When you are all of the same thing, then you have to go to the fine point. In other words, if I’m a Black queen and you’re a Black queen, we can’t call each other “Black queens” because we’re both Black queens. That’s not a read—that’s just a fact. So then we talk about your ridiculous shape, your saggy face, your tacky clothes. Then reading became a developed form, where it became shade. Shade is, I don’t tell you you’re ugly, but I don’t have to tell you, because you know you’re ugly. And that’s shade.1

Four notes on throwing shade:

i.

Knowing me means knowing my love for Luther Vandross and all his constituent parts: his faultless, impossible voice; his ascendant vocal arrangements; his diva worship; his mastery of translating pure feeling into billowing, verdant groove-scapes; his stewardship of camp and glamour; his ambition; his assertion of Blackness into the DNA of everything he touched; his beauty; his queerness, in multiple registers; his husbandry of other talents—vocalists, songwriters, musicians—both seasoned and new.

And his puncturing shade.

In the Dawn Porter-directed documentary Luther: Never Too Much, archival photographs and videos, celebrity cameos, and reverence-thick storytelling from those within Luther’s innermost circle are stitched together, forging an impression of who Luther was: a Black musical genius besieged by the same violences that so many Black musical geniuses had faced before him and continue to face in the wake of his life. As far as giftedness, Luther was singular, a Martian—as or more talented than his peers and perhaps even his predecessors. Though lauded by the entertainment world for his inherent too-much-ness—too much sonic precision, too much incontrovertible vocal skill—he was often marooned to the margins by an entertainment industry that deemed many of Luther’s other abundances as unworthy: too much dark skin, too much fat, too much butch queenhood that disturbed the borders of acceptable Black man-ness. What tools of redress are afforded those whose personhood is a state of emergency for the status quo? For Luther, one was throwing shade.

Within the pantheon of shade sits Luther, shoulder to shoulder with Patti and Aretha and Prince. Across the artifacts of their lives, throwing shade is present as a means of armoring against a music business that dispenses the same brutalities as the wider world. In Never Too Much, we see Luther activate shade—an innovation of survivors and not-survivors of anti-Blackness, white supremacy, femmephobia, transphobia, misogyny, homelessness, economic inequities, disease—to shield himself. In deft interview quips, in witty comebacks to probing journalists, Luther, often volleying between acrimony and humor, throws shade to enact refusal: refusal of scrutiny around his weight, refusal of inquiries about the gender of his intimate partners, refusal of the denied plausibility of his crossover appeal. In one moment in the film, his exaggerated boredom with an interviewer’s gossip-hounding questioning has a defensive edge. Luther’s linguistic play, often reserved for architecting songs-cum-cathedrals-to-tenderness, becomes a blunt object.

Something almost spatial, architectural, and ecological happens when Black folks throw shade: a canopy of sorts emerges, under which one can preserve and cultivate their self-regard and standing through levity and sometimes venom. In the shade, I wonder if Luther found some relief, however temporary and inadequate and unable to prevent a death that continues to feel premature.

ii.

Throwing shade as dignifying. Throwing shade as social etiquette. Throwing shade as sociality. Throwing shade as memorialization and ancestral reverence. Throwing shade as Olympic sport. Throwing shade as communal criticism and intraclass antagonism. Throwing shade as showing these bitches what time it is. Throwing shade as the swamp. Throwing shade as the cave. Throwing shade as the shipping crate. Throwing shade as the oyster house. Throwing shade as the tree cavity. Throwing shade as the church basement. Throwing shade as the porch. Throwing shade as the juke joint. Throwing shade as the quilt. Throwing shade as the beaded plait.

iii.

An excerpt from an essay I wrote for the Museum Ludwig in 2022 entitled “‘Polymorphous Perversity’ as Portal: On Lili Elbe, Plant Sex, and New Worlds.” The full piece is about Lili Elbe, who became “the historical record’s first person to undergo a sequence of gender-affirming surgeries.”

The portrait of Elbe, a Danish trans woman assigned male at birth, and Lejeune calls to mind another image: a GIF of American multi-hyphenate artist Juliana Huxtable, who was born intersex and also determined to be male at birth (in 1987). The GIF’s looping frames preserve Huxtable’s response to an unseen interviewer asking, “What’s the nastiest shade you’ve ever thrown?” Her answer is curt but cutting: “Existing in the world.” Huxtable, an embodied disordering of a bifurcated gender system, raises up how living out gender opacity and living into a world where gender is boundless (or even an aside) is a dangerous affront—an eye roll, a sizing up, some nasty shade—to the dominant gender expectations of the West.

[…]

More venomous than Huxtable and Elbe combined, plants throw the nastiest shade of all. Before Elbe would mark a milestone in fracturing the foundation of an intrinsically fallacious and deleterious two-gender structure, fledgling explorations of plant life would reveal human approaches to living as inadequate, unimaginative, and violent—and would also play a hand in creating the loam from which Elbe would emerge.

iv.

“Shade undresses / the duress”2

In the shade, overheated bodies return to equilibrium. Blood circulation improves. People think clearly. They see better. In a physiological sense, they are themselves again. For people vulnerable to heat stress and exhaustion — outdoor workers, the elderly, the homeless — that can be the difference between life and death. Shade is thus an index of inequality, a requirement for public health, and a mandate for urban planners and designers.3

Moving away from considering plants as discrete entities to considering plants as assemblages of interacting parts, this PLANTCRAFT missive, for the first time, is anchored in a critical component of botanical life: shade.

“Shade” is a prolific word fecund with meaning. I look to one of my notebooks, where I’ve attempted to diagram some of the ways our senses register shade: as an object, a gesture, an ecological phenomenon. In this broadcast, I’m interested in all the textures of shade, especially shade as a site where life and death are mediated.

While commonly understood as relating to a scarcity of light, shade, in one understanding, is a sophisticated environmental formation that informs the flux of life in our ecosystems. In journalist Sam Bloch’s foundational article “Shade,” he argues that in the places humans inhabit, shade—made possible by vigorous tree canopies, by sun-effacing architecture—must be re-understood as a “civic resource that is shared by all” instead of an unequally distributed “luxury amenity” that prescribes relief for some and risk for others. In this month’s missive, I survey the full spectrum of shade with guest MaKshya Tolbert.

