Welcome back to PLANTCRAFT—a slow newsletter about people and the plants they love.

“Architecture and design carry significant blame for our disconnect with nature, and for maladaptively turning extreme weather into disasters. They must also, of course, be part of our reintegration and resilience.” —Marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson (What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures, p. 91)

We can’t tell the story of design without plants.

Despite efforts to widen the imaginary ontological gap between humans and plants, vegetal forms continue to entrance us, compelling us to live with, live in, and even live as plants through fashion, architecture, and other design disciplines. Botanical beauty has spilled beyond the garden, merging with human bodies on high-fashion runways and the main stage of RuPaul’s Drag Race. On platforms such as Airbnb, architectural innovation, the leisure economy, and capitalism converge to offer opportunities to vacation in a treehouse or eco-lodge. Potted plants, both real and artificial, proliferate on our interior design mood boards and the shelves of home goods stores.

Looking across the design artifacts forged by human hands over time, we find that the materiality of plant life—wood, bamboo, hemp, straw; petals, seeds, fruits, root systems—becomes a tool and interface for facilitating many human impulses: to build and adorn, to alienate and privatize, to revere and impersonate, to consume and hoard, to resist and dream beyond.1

Worsened in part by the fossil fuel-reliant and resource-intensive production of our fashion, furniture, and other goods, we are witnessing dire global warming. Just as we designed our way into worldwide ecosystemic collapse, can we design our way out of it by renewing relationality with the planet?2 The history of design says “yes.” A generative case study is that of the Arts and Crafts Movement—an antagonistic design response to the Industrial Revolution that shored up public reverence for the slow and the earthbound.

Especially to survive in an increasingly inhospitable era of Earth, I’m curious about where humans will take design next—and observe what roles plants will play in our design futures.

In this month’s missive, I survey the past, present, and potential trajectories of botanical influences on human design with guest Evan Collins. Evan is an architect and design archivist based in Hollywood, California. His early research into the ‘Y2K Aesthetic’ beginning in 2014 helped to lay the foundation for the many branching eras studied by CARI [the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute]; he brings expertise particularly in the fields of graphic, industrial, and interior design of the 1970s-2000s. He holds a Bachelors in Architecture from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and a Masters in Architecture from Columbia University.

For this far-ranging conversation, Evan and I connected across coasts. We talked about what aesthetic movements telegraph about our attitudes toward the beyond-human world, the construction of the self through consumerism, and the role of design in navigating a warming planet. Let’s dive in. (This conversation took place in May 2025 and has been edited for length and clarity.)

AMIRIO: I already stated how excited I am for this conversation. Over the past few months, I’ve been trying to untangle the relationship between botanical life—and, more broadly, the more-than-human world—and design alongside culture, commerce, and capitalism.

The more-than-human world has always informed so much of human life, especially our design artifacts, so I’m interested in diving into all these overlaps and entanglements with you. I want to start by thinking about young Evan encountering all these design artifacts around us, from architecture to interiors to fashion. What were some of the first design artifacts inspired by nature that really moved you or resonated with you as a young person?

EVAN: I mainly grew up outside Washington, D.C., in Northern Virginia, in the suburbs. When I remember that period, the environment was a very beautiful natural landscape. That area is set in very lush forests and rolling hills, but the designed landscape and architecture of Northern Virginia had a very poor relationship with the natural surroundings. I remember not much being around that felt like it had any meaningful connection to nature or was inspired by it. The design and architecture in that area were all very traditionalist, and there were cold, steel office buildings and over-the-top McMansions.

