO: Do you remember some of the work that was happening? Of course, you all were dealing with trees, but do you remember different things that y’all were looking out for? Were you really concerned with a tree’s health, or were many of these jobs more aesthetic—We just want this tree gone because it looks better? Do you remember the day-to-day?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Our work was to take a tree down when there was storms—and we used to have really bad storms. We would go wherever. The boys became really good at this because a storm would come and take the electric cords—electric wires—down. You have to be so careful. And boy, they became so good. I’m just so proud of the work that they did. We became the “ethnic group” for the East Coast. And I say that because you’d see white people—more of them than us. But we would be the first ones to go.

AMIRIO: I wonder for you, Jayson, going back to one of the earlier questions about broader Black botanical histories that we’re not talking about enough, that we’re forgetting or misremembering—what’s coming up for you in terms of that?

JAYSON: I’m particularly fascinated with sesame seeds because they were so important in the diasporic experience for people of African descent in the Americas. It’s debated as to whether or not it was domesticated, or if a variety was domesticated, in West Africa. I’m not a police officer, so I’m not in the business of looking for smoking guns. So that type of question—Where was it domesticated?—doesn’t matter to me as much as the seed having a long history and touching a lot of people.

It’s undeniable that it’s had 5,000 years of history in West Africa and that it was essential. It was the way Black folks lit up their homes. Enslaved Black folks in cabins were able to have some illumination at night. Sesame seeds were what Black folks mixed into their rations of “Indian corn” so they could have more substance and more fat in what they ate.

I would even say that if you look at a lot of historical records, it seems that sesame seeds, particularly in places like South Carolina, provided one of the few markets where Black women, in particular, could use their skills in the kitchen to sell products. There were a lot of boats where you had Black women—they were called derogatory names like “mammy”—who would sell benne7 seed cakes or benne candy. I found some records that show, as early as the 1890s, after enslavement, there were kids across the East who knew about these benne candies that were all being produced by Black women. So, similar to folks like Abra Lee writing about how flowers in Florida were one of the first things that Black women sold to become really wealthy in certain places—similarly, sesame is also one of those things that Black folks used.

When planters first figured out how to crush cottonseeds to make oil for an assortment of different things, they also were crushing sesame seeds. So, if you look at records, it’s crazy to see how many observers you had on plantations watching Black folks use sesame seeds. They figured out, Oh, it could be used for this medicine, or it could be used for this, that, and the third. And because it has that mucusy, cooling sensation, similar to okra or even cotton, there were a lot of people who associated it with cooling properties. If you had summer illness, you’d be rubbed with sesame leaves. There’s a lot of old botanical and medical journals that speak to the qualities of sesame.

Even Thomas Jefferson watched his enslaved people grow sesame. As colonists were trying to move away from importing things like tea and olive oil, they were looking to their Black populations and saying things like, Sesame is one of the greatest gifts given to the Americas. And they were even acknowledging that sesame was brought by West Africans. So, there’s a lot of work to be done with sesame, because it’s one of those things that we oftentimes associate with the Middle East or Mediterranean spaces or East Asian spaces. But, there’s very few communities of people of African descent in the diaspora that don’t have recipes with sesame in them.

AMIRIO: Based on your work, what do you think has happened between then and now that has created a huge forgetting of such a robust archive? And I’m also wondering, vis-a-vis that archive, what you make of this current moment within the wellness industry of antagonism toward different seed oils, sesame oil included?

JAYSON: I love that last question! I honestly am not the best person to ask; someone who you might reach out to is Pilar Egüez Guevara, who writes about Afro-Ecuadorian coconut growers in Esmeraldas, and particularly looks at this moment in 2015. She has a beautiful documentary called Raspando coco (or Scraping coco).

An organization that tracks cardiovascular health made a statement in 2015 about how coconut oil and its saturated fats are bad. And every few months, there’s new studies that say, Oh no, this is the one, this is the bad one. And that has a complete adverse effect on people. I would argue that, in many ways, the interchangeability of seeds and seed oils creates a type of interchangeability of the seed oil makers. When you read those labels that say “this product may contain cottonseed, sesame seed oil, palm oil, coconuts”—it’s literally saying that it really doesn’t matter which one of these ingredients the product uses, it doesn’t matter which community we’re depending on, because we have the science and the technology to extract what we want from what we have, as long we can get the lowest price. The current interchangeability and fungibility of seed oils in products is at the highest rate we’ve ever seen. It renders these oils interchangeable, it renders people disposable. That’s something that you see, regardless of the messaging; that is part of the undercurrent. Because all of these seed oils become subsumed under these types of triglycerides that industries can manipulate in shape, regardless of whether or not they’re making a soap or processed food or a textile. There’s a violence there, for sure. I forgot the first part of the question!