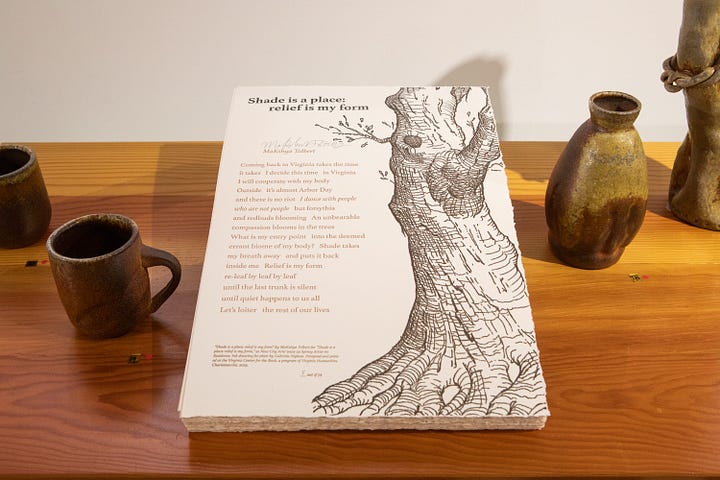

MaKshya (any/all pronouns) is a poet, wood-firing potter, land steward, and researcher who recently made her way back to Virginia, where her grandmother raised her. She is the 2024 New City Arts Guest Curator, a Fralin Museum of Art 2024 Writer’s Eye Fellow, a 2024-2026 Fireline Fellow (Patricia Valian Reser Center for the Creative Arts), and serves as Chair of the Charlottesville Tree Commission. Her debut collection, Shade is a place (Penguin Books) will be released in October 2025. In her free time, MaKshya is elsewhere, where Eddie S. Glaude, Jr., calls, “that physical or metaphorical place that affords the space to breathe.”

In the first broadcast of the new year, MaKshya and I discuss MaKshya’s role as chair of a city tree commission, loneliness as a life-giving force, the continued resonance of the film Space is the Place, and shade as an embodiment of what’s possible for Black life within the global miasma of anti-Blackness. Will you play in the shade with us? (This conversation took place in November 2024 and has been edited for length and clarity.)

AMIRIO: When looking through your work, I loved seeing how your bio online and the way you've chosen to describe yourself and the work that you do has shifted over time.

In one bio, you called yourself a “shade walker.” I love that role, or title, that you gifted yourself, especially because it feels like you’re making shade something we can have an intimacy and relationality with. There’s a kind of warmth and poetry that you’re ascribing shade that I thought was really lovely. For you, what is a shade walker? How did you come to call yourself one?

Also, more broadly, I love how you describe your curiosity with shade as being a practice of being in awe. How did that come to be? How did you become interested in shade? I’ve followed your work for a minute, and I know you’ve worked across so many disciplines, practices, and materials: I’ve seen you juggle, you write poetry, you work in ceramics and pottery. Throughout all the work you’ve done, how did shade become this core curiosity, and how has that curiosity evolved to you being a shade walker?

MAKSHYA: I don’t drive, and walking has been the pace of my movements. For the most part, walking is the way I get to be autonomous, the way that I get to transport myself.

I found myself moving back to Virginia three and a half years ago and using walking to orient myself to where I was and to start asking myself these questions about relationship; it’s a way of asking, How many laps will I walk the Downtown Mall before I find someone to talk to, or before I feel like there’s something here for me? So, I returned to Virginia and started walking and noticing what’s around. And at some point within this practice begins this curiosity about all of these stressed-out shade trees. So, before I got into shade, I was thinking about walking. I was walking this one pedestrian mall, the Downtown Mall in Charlottesville, Virginia, that’s around eight blocks, and I was trying to get a sense of who was there, what is Charlottesville, who I am. And I started reading how other people taking walks—long walks—were writing about their lives. I found myself reading these walkers.

I am going to name some people who sound crazy: Meriwether Lewis and John Muir and Charles Darwin and Frederick Law Olmsted and Bashō. I found myself curious about the footsteps and walks of these men who had time. And I found myself wanting the time that they had. And a lot of the questions that were coming up for me reminded me of some of their questions. I was curiously seeking what’s possible in the midst of the entanglements between property and slavery and money and anti-Blackness. The history of certain walks then became something I had to face. The forced walks communities were made to take as the U.S. government started to imagine itself as a place. The story of York, an enslaved Black man who participated in Lewis and Clark’s travels. Olmsted’s walk across the South, which was mostly him walking and observing Black life. I wanted to entangle myself in movement and in something that was embodied but also historical. There’s something about walking as being both recreation and work that was also on my heart.

With my work on shade, I wanted a form that was embodied and to find a way into a creative work that required me to move. That’s what I’m thinking about on my personal walks. That’s what I’m thinking about when I’m leading my guided walks. And that’s what I’m thinking about on the page when I’m trying to figure out a kind of creative and poetic form for these walks.

AMIRIO: I’m interested in this idea of walking being a way of enacting a form of recreation and labor. That feels especially true when thinking about Black people who are adopting the stance of a flâneur: when moving through any kind of space, especially public space, there’s always this labor that’s attached to it, particularly for Black folks, because our bodies are always moving between these poles of care and precarity. I’m wondering what kind of labor you have to enact and what you have to attend to when walking around in a place like Charlottesville.

In the broader cultural imaginary, when we think of Charlottesville, we’re thinking of racial reckoning. We’re thinking of Trump. We’re thinking of white supremacy and racial terrorism. So much imagery attached to Charlottesville brings up all of that. Again, what kind of labor do you do while walking? You must have to attend to so many historical narratives, alongside your bodily autonomy and safety. There must also be the labor of wanting to be in leisure and attend to the ecology and attend to yourself and the fact that you’re trying to be place-full within a period of placelessness as you transition back to life in Virginia.

MAKSHYA: I love this idea that you and I are working on together: that there’s walking and then there’s the continuum of inner life with which one walks. There’s the labor of walking, and there’s also the leisure of walking. And Shade is a place, my book project and social practice, is about all of those things.

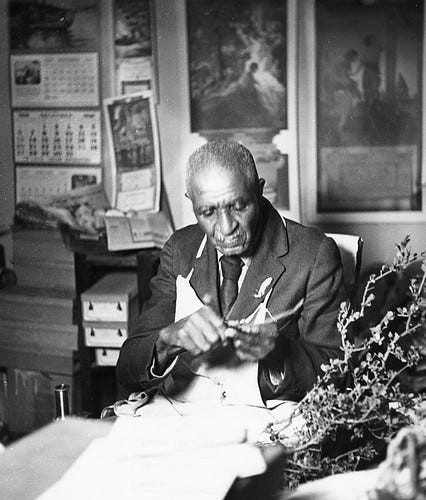

When I think about the leisure of walking, I think about George Washington Carver and the mysticism of his life and what he called, on the walks he took every day, his “little talks with God.” And he talked about the earth being God’s broadcasting station.4 That’s so funny to me, to think about Carver tuning in every day to God and to the earth. Is there a pace of my walks and of my shade walking that longs for that? To me, the awe is both in the leisure of walking and the labor of walking. The Black walkers that I feel like I’m apprenticing to are pushing me into the leisure and pushing me to not just limit what a walk can be—as beyond something so duress-filled. That said, the entanglement and flux captured by walking is what it means to live—in that movement between leisure and labor.