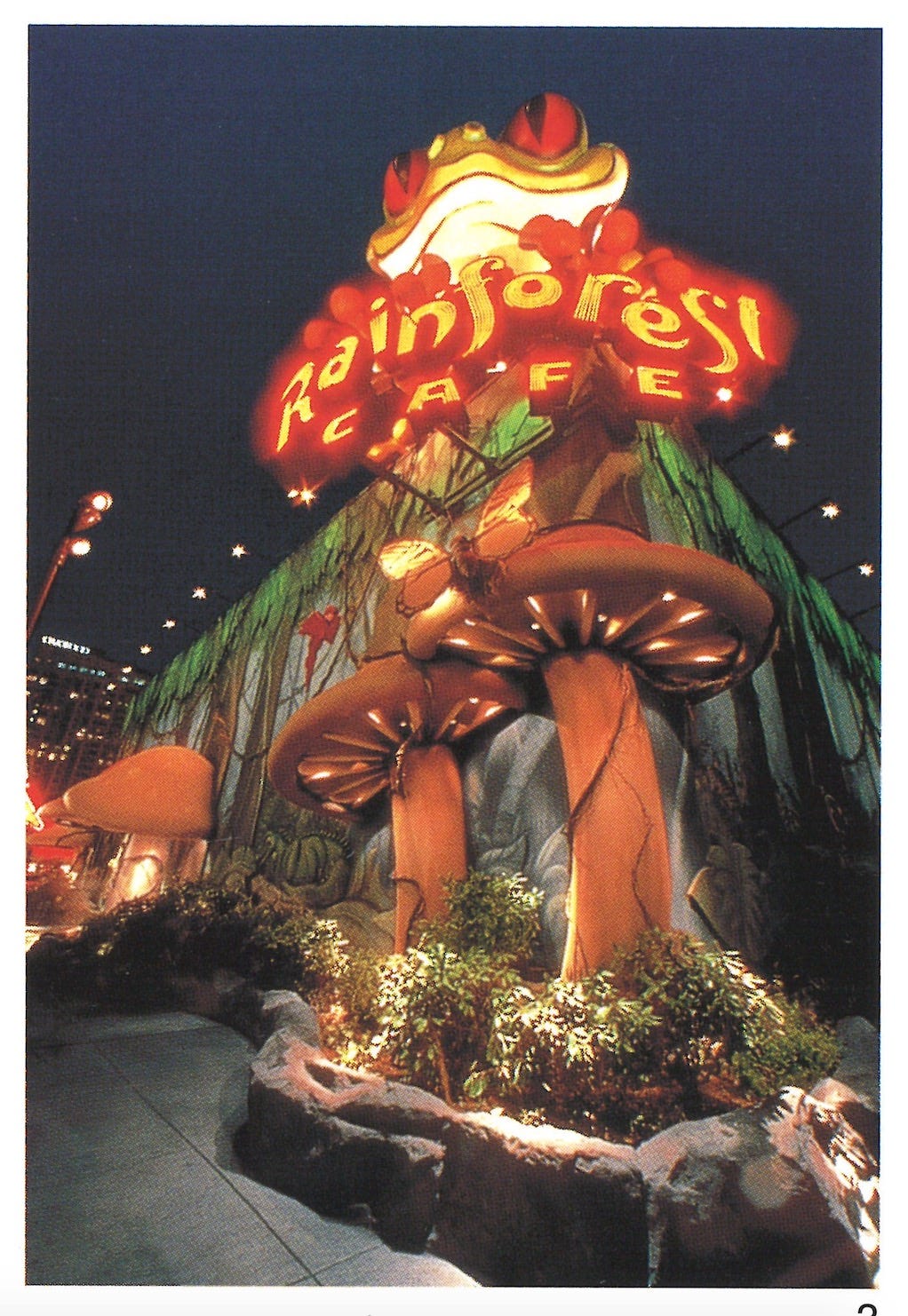

I’m trying to think back to any nature-inspired design from that time. A lot of it was themed design—over-the-top Rainforest Cafe-type design of the 90s, which we call Rainforest Chic. The idea of using nature as a theme or as a means to portray an eco-minded appearance was often in service of selling things. It’s still in service of capitalism and consumerism. So, I do remember spaces I encountered, like Rainforest Cafe—but they were always in a commercial context and were always a fabricated version of nature. There wasn’t an authentic relationship between nature and the built environment.

I also remember seeing what we call Zen-X3, which is an aesthetic you’d find in hair salons or if you went to a spa. Zen-X is a bit culturally appropriative of Japanese design, and it was the closest I would get to a naturalistic space. You’d find pebbles in a fountain with bamboo shoots. Again, everything felt sort of artificial in terms of the aesthetic’s actual relationship to the natural environment. There was a very harsh delineation between indoors and outdoors.

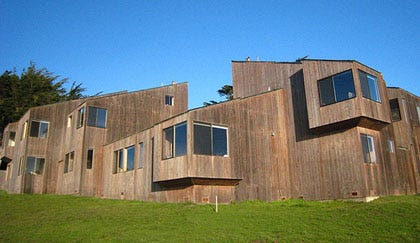

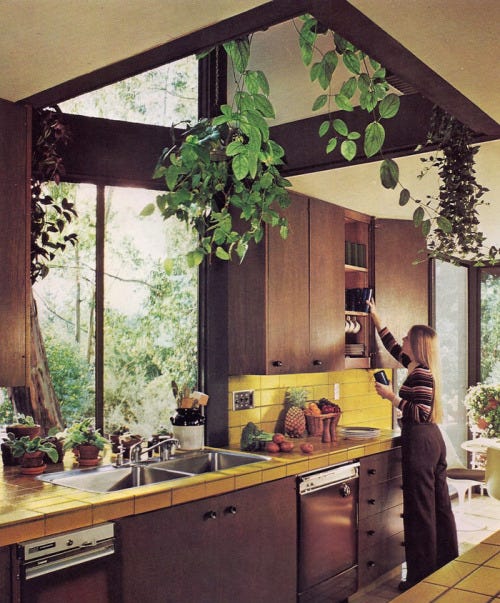

Again, I grew up in the suburbs, in Fairfax County. There, in the mid-century period through the 70s into the early 80s, there were these houses that used what’s called Shed Style.4 The aesthetic was based on the Sea Ranch architecture that developed in California in the 1960s and 70s. Shed Style was part of the environmental movement of the 70s, and you had all these houses adopting that look that dotted the landscape. Some of my friends lived in them. So, those are also some of my earliest memories of more nature-oriented spaces. There would be houses that were clad in wood, very angular, and attempting a more harmonious relationship with the natural environment.

Across from a shopping center that I grew up going to all the time, there was a school that was built into the earth—it was half-underground. It was called Terra Centre Elementary School.5 It had remnants of the 70s. You could tell that at some point there was more of a progressive feeling or movement in Northern Virginia that was leading people to build and attempt to design architecture that had a more integrated relationship with the landscape and the natural environment. By the time I was growing up in the 90s, that was gone. It was all about Chevy SUVs and big colonial McMansions, with no care or consideration towards the environment.

I also remember a style we call Fruitger Aero,6 which has a lot of issues with greenwashing. I remember that aesthetic being hugely integrated with the rise of frozen yogurt shops through interior design. In particular, I noticed that those spaces would always have these specific chairs. I don’t know exactly if designers were trying to go for a sort of naturalistic thing, but the chairs would often have these patterns on them that would have flowery vector images, or what we call Voronoi patterns—which are related to the growth patterns of plants. That was one of the things I noticed in terms of biomorphic design as a teenager, even before I went to architecture school.

One of my most intense experiences with growing up and becoming aware of biomorphic or nature-inspired designs was when I went to undergrad for architecture in 2008. It was huge at the time—this idea of integrating technology with nature. We got really into what were called parametric designs, which are designs created by CAD, or computer-aided design, software that could mimic natural patterns. We’d integrate the designs into architecture projects that I was doing in school. That was my biggest exposure to that at the time, back in the late 2000s. It was a huge movement at the time, and I think it’s influenced design to this day.