AMIRIO: I was wondering about the machinations that made us forget sesame having such an extensive, rich history, specifically among Black people.

JAYSON: How does that gap come into play? That’s a tough question.

AMIRIO: There could be a million reasons for this, but for you, what coalescence of different phenomena has happened? What do you think is the overarching headline for why we’ve forgotten sesame?

JAYSON: Yeah, that’s a good question. That’s what scholars like Londa Schiebinger call an agnotological question. Agnotology is the study of ignorance. How do we understand how the ignorance is formed or how these blind spots are made? One starts super, super early.

From the jump, sesame was considered really profitable. We’re talking 18th century, early 19th century, right? White folks were saying, Oh, we’ve observed Black folks use sesame for this. But we think, with the “gentleman’s science,” if we bring it into a lab, or if we look at it under a microscope, we can improve it.

Very early on, you had companies that sold sesame ointment, leaves, and seeds as something that helped dysentery. Around 1803, in South Carolina, there was a huge dysentery epidemic, and sesame emerged as this thing that helped. And in that moment it was like, Okay, this is useful. How can we get this into the category of medicine? But by getting sesame into the category of medicine, it was separated from folk science and folklore. The fact that it was profitable from the beginning, you had companies who were selling it and saying that it’s “legit” and it’s “scientific.” Right in that moment, the companies were separating it from the plantation, right? And that’s what happened with a lot of cottonseed oils, too. I’m thinking of Crisco. When Crisco was made in 1911, when it was first synthesized, it had, to date, the largest advertising campaign behind it.

Procter & Gamble came out with Crisco, and they spent about a year and a half trying to figure out how to convince people to eat crystallized cottonseed oil. That’s what Crisco stands for—“crystallized cottonseed oil.” Crisco was made out of one hundred percent cotton until the 80s. So, for 70 years or so, it was made out of cotton. Part of the process was figuring out, How do we sell this as something that was made in a laboratory in places like Cincinnati and Cleveland—and not from Mississippi and Alabama? So, Procter & Gamble spent so much money making these advertisements. “You can have it like your mammy used to make”—but it would be this white woman. The company spent over a million dollars. The biggest advertising campaign for selling a product to that point in human history was for selling cottonseed oil.

Me and a dear geographer—a beautiful soul—Brian Williams wrote an article called “Cotton, Whiteness, and Other Poisons.” We were going to name it “Eating (Jim) Crow” because what we were going to argue was that through the production of Crisco, Procter & Gamble was trying to maintain the political economy of the Jim Crow South. Because cotton prices were dwindling due to competition, how do you keep cotton profitable? How can you diversify all of its avenues so you can maintain that power?

Ultimately, the industries won out over the planters, so the planters ate crow. So, there’s the double entendre: the fact that working with cotton maintained Jim Crow, but the planters ended up losing out on this venture to northern industrialists. This leads me to another thing I was going to say: the well-known plant that we don’t know very well is cotton.

Cotton is something that everyone thinks they know very well—and it’s the history of Black folks. Yes and no. Fewer people know this history of Crisco, and something that I’m really fascinated with is the history of taking care of cotton. The plant was one of the first plants that set us on this path of this agrochemical modernity that we have today—where we use agrochemicals on everything from maintaining the trees on the sidewalks to the shrubs and the medians to the crops that we eat to the crops that we don’t eat. That all started with cotton. Cotton, one hundred percent, was a major guzzler of arsenic, which was the first major pesticide.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Really?

JAYSON: Oh, one hundred percent. Yeah, it’s not even close! I’m writing on this right now: I’m writing an essay with another beautiful person, Adam Romero, who wrote this great book called Economic Poisoning: Industrial Waste and the Chemicalization of American Agriculture on early histories of pesticides. So, we’re working on this entry for the Oxford environmental bibliography on the rise of pesticides, focused on arsenic. And how arsenic is used is deeply tied to Back folks.