My walks are my attempt at acknowledging the sense of separation that comes with moving to a place where you don’t have a sense of belonging and becoming lonely. I didn’t witness the events that people talk about when Charlottesville comes up, including slavery. (laughs) I wasn’t here to witness the Unite the Right rally in August 2017.5 So, in many ways, the labor of walking includes walking through the traces of those moments and walking through a place that wears its history—in the built environment, in the arbor, in the canopy ecology. I’m in a place that holds the remnants of all its social and economic lives.

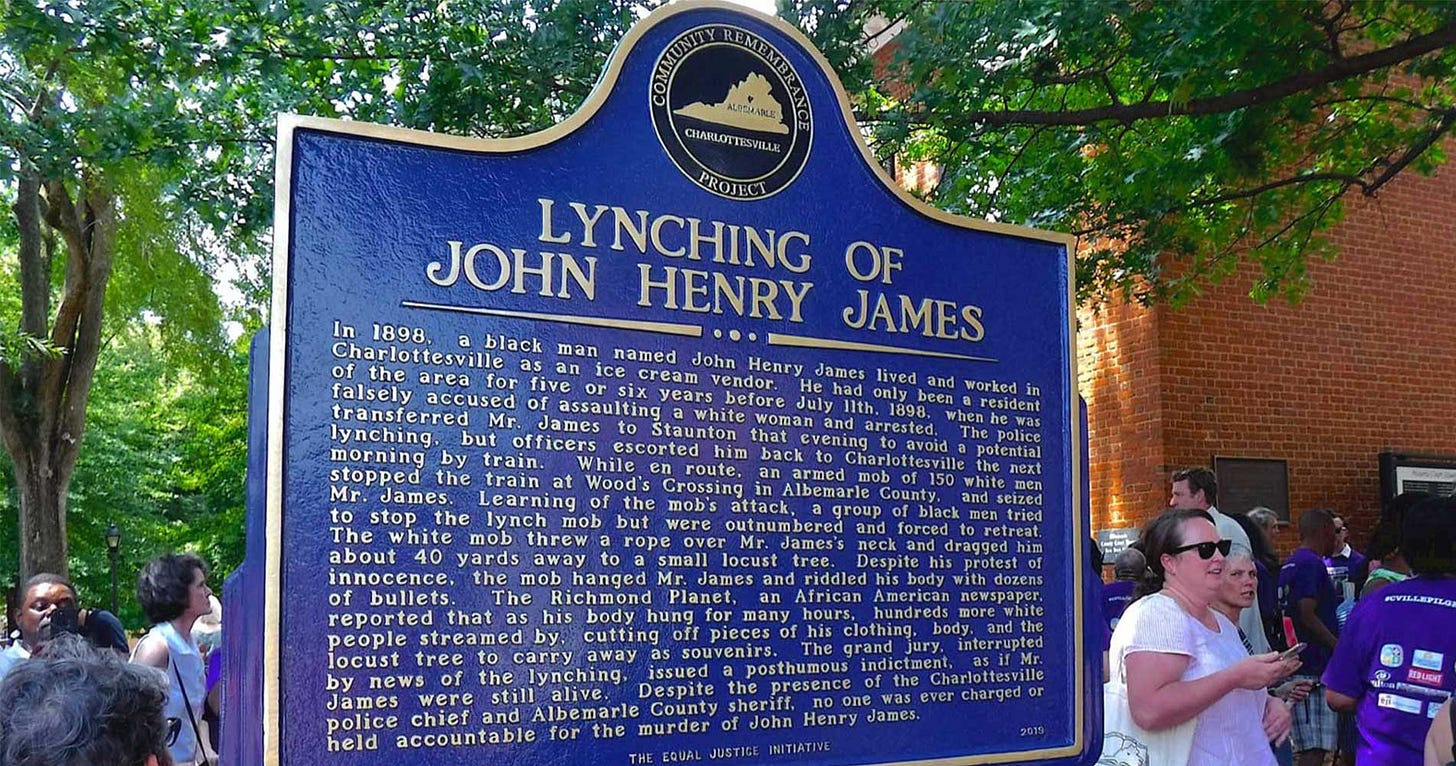

I’ve been thinking a lot about the sites where racial terror and lynching occurred and asking myself, What does it mean that we know a Black man, John Henry James, was lynched on July 12 in 1898 near Charlottesville? The place near where James was murdered is now home to a privatized golf course at the Farmington Country Club, but the plaque that commemorates his life is in downtown Charlottesville.6 So, I end up walking every day past the plaque that commemorates John Henry James’s life, even though the actual route of his death is somewhere else. The labor of walking includes trying to get from one end of the Downtown Mall to the other at the pace of what’s happened already and at the pace of what Christina Sharpe might call the “atmospheric conditions of time and place.”7 In Charlottesville, in the Downtown Mall, you walk through the weather, both the atmosphere and social life: you walk through the redlined boundaries and you walk through the agreements to revitalize the Downtown area and you walk through places that hold traces of Black life.

So, I wonder if shade walking can be a way to account for the whole spectrum of walking when underneath trees—through the duress, carrying my own histories and sometimes those of others. How can we walk through the curiosity, possibility, and vigor of the canopy? How can we consider shade walking as a way of living in that entanglement? And maybe Shade is a place is acknowledging the breadth of what it is to be a person. Maybe that’s why there’s something about Meriwether Lewis’s walks, and this is so inappropriate, but I think about a person like Meriwether and a person like Harriet Tubman, and I think about what it’s been like for myself to link them in a troubling yet curious sense and see a kind of ecological attention and curiosity and entanglement in both of their lives.

Overall, I think labor and leisure are really apt and dynamic ways to think about some of the poles that exist when you go outside and walk the same route—in the repetition of same place, same trees, same architectures.

AMIRIO: I love how you’re thinking about shade as being about, using your language, “the breadth of what it is to be a person.” And I love the complexity, the sort of and-ness of those two poles—labor and leisure—and how they have to hold hands.

I want to talk about Shade is a place a little bit more—as an idea, as an umbrella term for what you’re studying, as the title of your debut poetry collection coming out next year. When seeing the words “shade is a place” for the first time, I immediately thought of Space Is the Place—the 1974 Sun Ra film where he’s this iconically self-styled, spacefaring prophet who’s spreading the word about the outer reaches of space, the expanses of the universe, as being a safe harbor for Black people on Earth. The outer reaches of space are touted as a place of leisure and refuge. Shade is a place and Space Is the Place are thinking about similar ideas: leisure, refuge, belonging, moving beyond a feeling of placelessness. Can you further clarify how you’re conceptualizing shade, alongside and beyond ideas of shade as something we associate with trees, with Shade is a place?

MAKSHYA: To be in a conversation where Sun Ra’s work and practice are coming up is an honor to me.

Shade is a place emerges out of a real and material need for relief—somehow both always including myself and also relief expressly beyond my own. I would say “not necessarily even my own,” which reminds me of Tiya Miles’s Night Flyer, which attends to Harriet Tubman’s movements and ecotheology. I keep returning to the way Miles reflects on Harriet Tubman’s willingness to push her body; what does she quote Tubman saying? “When the time came for me to go, the Lord would let them take me.”