AMIRIO: You’re giving me so many threads to pull at! Firstly, I have to say that I love a fellow Virginia Boy. I grew up in Southeastern Virginia, in the Hampton Roads, Tidewater area. Growing up, my peers and I always envisioned NOVA, Northern Virginia, as an upper-middle-class, wealthy area connected to government, corporate life, and business. It’s interesting that our perceptions mirrored the actual architecture of NOVA. I’m also thinking about how upper-middle-class, wealthy people will turn the environment into a luxury. Nature becomes a setting that you can manufacture and go to—but not really settle into. I’d love your thoughts on how “the haves” turn the beyond-human world into a designable product.

I also want to learn more about your college period of becoming aware of biomorphic design. I feel like something was happening in design around the 2008-to-early-2010s era. For example, I’m thinking about fashion designer Lee McQueen when he was still alive. The last collections he designed came out in this period and were very much nature-inspired. I also wonder if you can speak to that era and what was going on that spurred optimism around the relationship between technology, humans, and ecology.

EVAN: Yeah, I’ll say that what you mentioned about nature as a luxury—that’s very true. Growing up, nature felt like a luxury commodity that could be used. There wasn’t an actual care for the environment. Nature was regarded as just something to be molded. It could be controlled and shifted to be whatever people wanted. It’s the idea that nature is, for example, just a giant park that you can design. Nature can be transformed into golf courses or manipulated to look like whatever. There wasn’t a healthy relationship to nature. There were more so questions about how it could be used. There was more emphasis on appearances as opposed to integrating our designed landscape with nature.

I think about the constant suburban growth at that time: the tearing down of forests, clear-cutting everything and replacing it with huge subdivisions and big retention ponds. It was a very commercialized and capitalistic relationship with the environment.

Thinking about your other question, CARI’s research shows how a pendulum swings back and forth—between the rise of environmental movements and their decline. That’s something that I see show up, and it does seem cyclical, at least in the period CARI studies. You had the late 60s and 70s, when we experienced a wave of environmentalism and the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency and the passing of Clean Air Acts. All that influences what I was talking about earlier, with seeing reverberations in housing and eco-school designs in the 70s in Northern Virginia. Then, that declined in the 80s with Reagan and that conservative movement. Ecological concern disappears in this era, which is reflected in the popular and consumer design styles of the time—when you completely lose any sort of relationship to natural or biomorphic design. It completely disappears. It’s all about luxury status and these very clean, sleek designs. Even Memphis design7 had basically no integration with nature and was completely artificial. And then, in the 90s, you had this huge shift back towards environmentalism. It’s another wave, and I’ve just noticed it in the materials that we study.

I go back to these old design magazines, and there’ll be features from 1990 or 1989. In the magazines, it sounds like people are super guilty. It’s like Boomer guilt for the 80s or something about the way that they were acting—the excess and overconsumption and lack of care for the environment. The 90s shift leads to this new, huge wave of styles like Global Village Coffeehouse and what we call Eco-Beige or Eco-Rustic. This wave influences design—but a lot of it is just lip service through design and not about actual fundamental changes to how we interact with the environment. But then all that peters out around the late 90s and the 2000s. Then you get McMansions and Hummers.

The first time I was really conscious of what was happening was when the 2000s went on, and you could see this new wave of resurgent interest in environmentalism bubbling up. You get the “going green” movement, everything gets more eco-oriented. I started noticing it around 2006, 2007. You get a lot of fatigue with the Bush administration. Everybody wants to be more considerate of the environment. And you have this huge wave of rapidly advancing CAD happening simultaneously.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, right before, you see the rise of Y2K Futurism.8 That style is like a proto-version of what would become Frutiger Aero—but a version that is extremely divorced from nature. Y2K Futurism is totally about bubbles and plastic9—and at the same time, it has some influence from naturalistic design and organic flow, movement, and forms. As the 2000s went on, you saw a lot more interest in combining computer design tools with biomorphic ideas of pattern and form; incorporating more naturalistic materials like woods, greenery, and colors inspired by nature; and trying to make design more sustainable. That’s when sustainability in architecture and design, I feel like, really took off. It even went beyond architecture and design, extending into furniture and fashion. Even in graphic design, we saw the growth of what we call Vectorbloom.10