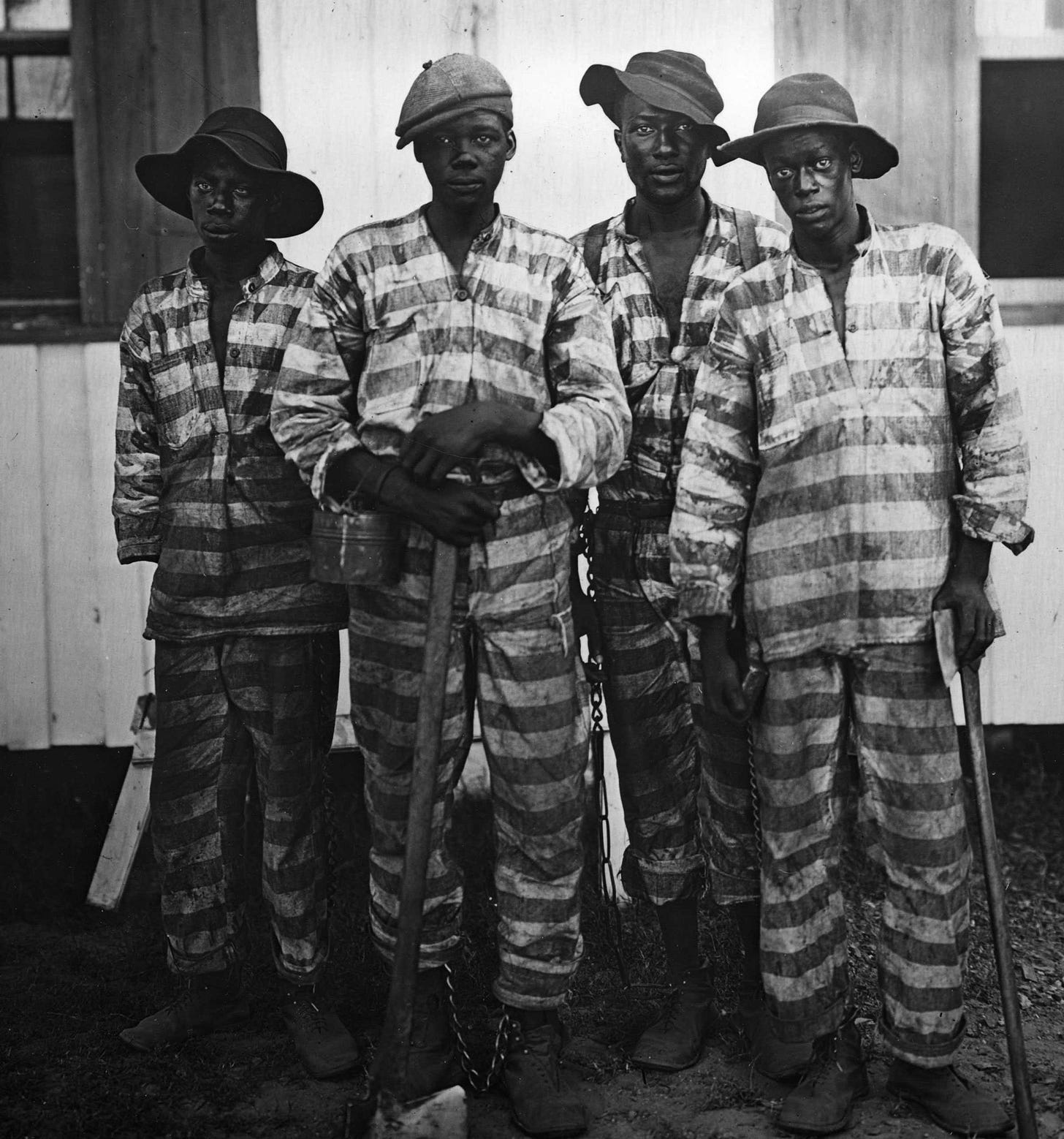

The very first plantations and huge monocultures were vulnerable spaces that attracted these huge pest epidemics. Interestingly enough, one of the first pests that hit cotton was this cotton worm. By eradicating this cotton worm with arsenic, planters actually left the foliage for an even worse cotton crop pest to come in, which was the boll weevil—which eats cotton, not the leaves. Planters, initially, would have Black folks pick the bugs off, and the planters would measure how much time it took for a Black person to pick them off. They’d oftentimes use kids and show them how to mix arsenic with molasses to go and pick the pests off. Then planters started using convict labor. So convict labor was huge for this experiment. The United States Department of Agriculture has a very long history of creating experiments with Black folks, both in prison and free. They have old videos!