Anyway, when I began this project, the first “nugget”, if you will, was being reintroduced to the Jena 6 and reintroduced to these six young Black children—these teenagers who I had heard about as a kid. Recounting the Jena 6 events: what starts as a young Black teenager’s request to sit under a shade tree that white children at Jena High School sit under becomes the site of so much duress and violence.8 One day, this Black child asked, “Can I sit under this tree?” And their principal said, “You can sit there, but what happens to you is not my business or my problem.” The next day, there were nooses under the tree.

The white teenagers responsible weren’t punished sufficiently. What ends up happening is that the Black and white students start fighting and, ultimately, five Black boys are charged with attempted murder. The school gets damaged by arson and the tree gets cut down. I distilled some of what happened with the Jena 6 down to being about the consequences of seeking shade and the consequences of seeking relief. I found myself wanting to know what are the properties of shade such that we would be in that level of competition and lovelessness over the desire for relief. So, I say all of that because the way that I’m thinking about shade as a place, as a possibility of gathering, is in the wake of the Jena 6—and in the wake of a plantation economy that relied on clear-cutting forests so that you could build a world. I was also considering my own stressors, as I watched myself try to go out on the Mall, basically running on empty and trying to use that exhaust to forge some capacity for relief, for myself and others.

I entered shade with this desire to see if there was something otherwise that could be possible—something that is alternative to the duress and to the stress. And I entered shade to envision an Elsewhere. When I think about Elsewhere, as you’ve seen in my bios, I’ve been teleporting myself to where Eddie S. Glaude, Jr., calls in his writing on Baldwin “that physical or metaphorical place that affords the space to breathe.”9 And something about that idea means there’s an Elsewhere in my body that is already capable of breath. I began to feel the Elsewhere of my own body, or of the shade trees, or of the Mall—noticing that you can actually move that place, that Elsewhere, to either be hidden in plain sight or to be otherworldly.

So, I think about Space is the Place and Shade is a place as both rehearsing this Elsewhere, or this possibility of being. Where is there Living Room? And when I say “living room,” I mean in the way that June Jordan was writing about needing more Living Room10—more breathing room. There’s something that’s not so much about forcing a geography—Is it here or is it here? But it’s something about the commitment to attention and relationship that is what space might be, what Shade is a place might be.

AMIRIO: I want to think about the practice of “throwing shade,” which I would classify as one of my favorite ways Black and queer people refuse: refuse bullshit, refuse misinformation, refuse draining energy. Throwing shade has a protective, armor-like quality, which aligns with how you’re thinking about shade more broadly. When holistically thinking about your interest in shade, what or who are you throwing shade at? Who or what are you trying to go against, antagonize, trouble, acknowledge?

MAKSHYA: I love this question! It’s, again, one of the gifts of being in conversation with another person who’s just so moved by Black ecological attention.

The question you’re asking is actually one about one of my first real anxieties about this project, which had to do with not understanding if the project was about language and abstracting shade into being about these other lives of the word, or if the project was about a desire to write something that was accountable to the material world and to the stresses and needs of trees and of people. I spent the first year of this book project trying to force myself to resolve that ambivalence before I understood how entanglement works. But I say all that because initially I was so protective of throwing shade as a kind of Black articulation of relationship, distance, and frustration that I didn’t want to use it. I didn’t want to use the phrase, and I also didn’t want to enact throwing shade, partially because I think I was afraid, at first, of being myself. And afraid of sounding how I sound, and afraid of the resentment, and afraid of the cleverness, and afraid of seeming too strategic or manipulative with words—even though that is so much of what a poet wakes up to do.

My initial refuge—my initial false refuge—was in the fact that “throwing shade” is also a term that our urban forester uses to describe getting as much shade—like trees on the ground—as fast as possible. I would hear this man say, “I want to throw as much shade on the ground and as fast as possible.” (laughs) But he would mean it in the most literal way. I hid behind that use of the phrase until I felt ready to play. In the book, you can see this project where I’m working so hard, as quickly as possible, to acclimate to the work that’s happening—the literal work happening. However, over the last few years, watching myself embody the work and start to lead shade walks on the Mall and start to really build a social life in Charlottesville—my personality came back into the work.

I’ve been thinking about throwing shade as something that can be quiet and not spoken. When I would walk around in the Mall, just minding my business and messing around and being so at ease, it felt like a form of shade—the act of defying expectations of what I should sound like or talk like. The other thing on my mind about throwing shade is about W. E. B. Du Bois, who wrote about the 1916 Amenia Conference.11

Du Bois is writing about this Black gathering on the property of a really famous white, Jewish naturalist, Joel Elias Spingarn. They’re in upstate New York, and Du Bois is writing about the three days they spent there, and he says, “I had no sooner seen the place than I knew it was mine.” When reading that for the first time, I go, Wait—did he just describe a weekend at this property as basically belonging to him? (laughs) I thought it was so funny to hear him talking about this conference, that’s meant to be about processing “The Problem,” which was how they were describing talking about white supremacy, and to hear him talking about him and the other participants—these Black folks—singing in the hills and frolicking and rowing and hiking and being like, We had a blast, actually.12

But, overall, the thought of incorporating throwing shade in my work scared me. It scared me to let my desire for that come through, and it took me a while to be willing to wear it. And it took me having to take a step back and focus on the stresses, in a way. At first, there was just no room for play, there was no room for refusal. All I wanted to do at first was know where I was. And then I started to get a bit more open. Just one more time: Du Bois literally says, “We ate hilariously in the open air.” That’s him writing about this very serious conference. “[W]e broke up and played good and hard. We swam and rowed and hiked and lingered in the forests and sat upon the hillsides and picked flowers and sang.”

Throwing shade is like shade walking in that it can live on this spectrum, from being a way to survive to being a way to play. And also a way to ask a question. I love this possibility of finding everything to be so wide. Now everything’s a continuum to me. Even my pronouns have been changing so much. What started as a desire to be seen one way opened up. My curiosity was moving, and the way that I needed to be called into a room was changing. Everything is in flux, and the flux is the condition—and maybe the adaptation.

AMIRIO: We could linger so much on abstraction, getting at what you said earlier, but there is also a very material element of shade. The place I want to land on is your role as chair of the Charlottesville Tree Commission. I want to talk about that for a minute because that’s such a specific role that feels so outside of what I’d expect an artist to do and be involved with. I love how your curiosities have gotten embodied and lived-in to the point where you’re in this role. How did you come to that role? What does it mean to be on a tree commission? How does your work as chair relate to Shade is a place, this overarching, ever-evolving body of work?