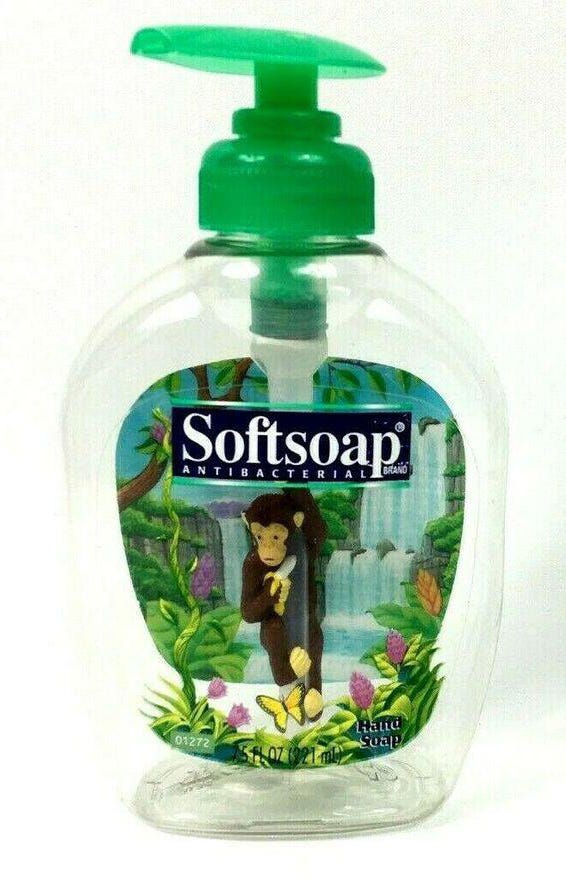

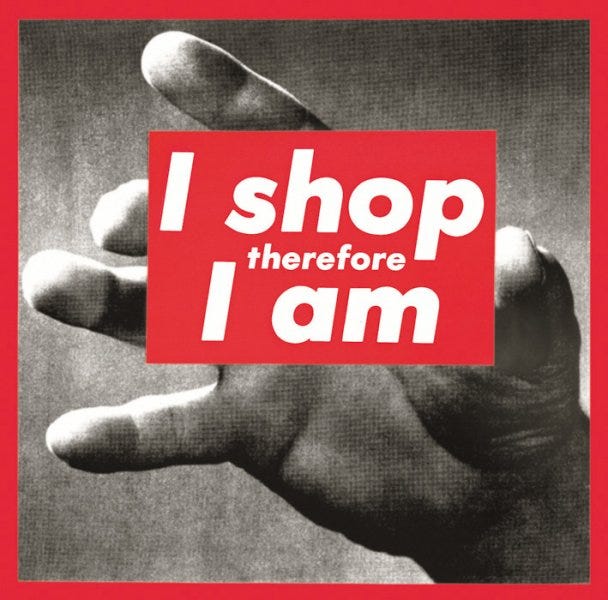

Vectorbloom is influenced by psychedelia, and it uses floral and natural patterns and incorporates them into all sorts of designs. In a sense, it’s greenwashy, because it’s like taking a chair and then slapping a flowery vector pattern on it and saying, Oh, here’s our new eco-collection, or something like that. That’s a huge constant in our CARI research: how capitalism and consumerism will take movements and then, for lack of a better word, neuter them down to something that can be consumed. And then suddenly, you can have your identity built around being sustainable and eco-friendly, but, in reality, nothing’s really fundamentally shifting or changing enough to make a real difference, fight climate change, or have a more harmonious relationship with nature.

AMIRIO: I want to take a step back and introduce CARI, which is the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute.11 The platform describes itself as “a collective association of researchers and designers dedicated to carrying on the important work of categorizing ‘consumer aesthetics’ from the late mid-century.” Why is researching aesthetics—whether Eco-Beige or Y2K Futurism or Indie Sleaze or Vaporwave—necessary, especially for helping us further understand our ever-evolving relationship with the more-than-human world?

EVAN: We try to keep our focus on the late 60s to the present. Our research tries to answer the question of, What’s the story of our culture, society, and economy? We’re telling those stories through looking at our cultural and commercial production over time. Being able to see what society has produced is such an intensely valuable reflection of past zeitgeists and what people were feeling or thinking during a particular period.

I think of archeologists going through ancient societies and trying to figure out what was happening. They look at human production: what did humans create? The pottery, architecture, and other things they can find tell the story of what was going on in a specific society. And that is valuable today.

When I think about this work from a global perspective, I end up with a cynical viewpoint. When looking back at the past, it feels like there’s this sort of endless cycle that we’re stuck in. There’s a feeling anchored in capitalist realism that makes it seem like we’re stuck in this loop over and over again without making the fundamental changes to society that would be needed to both create a sustainable society that can deal with climate change and our overconsumption and pollution of the environment, and have a much better relationship between humanity and nature. I think there’s been improvements for sure, but it just feels like we’re in a bit of a loop—caught between pendulum swings. We’re still oriented towards consumerism, for example.

There’s this documentary that was really influential on how I think about these topics. It’s called The Century of the Self, which talks about how marketing has become so integrated into our ideas of self, identity, and self-actualization. In the late 70s, there was this big move by companies to have people center their identities around consumption. So, there’d be the Outdoorsy Person who’d buy a Jeep and buy clothing from Eddie Bauer. Companies created these identities for people that sometimes connected with someone’s relationship with nature. But then, of course, it all becomes really cynical—it’s just to sell things. Oh, I’m a person who shops at Whole Foods, and I buy organic stuff and I’ll have my eco-friendly house—it’s all still, on a fundamental level, centered on consumption. That’s a fundamental problem with what we study—getting stuck in that loop over and over again. And that is expressed in different styles throughout time. As I’ve mentioned, some things have improved and we’ve made strides. We’ll see where things go with the current horrible administration. There have been good strides in design and more use of eco-friendly materials with fewer harmful, toxic chemicals. And there is a better practice of using fewer resources in design and architecture.

In the 90s, with Y2K futurism, there was barely any consideration of sustainability. You can see how that’s expressed in the design elements: everything is very plasticy, synthetic, shiny, and metallic. There was a well-known designer named Karim Rashid—and I really love his designs—but he was creating endless plastic stuff. There was no consideration for sustainability. It was a completely disposable culture, and that was the mindset around that period—of endless consumption. I know overconsuming is still a problem for sure, but I feel like there’s been at least somewhat of a move away from that and more of an emphasis on crafting. There’s a movement of people who are crafting pieces to last, going against fast fashion and the fast consumption of furniture that falls apart. That’s where I see some progress.

AMIRIO: I love that you’re naming how, through these artifacts that we’ve made, we’re able to tell so much about the cultural attitudes and prominent ideologies of the past and even present. And there’s also the materiality of what you’re talking about.

As you look at these different design movements, you can think about the materials used. For example, through these visual movements, can we track which countries were being most extracted from because they offered a specific metal or mineral? Can you speak to the materiality of these design movements and what they can tell us, particularly when it comes to our impact on the more-than-human world?

EVAN: As the 80s went on through the early 90s, there was a very conscious shift at the time, which you could see through materiality changes. The early 80s through the mid-80s were so highly focused on extremely synthetic spaces. What’s interesting is the changing relationship to nature, as it shifted away from Eco-Shed12—a style emphasizing lots of wood paneling, macrame hanging plants. In the 70s, we’re seeing the first wave of solar homes. There was more of an attempt to integrate with the natural environment and be more eco-friendly. But then, in the 80s, you see this hard shift towards the main materials of that time period: they’re synthetic, and they’re not rustic in any sense. The materials are marble, gold, and very sleek, shiny metals. And in Memphis design, you get a lot of artificial laminates, plastics, and super-bright artificial colors.