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: When I was a kid, on the farm.

JAYSON: Really?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: They would bring imprisoned people out to help work on the farm—with black and white stripes. And when they would come bring ‘em out, they would come out the back—the first person came out the back and then the next one, and they were chained at the ankle, or leg.

JAYSON: And they were picking crops, or were they dealing with insects?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I don’t really know, but I figured it was crops. I dunno. But that makes an impression on a child.

AMIRIO: I was gonna ask you—what did that feel like, seeing those folks?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: It was scary. It was like, You betta watch yourself. That’s how I felt.

JAYSON: You remember seeing the planes drop arsenic, too.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I think it was on the Bane’s farm. The Bane’s farm was next to our farm.

JAYSON: And they had a duster. They had a plane that came and dusted arsenic on their crops.

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I believe it was white powder.

JAYSON: That’s what it would be! It’d either be lead arsenate or calcium arsenate, depending on the plants. But definitely white powder. And what’s interesting is that planters did experiments with this, from 1924 to 1927, give or take. They said, Okay, so one Black person with a mule could dust six to 12 acres at night. They always made Black people do this at night. Always had to do this at night because it’s dust. Usually, when Black people distributed the arsenic by hand, they’d want it to be on to dew so the arsenic stuck better. So, they would do this at night before day. But planters would use that as an argument to pivot to using planes: Well, you could displace 50 to 70 Black dusters per plane.

We talk about how when mechanization and the mechanized harvester came in and basically displaced cotton planters in the 1930s and 1940s, a lot of people had to leave the South—the Great Migration. And a lot of planters said that arsenic was the reason why people left, and the boll weevils. It was too expensive for Black people to have their own farms during these epidemics, so that pushed them out. There are whole books written by white folks on how these pests actually “scared” Black people to the North or how Black folks weren’t intelligent enough to use the arsenic for themselves. So, there was this narrative on who could use early pesticides. Once the planes came, planters literally used language like, You won’t have to feed mules, you won’t have to pay these dusters.

Cotton is one of those plants that shows how the history of the technological advancement of this country has always been connected to the plantation. The plantation has always been one of the first factories or laboratories where scientific advancement took place at the expense of Black folks.

We will never stop studying cotton. There needs to be a project on cotton and climate, because if you go on to a digital archive and type up something like “climate from 1860 to 1910,” I promise you, a third of the results are going to be related to what climates are good for cotton. Some of the earliest climatological data that we have are related to the context of cotton plantations. Those questions that were necessary to thinking about where cotton would grow were some of the first base questions that we were asking in regards to climate. Cotton was one of those things that was everywhere.

AMIRIO: This could have been a whole conversation about cotton!

This is an intergenerational conversation. I’ve already said how much I’m obsessed with this, and I appreciate the generosity of your time and expertise. I want to land on this idea of intergenerational conversations, connecting back to ideas of archives and lineages. Jayson, in an interview with scholar Monica White, you mentioned, “I want to write for my family, I want to write for young and old audiences in an intergenerational way.” There’s something there from a practitioner’s side that I’m really interested in. How has that sort of lens enriched your work? And for folks who want to do that kind of work, what is your practical, grounded advice? What are the pitfalls? What are the actual ways of doing this work? Even the way you explained this richly layered history of cotton—you have a skill that some scholars don’t have in terms of translating the work that they do.

And then, Mrs. Scott, you’ve been so involved in Jayson’s research. You’ve read his work; I've seen photos of you in different educational settings, being a part of his pedagogical process. What has it meant for you to be involved in his practice—to be involved in his research, to be involved in his writing? And how have you been changed by that involvement?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: I’m just a very, very proud grandmother. Don’t start me crying. I’m so proud of him for what he does. I’m also happy that he includes me in so much of what he does.

He has taken me on several trips. Do you want to go to Mexico, Nana? You want to go? To which I’ve said, Yes! He’s just very special in my life. And he’s so knowledgeable about so many things and he takes time; even with me, he takes time. I’m just a proud, proud grandmother. What can I say? And even today, I learned things. I’m not gon’ do nothing with it (laughs), but I’m so glad to hear it, you know what I mean?