MAKSHYA: Yeah, this is going to be fun! So, you and I are both really drawn to this question: What do I make of shade? All of its different abstractions and articulations—haints, Dante’s shades, what it means to “shade” as a verb. What is the gestural or movement-based work of shading something? Three years ago, I reintroduced myself to the Jena 6, to these young Black people, and I’m thinking, Shade is hurting me. What happened? And I heard myself asking, What are shade’s properties? Why is shade so propertied? What is this? What do I make of something that means so many different things, not to mention a condition of low light or comparative darkness? I had no idea where to start with shade.

At the same time, I was in this city, Charlottesville, that I was new to and had so little intimacy with, and our Black mayor, Mayor Nikuyah Walker, wasn’t seeking reelection—and our Black police chief, RaShall Brackney, had just been fired as Chief of Police for the City of Charlottesville. I entered this place where, at least to me, Black women’s jobs were breaking down. Maybe hearts, too. At some point, someone suggested that I stop going to city council meetings and go to a Tree Commission meeting. Little did they know that I was just reading about shade. So, I was like, You know what? Maybe I should go to a Tree Commission meeting. And someone said, Yeah, at least they like each other. I wanted to go see about that. I was like, What do you mean there’s regard and shade? I would love to be a part of that. I would go sit in on the meetings and eventually the Commission members asked me who I was and why I was coming to meetings that so few people in town go to. When I shared that I was just curious about shade and didn’t know where to take myself, they offered, Why don’t you join us? We could really use the diversity. (laughs) And I said, And I could really use your meetings.

There was something mutual, in some ways, in a trickster way, about being like, You said you want something. You said you want something, too. You get to have a Black person in the room, and I get to build my intimacy with shade trees, and we’ll just see who gets what. To be fair, three years later, I’m chairing the Commission, struggling through these entanglements of race and representation and regard and dignity, on a team of people who are charged with advising the City of Charlottesville on tree planting and preservation on public properties. And if there’s time, and you’re not too scandalous, maybe you can talk about what the City might consider on private properties.

Initially, I would just show up and, two hours a month, I’d try to offer voluntary capacity to projects. The first project I was a part of was the only one within walking distance. There were going to be five trees cut from the Downtown Mall; they were dying and had all of this rotting and dieback. And I figured, Why don’t I apprentice myself to the place that’s five blocks from my house and take part in this transition? At the time, there were 73 willow oaks on the Downtown Mall and they were going to cut five. I thought, Why don’t I just go watch and be a witness and watch these trees transition and watch this place change? If there’s anything to write about shade, I have to imagine that something will come through this experience. So, again, I would just go to the Commission meetings and show up and be in the way or a fly on the wall, depending on my mood.

Before I knew it, I was so moved by the architectural history of the Downtown Mall, because that’s part of where the Commission’s work is. When you’re felling trees on a pedestrian mall with businesses and families and children and all of this life, there’s a large amount of care that has to come through. I found myself watching these white men being so caring and so attentive—and I’m feeling weird. I would notice these feelings coming up in the work: Why is this work so intimate? Why is there so much curiosity and awe in me? What are these feelings? How do I focus on the trees when I’m also thinking about all of this other stuff? All of that started to build a site to focus on and a place to be a part of. And all of that became the anchor for the book because Shade is a place is set on the Downtown Mall. Each of the book’s four sections tries to build a sense of place, little by little, one walk at a time, one poem at a time, with these trees that are slowly getting cut, or thinning, or both.

AMIRIO: I’m stuck on this piece of how the Commission members wanted something from you, in terms of race and representation, and you negotiated the terms of your involvement by coming with this trickster energy and asking for access to this governmental, administrative body for your own research. And it’s interesting how, over time, your participation has grown into something that seems very meaningful for you.

I want to stay with the Tree Commission more. You mentioned tree cuttings, and I’m curious about the day-to-day of a tree commission. Specifically, when it comes to canopies and shade in Charlottesville, what’s happening on that front currently that’s interesting and activating for you?

MAKSHYA: All of it is activating, I’ll tell you that. I have to admit, the administration of the arbor is politics.

AMIRIO: What does that mean—“the administration of the arbor?” Why is that political? In that, where is there political life, and why should we be concerned about it, or at least paying attention to it?

MAKSHYA: It took me six months to learn this, but every single tree in Charlottesville is owned and is under the property of an entity. A fifth of the trees in Charlottesville are on public property, which is to say that those trees are City property. The decision-making, the maintenance, the watering, the planting, the felling—all of that is the City’s work. It is that 20% of trees that the City is responsible for, and the Tree Commission is invited to provide guidance. Whether or not the City does anything that the Tree Commission says is a completely separate conversation. But, we’re invited as appointed volunteers and commissioners to provide input on that 20% of trees.

All of the other trees in town, besides those on these sort of creative, errant spaces owned neither by property owners nor the City, are owned by private property owners: residential properties, apartment buildings with property managers and leasing companies. They own those trees. And then you have businesses and parking lots and other projects where trees are under a kind of contract. So, I say all of that because when you understand that trees are seen as property, and you’re in Virginia, you’re invited into what it means to think about how a city or a family manages property. Who pays for the work? Who pays for the upkeep? On my end, as a Black femme studying ecologies, the afterlives of property are so intimate for me. I’m always thinking about people and trees and the earth being seen as something fungible, something renewable, something that merits being manipulated over and over again for whatever is wanted. I don’t play when it comes to thinking about the entanglements that come with these trees being seen as property.

A lot of the Tree Commission’s work is about trying to get the City to be as responsible as possible within their legal rights and pushing them to be creative when it comes to what is legal when it comes to managing trees—when it comes to stormwater management, adjusting and adapting to a changing climate and to heat, rectifying the disinvestment and razing of so many Black neighborhoods, addressing the removal of homes and trees in communities on the margins so that the City can have more parking lots or more white corridors for recreation and leisure. Lucille Clifton said, “being property once myself / i have a feeling for it, / that’s why i can talk / about environment.”13 Those are the first few lines of a poem of hers. I think about my work with the Commission and my life as being my way of playing around with the entanglements Clifton is naming.

So, again, a lot of what I do is try to push the City of Charlottesville in collaboration with this group of commissioners—most of whom look and act and talk nothing like me but share a capacity to respond to the work. And we’re doing all kinds of things. For example, we’re trying to get the City to restructure its stormwater fee, which it collects as a utility. The Tree Commission has its projects, but you’re so limited by cities, which are often not known as creative, collaborative places. There have been all of these things that I’ve longed for, all of this care work with the Commission—what I’ve been calling “mutual shade.” Mutual shade is how I feel about the Commission: other commissioners might have said, Well, we want you for this specific reason, not what you said. And I was like, Well, I want you for this specific reason, not what you said—and there’s something there for us all. It’s actually quite tender. They surprise me. Jeff Aten, if you’re reading this, thank you for your curiosity.