Then you get neon, and you’ll find the only time nature seems to make an appearance is through planters—making nature purely decorative. And then the rise of artificial plants became huge in the 80s—completely, just totally, disregarding any actual natural landscape. Even if there were landscapes inside or around buildings, they were all completely controlled. They were all modified, they weren’t naturalistic. It’s not like now, when we have ideas around xeriscaping or, instead of having a front yard of grass, you have something more naturalistic that grows on its own. The landscapes in the 80s were all very designed and controlled to be in the service giving off a certain appearance, being attractive, and complimenting the other synthetic forms. Think back to the shopping malls of the 80s, which had the exact same style with marble, glass, gold, and steel with plants dotted around just purely for appearance—and they were maybe even fake. Our research shows that there was a huge backlash to that in the late 80s into the early 90s.

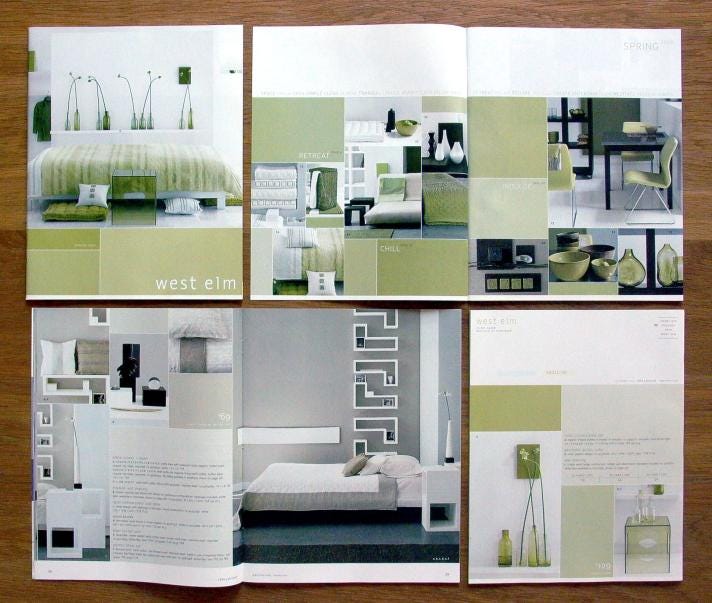

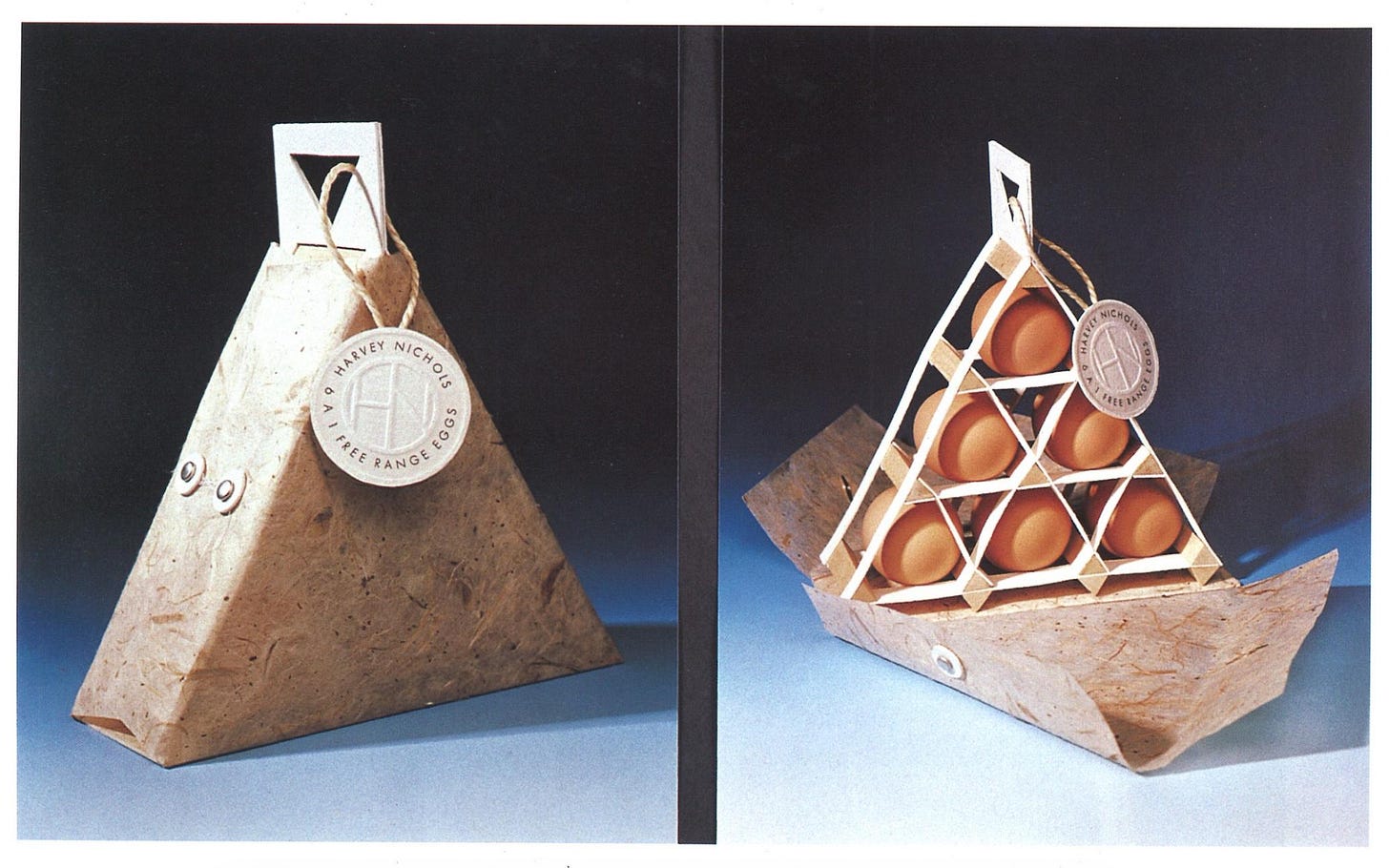

The backlash coincided with either the third-wave or fourth-wave environmental movement. It was a genuine shift, for sure, but it was also very fashionable. At this time, CARI has noticed that interior designers are using wall washes to achieve a naturalistic stucco look, and the materials designers use get more naturalistic—incorporating woods, more irregular forms, and organic elements. This era is when we see what we call Eco-Beige or Eco-Rustic.13 The designs of this time are particularly funny because they now seem to us like transparent greenwashing. But folks in this period got so into it.