When my husband died, Jayson was there, and he came. He was the person who came consistently. He would bring me a plate; it’d be enough for two days. And he called me every day. You don’t expect a young man to do that. And he’s full of energy, trying to make his way in life. I know he’s there for me. Isn’t that special? It’s special. I love him.

AMIRIO: What’s been the most surprising thing you’ve learned from Jayson through his work—and what’s been the most surprising thing you’ve learned about yourself through his work?

MRS. DELORES SCOTT: Oh, well, I don’t know what I’ve learned about myself, but what I do know is that there’ll be something different: When I go places with him, there’s always something new. I could stay home and learn nothin’. But when I’m with him, there’s always something. Isn’t that special?

JAYSON: What that makes me think of is, with oral histories and stuff, we don’t remember everything. The world doesn’t move through truth and facts and things that have been not written down and recorded—especially not for Black folks. Oral history isn’t always something that is ready in the brain to come out when a question is asked. Sometimes, it takes conversation. Sometimes, it takes scratching the head and remembering things. As someone who’s always talked to my grandmother while dealing with a lot of things in my life—once I started talking to her about my research, it was clear to me that she started remembering things about the farm growing up. You can even see it in this conversation: when certain questions were asked, I thought, I have never even heard this. You can bring family history to life. It’s not just a recording. It’s already there. It’s the work of bringing it out; it takes memory work. Not just going in an archive.

Earlier today, we had lunch with Clay Cansler, the editor who helped publish the work about my grandfather, “Fish Hacks.” We talked about how sometimes you got to leave your hunch at the door. Your hunch will take you somewhere, but sometimes you need to drop the hubris of thinking you know and be open to figuring out and realizing that your hunch might get you to the door, but it won’t get you to your destination. Or to where you might want to go because you might not know what the destination is. You have to relinquish yourself of the idea that you know what’s best.

Sometimes with family or oral history, you leave your hunches at the door, and you trust and you have faith that the people who raised you have something to add. I learned that when writing about my grandfather. The piece I wrote about him came out six months after he read it the first time. It came out in November 2023; I think he read it the first time in May of that year. And I’ll never forget—you told me, Nana—that he hadn’t really gotten out of bed for a while. But when you started reading him this, he was like, Hold up. This about me? Hol’ up. I need to get shaved, I need to get cleaned up. I need to read this for myself. And he did that. And after reading he said, I want to go fishing again. It was the first time in a while he had thought about fishing again. So we ended up taking a fishing trip.

The day after my grandfather’s 97th birthday, over 20 family members got on a boat. We had a good time. But that article made family history, you know what I’m saying? And so it’s just a reminder to work with what you have while you have it, because you can make history with your own family through your work.

For me, I slipped and fell into academia. Initially, children pushed me to articulate what I’m thinking in my early 20s working at a children’s museum as a philosophy major. They pushed me to articulate my thinking in different ways: when I have to explain it without jargon, when I can’t use a phrase like “structural racism” to circumvent an explanation. And it’s really through talking with family and talking with other people—talking with young people, who really get it.

The last thing I’ll say, thinking about this, is about intergenerationality: it isn’t just the generations here. It’s modeling future stuff. Like I said earlier, Beronda Montgomery offers a really great reminder about how intergenerationality oftentimes can’t fully just be between you and your family, or you and multiple generations, because oftentimes you need to have a third party in the space, or a younger person in the space. Like you, Amirio, have made this conversation. I’m taking notes. I’m learning things that I didn’t know because you’re in this space. So, it’s not just a conversation between generations; it’s an open conversation. I’m thinking about intergenerational conversations more broadly.

I do think our elders tell stories differently when different people are in the room. And that’s an important bit that we need to take into consideration when we’re doing oral histories. Beronda was like, I go and ask my aunties these questions, and they kind of skirt around a whole bunch of details. But as soon as there’s a 10-year-old in the room, they start opening up. So, there’s a lot of power in thinking about who needs to be in these spaces. Who are the generations we’re speaking to? We’ve talked about your grandmother, we’ve talked about Charles, your great-great-grandfather. Intergenerationality is capacious, to use a J.T. Roane word. (It’s one of his favorites!) (laughs)

AMIRIO: I love that! I want to end thinking about ancestors, thinking about folks who are still yet to come, who aren’t even in this plane yet. I’m wondering for you, Jayson, what is your hope for your work in terms of what it’s doing for folks who are no longer here? On the flip side, what do you hope your work does for folks who have yet to be here, who may encounter your work at some point long after you’re gone?