I saw that the Commission wasn’t in the best position to conduct racial equity work. Or wasn’t in the position I expected. I don’t know. There’s nothing there that sets us up to operationalize or formalize networks of care. I had to come to terms with that being neither our work nor our gift. Equity as a driving force would be something that I get to do and practice on my own with my relationships, with my collaborators. And that’s why it means so much to me on my shade walks to ask, How can we support each other’s energy burdens? How can the work of my walks quite literally provide either money or funding or resources to offload folks’ air conditioning bills or heat bills? And what is the relationship between shade trees and cutting down trees from public sites? And as we lose shade, are there other ways that we can put it back—put the relief back? Can we relieve that burden here or elsewhere?

AMIRIO: You really struck me talking about trees as property, especially as two descendants of people who were seen as property. (Or maybe as two people who are seen as property). There’s something there that’s really striking. Thinking about Black people and our arboreal lives, what does it mean for property to create relationality with property—and what does it mean for property to advocate for property? There’s something there that I really want to land on and stick with.

Firstly, I’m thinking about Black people and our relationship with arboreal kin. There’s so much there that is challenging: when we think of Black people and trees, we already know the imagery that often and immediately comes up. I’m wondering for you, whether in your own life or the lives of other people, what are those moments of Black arboreal life that feel like a portal to thinking otherwise about how Black people relate to our tree relations, outside of the usual histories and narratives that so often come up?

Additionally, I’m thinking about how we transform how we see trees beyond the idea of property. What has to change for us culturally, imaginatively, socially, and so on to make that happen? For far too many of us, we know trees are important in some way in our day-to-day lives, but trees are still often seen as property, as background. So, I essentially have two questions in one; take them however you want.

MAKSHYA: I’m so happy that we’re talking! What you’re saying—you phrased it, in one sense, as “property relating to property,” depending on who you ask—is making me think about two things: self-emancipators on the Underground Railroad and visual work—which are related to two projects that I’m currently working on. One is a design project, and the other is a second book.

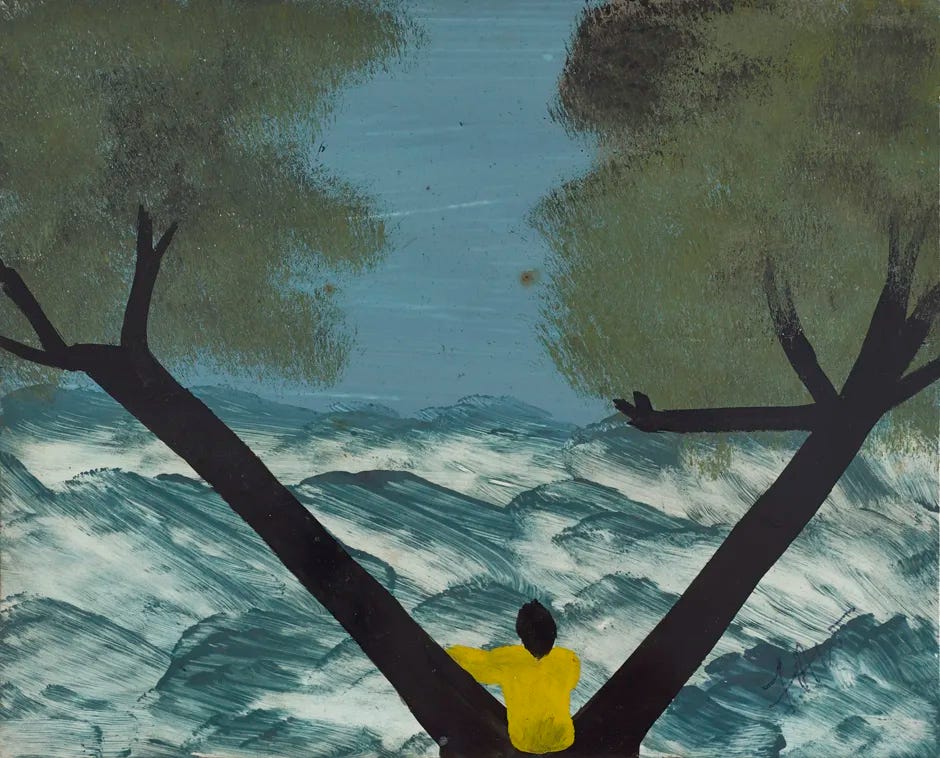

The second book is me taking a different pace and thinking not so much about a “Black sense of place,” to quote Katherine McKittrick, but a Black sense of pace. I’m wondering about how slow I should go or what position I should be in when I try to be in my life. And I’ve been writing a lot about shade trees and visual work and thinking about what it’s like for my attention to trees to also support my attention to making. And I also have this project where I’ve been writing this notebook in conversation with the work of an artist in Charlottesville named Autumn Jefferson. I recently saw the art that I want to show you real quick and it just teleported me. (shows artwork) I felt like I was both in my inner life and in the woods and on the Mall and in all these relationships all at the same time. I was just so moved by the flux.

The piece is called Growth Tensions. And I find that when I’m sitting here, looking at the piece, I start thinking about the woods as I know it, about our city as a woods or as a forest and as a set of living and built relationships.