One example that’s totally ridiculous from this era is the packaging of single apples. I think it was supposed to be an eco-friendly food thing, but retailers would take one apple, put it in a little bed of straw, tie it up with twine, and put this speckly, recycled paper around it—but for one apple. (laughs) The whole point is retailers shipped out one apple with all this packaging. You could tell that they didn’t know what they were doing, but they were trying to give the appearance of being eco-friendly because that was the cool new thing. It was trendy; it was the new thing to do. It was a way of selling the idea of sustainability as opposed to implementing it. This tactic was everywhere in this time period. I found so many examples of it, and, cynically, maybe there was some good behind it, but it seems like a sales tactic. It’s a great example of the materiality shift between the 80s and 90s.

AMIRIO: I keep thinking about you mentioning greenwashing and how there has been this ongoing trend of real, radical, grassroots organizing, particularly around climate change, being swept up by the forces of commerce and capitalism. Let’s dig into climate change and design.

When preparing for this conversation, I thought about a recent issue of Deem, a design magazine, which framed the climate crisis and its consequences as “the biggest design challenge of all.” What are the opportunities that feel real right now for design to help us have healthier relationships between humans and nature? Also, what have been the biggest failings of design when it comes to challenging ecological devastation? Again, you already mentioned greenwashing, which feels like a colossal failure. With those two threads—opportunities and failings—what’s coming up for you?

EVAN: As I mentioned before, one of the positives I’m seeing is a movement that is focusing on having and creating objects, furniture, and fashion that lasts longer. That’s a huge one that I’m somewhat optimistic about. It’s conflicting because I’ve grown to love some styles from past time periods that I initially hated. The problem is that I recognize many of those styles come from a zeitgeist or society that focused too much on rapid consumption and constantly shifting trends—Oh, let’s redecorate our kitchen every couple of years. Let’s have constantly changing fashion. Those attitudes generated a bunch of really fun stuff to look at retrospectively, but they didn’t foster a sustainable way of living. So, I appreciate the idea of slow movements: slow fashion, slow eating, slow furniture.

Keeping things longer, making better use of vintage furniture and used items. I’ve noticed that the quality of clothing and furniture has declined, as they are often made with planned obsolescence and developed to be constantly consumed and thrown away. Moving away from fast consumption is a good trend that I’m noticing, and it seems like it’s going to be sticking around. That shift is a great opportunity for people to take stock of the immense amount of things that we’ve created and that are already existing. I’ve also noticed the resurgence of maximalist styles. Maximalism can sound like it’s huge on consumption, but it can also be about using what we already have and remixing those items in new ways in interior design and fashion. Additionally, over the past couple of decades in architectural design, new urbanist movements have focused on transit-oriented design and creating mixed-use spaces. Those design approaches support a much healthier way of existing on our planet.

During the time window that CARI studies, there was massive suburban and exurban growth, and a bit of decay in the cities. There has been a shift away from that to having much more consideration for building higher-density areas and incorporating more nature into our designs, like with pocket parks. The shift has also included rethinking about how we’re landscaping and doing design, getting rid of lawns, and using more sustainable materials. That’s a hugely positive thing in our society currently. We’re still building ugly suburban areas, but now it does seem like there is much more of an interest amongst younger folks, and even some of the older generation, in living in environments that have a better, more sustainable relationship with the natural landscape; not converting more land into huge, clear-cut suburban developments; preserving more natural environments; doing a better job of having even the basic elements of construction and design use more sustainable materials; having more passive ways of dealing with ventilation; and using less harmful chemicals and toxic paints. There is a lot that has quietly happened over the past 20 years or so. There has been a great, positive shift toward using more renewable energy. I’m happy to see it, but it’s not moving fast enough to deal with the extremely dire situation that we’re in.

And then, of course, a lot of the negatives are still ongoing, including continued suburbanization—that’s one of the greatest failings of the entire 20th century that has had horrible cultural, social, economic, and environmental ramifications around the world, but especially the United States. And then there’s the continued fast fashion consumption. You see the news about Stanley cups or these TikTok social media trends that overemphasize and are completely centered around consumption. It does seem like culture is starting to shift away from that, but I don’t know. It’s hard to tell sometimes.

AMIRIO: I want to get into a case study of one of the movements that CARI researches—thinking about what the movement is, what the core unifying elements of it are, and what the movement says about the more-human-world economically, socially, and politically. One movement that I’ve really loved thinking about is Global Village Coffeehouse because, on one hand, it feels so nostalgic and, on the other hand, it has all these troubling quirks, like the remixing of natural and colonial-era imagery. There’s so much happening that invokes warmth and comfort for me, but there’s also a lot of flattening and othering of the natural world and communities on the margins. Let’s dive into Global Village Coffeehouse.

EVAN: Global Village Coffeehouse (GVC) is pretty much contemporaneous with Eco-Beige or Eco-Rustic. “Global Village Coffeehouse” is an umbrella term that encompasses a bunch of design things that feel like they are related to each other. It’s a very problematic style, that’s for sure.

Setting the stage for what was going on: you had the fall of the Soviet Union. America becomes the one big global superpower. You have this massive rise in what we now all exist within: globalization. That was huge at the time. From an American, middle-of-the-road viewpoint in the early 90s, that was a purely good thing. They loved it. American leaders were like, Okay, the world’s coming together, and now we’re the lone superpower. America decides we’re going to guide the rest of the world into this new, amazing, globalized millennium.