JAYSON: I got to leave my hunch at the door. A lot of this work is for me. A lot of this work is coming from feeling like, I’m a broken person. I need healing. And there isn’t the healing that I need in certain spaces. I’m in academia, and in order to do the work that I want to do as a practitioner who brings folks together around environmental and climate justice, I need to heal. I need to feel whole or at least more whole. So, a lot of my writing is about trying to express myself, become myself. And as a Black person, as a Black man in particular, people look at you crazy all the time when you try to express yourself—be it in your clothing and your talk and how you move, all of that. So, I just like to play around with how I express sentences and think, What about if I don’t put that point there? What about if I don’t put a comma there? What about if there’s not a verb? What about if I just use a colon? The fact that I’m doing this and editors say that it looks good, and people say it sounds even better—it’s crazy to me. I’m really flexing muscles to become stronger, to feel held and to hold.

There’s a saying my Nana used to say: Don't compare yourself to white men. Because, one, you’re going to be judged differently, and, two, you might be trying to get on level 90, like them, but you could be on level 900. I just do me with care and see what happens. Sitting in front of someone like you who says they admire my work is nothing I would’ve ever expected. So, who am I to just say that I expect this? I’m blown away every day by things that this work brings me. I got to go to Africa three times this year!

AMIRIO: That’s major!

JAYSON: Who am I to say, I hope to go to Africa five times this year? I think it was adrienne maree brown who talked about moving towards the subjunctive change. Instead of saying, I do this for this to change, you think about what type of world would have to exist for capitalism to end or heteropatriarchy to end. It’s moving away from seeing or expecting or even wanting that causality: My work did this. I was in Jackson, Mississippi, in February, and a woman in her twenties came up to me and said, You came to my second-grade class, and I do this now.

AMIRIO: That’s wild!

JAYSON: When I was doing philosophy with children 12, 13 years ago, in her class, I would’ve never imagined that that class would’ve meant anything to her in the future. You know what I’m saying? Who am I to even imagine this would matter? But she ran up to me in a bar and said, Jayson? Porter? Mr. Porter? (Dr. Porter now! (laughs)) So, in a way, I’ve tried to relinquish myself from that type of assumption. Impact happens: I’m moving, I’m touching, I’m feeling, I’m holding. I know there’s impact, but I don’t need to know what the work does. I’m not going to see the end of capitalism, but hopefully we inch forward. We all have to be a little bit more comfortable fighting battles we’re not going to see the end of.

Jayson’s Recommended Resources

Adam Romero, Economic Poisoning: Industrial Waste and the Chemicalization of American Agriculture

Monica White, Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement

Jori Lewis, Slaves for Peanuts: A Story of Conquest, Liberation, and a Crop That Changed History

Tiya Miles, Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dreams of a Free People

Learn More About Jayson’s Work

Quote from an artist statement written by artist Joan Mayfield that I stumbled upon while visiting a gallery in Washington, D.C.

Amirio: While generously editing this missive, dear friend Kate Weiner pointed me to this op-ed on the consequences of “anticipatory obedience” written by M. Gessen.

Quote from Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens

Quote from a Food & Wine interview with Penniman: “And my friend, Chris Bolden Newsome, who's a Black farmer in Philly, put it really well in reflecting on this. He said the land was the scene of the crime. It's where all of the lynchings took place. The wilderness is where they took you to beat you and throw you in the river. And so it makes sense that the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors are still carrying that trauma in their DNA. Actually, there's studies about this, that of course the descendants of enslaved Africans and sharecroppers are going to carry this trauma and have it associated with the land. But then I said to him, the land might have been the scene of the crime, but she was never the criminal. In fact, I think the land was probably, without us even realizing, the source of our strength.”

Amirio: From Human Rights Watch: “Cancer Alley refers to an approximately 85-mile stretch of communities along the banks of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, where communities exist side by side with some 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical operations.”

Amirio: D. Musa Springer has written a wonderful piece that expands our understanding of Carver’s life and work.

“Benne” is a West African word for sesame.

Incredible intergenerational interview, thank you all! So many ideas that moved me, but this line in particular resonated:

"Invasives are a reminder to move away from our impulse to eradicate and think about building with what we have, where we are, which is oftentimes the work of caregiving."

Something about this sentiment feels really timely right now. Thank you.