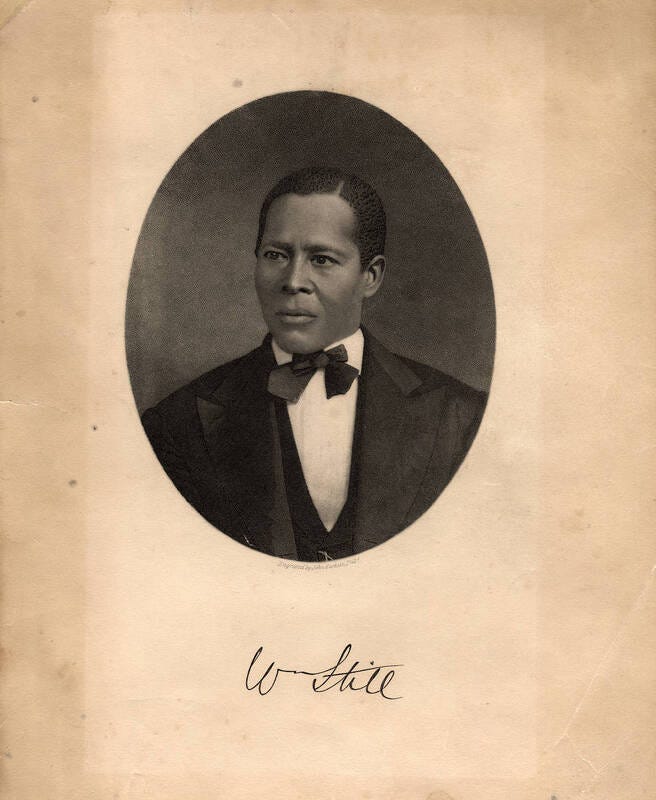

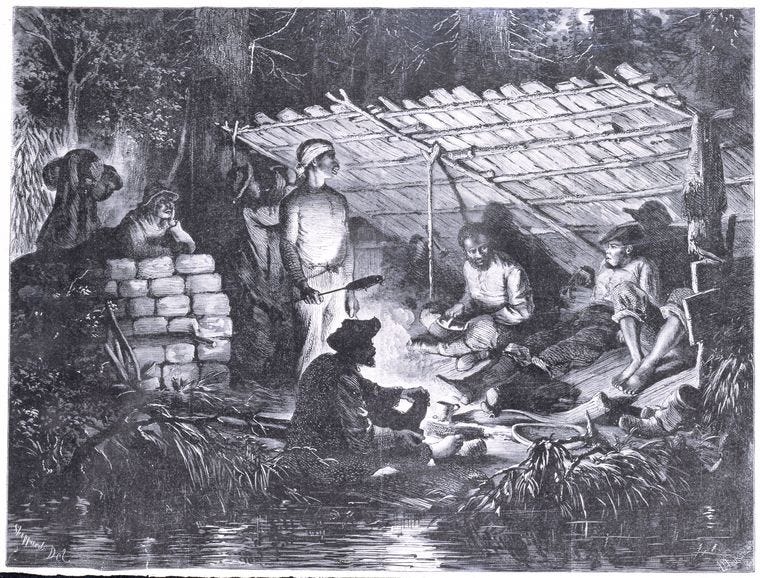

And then I’m thinking about self-emancipators in this other thread. In particular, I’m so moved by this relationship that some folks had with the forest, where, on one hand, you have a temporary refuge from what you left, and, on the other hand, you need that refuge to support your movements elsewhere. I’m trying to understand the brilliance of Black folks reading their landscapes. There really were folks looking at the stars and reading them.14 What else were they reading? And I’ve been opened up to many archives, including William Still’s archives15: he had almost a thousand Black people coming through his house, and he was secretly keeping this journal about their movements and burying it at night, not at his home. I’m also thinking about folks who were using moss to read North by noting the wetter moss on the north side of a tree trunk (John Brown’s narrative, the Black one)16—and the folks who were living in tree cavities and experimenting with what you can do in a tree. Folks who were building this sense of place and, in some ways, moving through places that were extensions of the ecologies they came from. A lot of folks who made their way Elsewhere on their own terms were leaving the Upper South—the forest and woods of Virginia and Maryland, especially. I’ve been really moved by the ecological and geographical literacy of it all.

So, a lot of how I think about the woods right now has me thinking so much about how we talk about not just the conditions of duress folks were under—being forced to speak and transport firewood, for example. In addition to understanding the duress, how do we acknowledge the intimacy of it all? So much of that forms my own desire to steward. This is related to what you and I were talking about earlier: feeling like, initially, the historical walkers in my life were mostly white, and then being like, Wait a damn minute! You’re telling me that the walk that John Muir took through the South or the walk that Olmsted took through the South—both of those walks were in the wake of the walks Black folks had already taken in the opposite direction? And every other direction, too? I was seeing folks like Olmsted and Muir and freedom-seekers like Harry Grimes17 all talking about trees, caves, solitude, and some form of duress. All of them. And they’re all different.

I think about Shade is a place and I’m like, Oh, I think I want part of what those self-emancipators wanted—which was to find some Living Room, to say, I will not spend any more time on this plantation. I know what attempting to escape could cost me. I know the stakes. That risk assessment has been really brilliant to me. The Underground Railroad is mythologized and made into legend, and the more time I spend finding first-person accounts that center Black life and movement, the more woodsy everything is. Folks are just so rigorous. I’ve been pulling out all of these examples in these 2,000 pages I’m reading, and I couldn’t even tell you how many oaks and poplars and pines become a kind of temporary refuge until a Black person decides that it’s time to move. I’ve been really inspired by the cognitive dissonance that a person has to work through in order to get to the next place—and having to decide for yourself, How do I both find some integrity in this relationship to trees or to wood, but, also, how do I move through it? It’s a little confusing for my brain, but I’m like, What kind of relationship is the one in which we both need each other and are companions, but also are open to the point at which we leave each other? Because I’m trying to be here, but I’m also trying to be there, in the life I must make my life.

AMIRIO: I want to touch on loneliness because you keep bringing it up and it feels important to foreground. I don’t know if I have a specific question in mind, but I wanted to name loneliness and see if you could speak more to the place of loneliness within your life and work. There’s something about how you’re presenting loneliness that feels like you’re adding an essentiality to loneliness—which is interesting vis-a-vis this broader moment of post-pandemic societal fragmentation. I think about the U.S. Surgeon General naming loneliness as a pervasive health threat that we should address. In contrast, you’re speaking to some sort of life-giving-ness that loneliness can offer us, especially within the shade, across all registers. Can you talk more about how you relate to loneliness and why it feels essential to life?

MAKSHYA: I really appreciate this question and I appreciate that you hear the loneliness. You hear me say it, and you’re curious to get closer, not farther. I appreciate that because I find that the way that I’m understanding and framing loneliness for myself is about the distance between us, and has a lot to do with this condition of feeling so far from what’s happening around me. When I think about where the loneliness comes from, I think about being a descendant of American chattel slavery, which relied so much on the rupture of connection and kinship. So many of my ways of thinking about loneliness have to do with the Middle Passage and with the trafficking and the fracturing of our family networks and our language systems. And there’s something about what that does to language, what that does to the earth, what that does to our families—all of that is held in the way that I think about loneliness. Even a little bit of loneliness is related to this sense of estrangement.

I think a lot about Saidiya Hartman and the way she theorizes in her book Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route about trying to process what it means to be a stranger. And she’s playing with the words. And when I say “playing,” I mean looking into language with the utmost rigor. She looks at the word “slave” and starts to think about the relationship, etymologically, between a “slave” and a “stranger.” So, what I’m saying to you is that there’s so much about the fracturing of Black life on purpose and by design and what that’s done—not just to Black families, but to one’s nervous system and one’s relational capacity. I’ve watched myself not know how to be here because I’m still in this cycle or that one—that is the loneliness that I’m trying to process. That’s one frame I have for thinking about the loneliness. Or at least one of many frames.

Ashon Crawley is in Virginia and is on the faculty at the University of Virginia. I was reading his book, The Lonely Letters, and somewhere, in an interview or a conversation, he said something along the lines of, “My loneliness will show me the work that is mine.” That idea—that notion of being directed by loneliness and that loneliness is actually something like a compass or something like a tool that can say, You might need to go over there, or you might need to go over there, go in there. Was that an invitation into Shade is a place, to at least say out loud, I’m looking for cues or clues for livingness? I’ve been thinking a lot about loneliness being something that is like a score for a performance and can maybe tell me how to live and not need to resolve it all, but to know how to live inside of it. There are folks who theorize about “the hold”18 and if there’s a way out of it. I’ve stopped trying to redeem my life; instead of there being something to win over, I’m like, I just want the breath back. I think you can hear it.