Those ideas get tied up with capitalism and consumerism and lead to the perspective that we’re now one big global village. Let’s pull from all the cultures that we want and mix those elements up into this giant mess of stuff and then throw it back to sell products to people. There’s this idea that, Oh, we’re all together now. Global Village Coffeehouse completely disregarded all of the historical, terrible things associated with colonialism, the extraction of resources from the Global South—all those horrible things that made the U.S. a global superpower and consumerism hub. Global Village Coffeehouse doesn't interrogate any of those things at all. It’s purely appearance-based and about creating an idealized version of history that gets sold back to people. It’s like, Oh, well, we can all be one globalized world and everyone’s equal—but this design movement wasn’t dealing with any of the real inequities of anything.

Global Village Coffeehouse is rooted in cultural appropriation, exoticism, and even Orientalism. From what I can tell, it pulls from Indigenous artwork, Aztec and African art. It pulls from everything, all at one time, and mixes it up into this giant melange of styles that get carelessly mixed together to create this vague idea of being connected with the world, with nature, and with spirituality. There’s a New Age spirituality aspect to it that isn’t dealing with any realities. That’s my problem with it.

The issues with this movement extend to the natural world. It leans on this exoticized idea that the other cultures we’re pulling from have a better relationship with nature—but we’re not going to interrogate our relationship with nature. We’re just going to use the aesthetics of living harmoniously with nature to make ourselves feel better about things without changing any of our ways of living. We’re not going to get rid of our giant SUVs or huge McMansions or change our suburban design landscapes. Sorry—whenever I think about these things, I get cynical. (laughs)

When I first started looking into GVC back in 2017, the only way I found it was through the Seattle Central Library. They have this incredible design magazine collection that you can look through. At the time, I was hyperfixated on Y2K Futurism, and I was going through these magazines from the 90s being like, Okay, where’s the Y2K stuff? Where is it? There’s nothing here. It was all this Kokopelli-derived, global, rustic, paper stuff that dominated. It’s hard to overstate how omnipresent that stuff was at that time. And I had such a strange relationship to seeing GVC again for the first time in 20 years. I was repulsed by it. I noticed that when I showed it to other people—those were the first moments of this look being called Global Village Coffeehouse, and us finding it—they all had the same reaction: this intense revulsion to it. But they had a strange nostalgia for it at the same time. They had a pretty complicated and conflicted relationship to Global Village Coffeehouse. And now I’ve noticed over the years GVC is somewhat popular. I’m seeing people creating slideshows based on it, and they’re like, Oh, can we bring back Global Village Coffeehouse? We love it! It is strange to see.

CARI tries to highlight what was going on when this design movement emerged and the issues with this style, but that kind of gets lost when GVC gets revived in short-form content. It just becomes another design style. It becomes another purely aesthetic design style without any conversation about the context and economic and societal forces behind it. Having that get lost again is disheartening. It could lead to people wholesale reviving GVC, without thinking about the negative associations with it.

AMIRIO: You’re helping me become more attuned to how, especially in the West, through design and other proxies, we’re constantly trying to figure out how to deal with our anxiety towards the ever-present Other—whether that’s nature, people of color, other countries. It feels like there’s a constant question of, How do we deal with you?—whether through reverence that’s inappropriate, through containment, or through a complete refusal of anything that aesthetically evokes the Other.

I have one more question that somewhat relates to what you’re saying around GVC superficially gesturing towards different issues without engaging with them. I’m wondering, looking back at all the research that you’ve done and seeing how the pendulum shifts between caring about the environment and not, do you have any predictions for what a uniquely Anthropocenic aesthetic will or could look like? I feel like we’re on the precipice of our culture developing an aesthetic response to extreme pollution, more species extinction, and so on. Once it gets to the point when climate change really hits the fan, I feel like there will be really interesting responses, design-wise. Being a little bit speculative, what do you think we could see? What do you hope to see?

EVAN: Yeah, that’s a great question. Extrapolating from where I’m seeing things going is very difficult. I feel like everyone is having a really tough time visualizing the future right now. There are a lot of different design threads unraveling right now that are wildly different from each other, and it’s hard to see if any one thing will win out—as opposed to there being a continued mishmash melange of a bunch of different movements. I’m always hoping for more of a shift, as I’ve been mentioning, back to craft alongside investing more in our built environment—making it more individualized and less cold, which I have a particular problem with in Los Angeles.

I’ve been living in L.A. and noticing a lack of investment in our urban spaces that is leading to the most bland, cheap apartments going up everywhere, without any consideration for artistic expression. What I want to see in the future is, first of all, a complete move away from suburbanization—that’s just completely horrible and needs to stop. Additionally, I want to see more investment in creating fun, whimsical urban spaces and neighborhoods with people crafting little nooks, spaces, sculptures, and murals. Moving in that direction would require a pretty hard shift away from our economic system, but that’s what I’m hopeful for in the future.

We can create a sustainable urban fabric that doesn’t have to be miserable. It can be fun. We can have a better relationship with our natural environment and, at the same time, still have fun with design. We don’t have to completely abandon fun and make everything really stark and without ornamentation or playfulness. That’s where I hope for things to go because I feel like that would be the best of both worlds.

We can use the technology we’ve developed while working harder at developing a better, more harmonious relationship between our built environment and the natural landscape, and being more considerate of nature and not treating it as just a resource or something to be overcome.

The future is so hard to see right now. It feels like we’re teetering on the edge of something really horrible. (laughs) Like I mentioned before, there are positive threads and movements happening, but whether they’re able to save us in time and be implemented on a wide enough scale to avoid a complete collapse is really tough to say. We’re still so reliant on these older versions of thinking—with transporting huge cargo shipments, wasting tons of fuel, and relying too much on excessive amounts of energy, bad suburban planning, and automobile culture. Of course this all ties back to the issues with our economic system and questions around whether it can be reformed. I think a more drastic change would need to happen.

Again, design- and aesthetics-wise, I hope for a shift to a slow version of how aesthetics progress as opposed to the way they’ve been historically co-opted from subcultures or movements and then regurgitated to sell things. That is a top-down approach where corporations constantly come up with new trends and design styles that they sell to the public, and then people get bored of them. Aesthetics then get oversaturated, and it’s like, Oh, onto the next thing. That is not a healthy way for a culture or society to operate, especially not in relationship to the natural environment. A shift away from that pattern of living would be great.

Evan’s Recommended Resources

“Ep. 64: Whimsicraft w/ Evan Collins” (Evan: Podcast I recently did on Whimsicraft)

Art Deco of the 20s and 30s (Evan: Precedent book for CARI’s goals and mission)

The System of Objects (Evan: Influential theory book we use in our studies)

Learn More About Evan’s Work

👁️ More PLANTCRAFT

Amirio: Giving love to the Strange Plants Substack for providing constant inspiration when it comes to plants in design.

Amirio: Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures highlights that “[b]uildings and construction account for 38% of CO2 emissions globally—cement manufacturing alone accounts for 8%” (p. 88). Additionally, the book uplifts that “[t]he construction industry is the world’s largest consumer of resources and raw materials. 35% of construction and demolition debris is disposed of directly into landfills.” In other words, our design systems and processes, including in architecture, are overdue for a complete reimagining.

More on Zen-X, from the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute: “Popular with Gen-X and some Baby Boomers; this aesthetic emerged in the early 1990s, part of the ‘natural-organic’ shift away from 1980s excess and a resurgent wave of environmentalism (eg. Sting in the rainforest, the corporate eco-responsibility trend made famous by companies like The Body Shop, the Nature Company, etc.). This was combined with a trend towards minimalism and renewed interest in Japanese architecture and design concepts.”

More on Shed Style, from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation: “The Shed Style is easily identified by its juxtaposition of boxlike forms capped with single-sloped shed roofs facing a variety of directions. The style spread quickly through the United States after the construction of the Sea Ranch Lodge condominium complex in Sonoma County, California in 1965. [...] The use of the style in the 1970s also coincided with the energy crisis and some of the better examples employ passive-solar design elements. These features include south facing windows at the roofline (clerestory windows) paired with interior elements such as brick floors or rock walls which could collect and store heat, thus saving energy costs.”

More on Terra Centre Elementary School: “Terra Centre Elementary School opened on September 2, 1980. Our school was designed during the energy crisis of the 1970s when school facility planners eagerly sought new and creative ways of making schools more energy efficient. Terra Centre was the product of a unique design concept - a school built largely underground. The roof of Terra Centre was covered with earth, 3 feet deep, to mitigate heat gain in the summer and heat loss in the winter. The architect designed windows and skylights to let in plenty of natural light so the school would not have a dark and gloomy feel as parents initially feared. A bank of solar collectors was installed on the earth covered roof in 1982.”

More on Frutiger Aero, from the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute: “Greenwashed tech aesthetic of the 2000s-2010s. Features tertiary color palettes, stock photos of nature, glassy 3D orbs, bokeh blurs, & auroras. Glossy skeuomorphic GUIs & humanist sans serif type were popular trends (especially in the respective Aqua and Aero design guidelines for OSX and Windows). Soothing, sine-wave based ambient menu music & UI sound design. Personalized product design colorways, especially in tech peripherals like first wave smartphones & MP3 players (via the Four Colors motif). Green architecture & transportation like living rooftops, solar panels, and first wave hybrid EVs. Interior design using white plastic, glass, & bamboo materials. Documentary films & social campaigns on global warming, healthy diets, and agriculture. Common themes of harmony with nature, humanism, & climate consciousness--driven by brands with the intent of appearing eco-friendly in marketing, despite never changing their actual actions.”

More on Memphis-Milano, from the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute: “Designs of Memphis Group, Studio Alchimia, and those inspired by their geometric, colorful designs across the world in the 1980s.”

More on the Y2K Aesthetic, from the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute: “A time when the future was tight leather pants, silver eyeshadow, shiny clothing, oakleys, gradients, and blobby electronics.”

Amirio: I want to share a few reminders about plastic production from Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures. Firstly, “[m]anufacturing fossil-fuel-based plastics generates 3.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and rising. From 1950 to 2022, annual plastic production grew from 2 million tons to 400 million tons, and is projected to triple to 1.2 billion tons by 2060” (p. 88). Additionally, “[g]lobally, only 7.2% of all materials are reused, and only 9% of plastic waste is truly recycled—actually turned into new things.”

More on Vectorbloom, from the Evan Collins: “That early 2000s-very early 2010s aesthetic fascination with vector-graphic tools, photo collages + digital effects applied to create explorations & manipulations of natural forms, sometimes harkening back to 1960’s psychedelic and the earlier Art Nouveau style. This one was huge in the 2000s in general, was noted by TVTropes as ‘Design Student's Orgasm’, and was catalogued rigorously on the design blogs of the era, which I imagine are almost all gone by now. Has ties to the McBling & Modern Baroque aesthetics.”

Amirio: I want to shout out other platforms doing rigorous, brilliant work in the aesthetics research space, including Nymphet Alumni and Silent Generation.

More on Eco-Shed, from Evan Collins: “Architectural & interior style + consumer ephemera associated with the first wave of environmentalism in the late 1960s-1970s, some hippie culture influence. Macrame, wood cladding & paneling, heavy use of plants, and the 'Shed' style of architecture pioneered at Sea Ranch, CA in the 1960s.”

More on Eco-Beige, from the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute: “Stripped-down, eco-oriented early 1990s aesthetic. There's something about this style, where it seems like an attempt to distance itself from 1980s excess, and seem more stripped down, unpretentious, eco-friendly, and down to earth. Beige, soft natural tones, twigs, raffia straw, linens, wood, exposed surfaces, textured walls. Not usually super-detailed or ornate, using simple handcrafted forms or just natural forms.”