I’m really moved by Black feminist practice and study and thinking about—what does Ruth Wilson Gilmore call it? She talks about abolition as “life in rehearsal.” Thinking about shade walking and gathering, I’ve thought, How can I practice the kind of intimacy and attention that repairs connectivity? That is also how I think about ecology: How can I recover a sense of place and put myself back as close to earth forms as possible—which might require processing the ways that I’ve wanted to distance myself from the earth and be as human as possible and never be questioned and never be called property and only be called human? And now I’m like, Oh, no! Once again, the flux. What I’m trying to rehearse is not about being a human, actually, but I think it’s something about belonging to the earth again. The loneliness is something that has helped me do that. The loneliness is not something to work through, but something to listen to and just be okay with. Adjusting to that perspective is doing crazy things to my self-esteem.

AMIRIO: There’s something about shade that is demanding for us to sit with our totality. There’s so much around shade being dark and relating to a subterranean part of our lives that we don’t want to pay attention to—that we’re trying to overcome, work through, and fight. Shade provides a beautiful invitation to sit with the subterranean and not see it as something to overcome but as something to be intimate with.

There’s a great piece by Harmony Holiday where she’s talking about James Baldwin as someone who was suicidal and who definitely dealt with loneliness. Suicidality is a part of his legacy and totality that we often don’t sit with. The shade of who he was kind of goes against Baldwin as this champion and wordsmith who could articulate how We feel about race and Blackness. You’re reminding me—us—to walk with the shade of his life and the shade of all of our lives. The totality of our lives, the wholeness of our lives.

MAKSHYA: I adore Harmony Holiday and her work and her person. I have Baldwin’s “Untitled” poem pulled up. It starts with “Lord, / when you send the rain / think about it, please, / a little?” That’s making me think about this closer reading of Black loneliness and the weather, again. When shade got me a bit closer to the atmosphere than I otherwise might’ve gone. But you have me thinking, and especially with Harmony’s work around music and around being in a kind of frequency of Black life, I’ve so often been like, I want to call her one day and just ask her, Could we talk? Because sometimes I hear shade, and I think, This is a soundscape that I’m trying to process, and it carries so much Black life, and so much Black loss. So, I’m thinking about her writing on Baldwin, and I would say he’s a really bittersweet person for me. I’m always looking for ease and looking for relief in his work and really not seeing either very much. I’m looking for him at ease or for him to be writing through the relief. I guess I am looking because I could use his help and wonder. I’ll chuckle and ask myself, Would he have been available?

I have a little list that I wrote down of the people who have been helping me think about the blues as ecological and who are talking about “Catfish Blues,” “Georgia Buck,” “Little Red Rooster,” Ma Rainey’s “Screech Owl Blues,” Buddy Guy’s “Feels Like Rain,” Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s “Didn’t It Rain.”19 All those people who were talking about the flooding in Mississippi or the Great Migration and using owls and the sea as warning signs. I’m thinking about the freedom-seekers, the musicians. It’s you and me and the people in our networks—Zoë and brontë—and all I hear is a chorus of us. I also think about Saidiya Hartman’s thinking in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals around the experiment of living. I’m trying to live in her curiosity around what a wayward life is or can be. Everything is getting so subjunctive to me. But yeah, somewhere in the book, or actually, I think it’s a conversation she’s having, Hartman suggests she could be a Martian. (I really hope I didn’t dream that.) I’m thinking about her and Sun Ra and about this idea of them both being so here but also so otherworldly. When I was with a mentor one day, she asked me, in front of 40 people after I gave a presentation, Do you ever feel like you are a Martian? And everyone in the room was like, How could she call you that?! But I just thought, Oh, she gets me.

AMIRIO: Where I want to end is on shade inequities. I want to end on something material. Going through your work helped me remember how shade is so essential to our lives as Earthlings. But shade has become a luxury in many ways instead of this more democratized thing that we all have access to.

I was thinking of some quotes to orient me, and I jotted down some when I was thinking about shade coverage not being equitably distributed. Not surprisingly, as you know, so many communities on the margins are often subjected to less tree canopy and, therefore, more heat—which feels obviously very important to understand in the scope of a changing climate and a warming planet. I was thinking about this interview featured in Deem in its latest issue. The specific conversation I’m thinking of features Kathy Baughman McLeod, founder and CEO of Climate Resilience for All, who says, “In the US, redlining and discriminatory housing finance practices from decades past mean that many communities don’t have natural infrastructures such as trees, shade structures, built-in water features, etc. And all of this makes those communities only hotter.”

That quote made me think of another about sweat and how sweat is like an index for who has relief and who doesn’t. This second quote is from poet and essayist Anne Boyer in A Handbook of Disappointed Fate: “Capitalism wasn’t just economics, it was a system of organizing lives, and part of this organization was the distribution of suffering, and a subset of distributing suffering was who would sweat more, and where (hot yoga or the bus stop?).” So, again, I’m thinking about shade and inequities, and I’m thinking about your mutual shade efforts. How does your work help inform how we make equitable shade possible? How do we contribute to this cause of ensuring that we all have access to shade as this ecological formation that is life-saving and, therefore, must be evenly distributed?

MAKSHYA: I love that you said “sweat” because it makes me think about Zora Neale Hurston’s short story “Sweat.” In the story, the main character is in this really painful, stressful relationship, in this abusive marriage. I remember the story ends with her waiting underneath a tree and having this temporary relief despite knowing how much is coming up in her inner life. I feel like I really identify with that character and with that kind of resolve. The story ends with a bit of refuge under a tree while all this inner life is just sitting there, pulsing.20

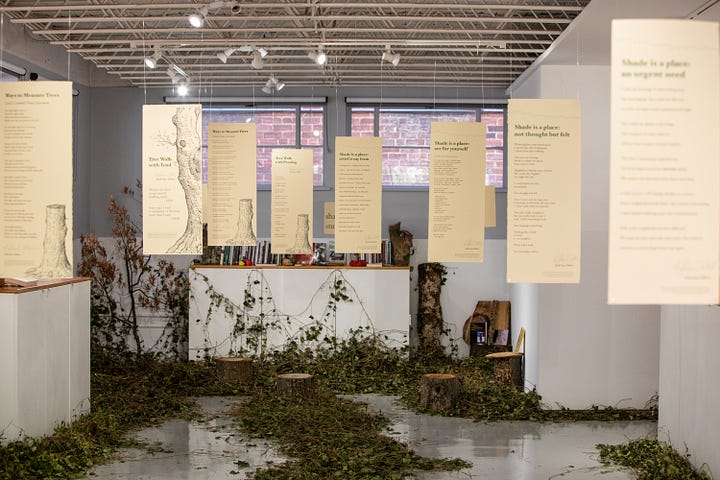

I’m really honored by your question—just by the reference to mutuality and my commitment to seeing all of us in the shade. I had a poetry installation last year—30 poems letterpressed and installed—and a lot of the pieces are in the upcoming book. A man came into my studio one day, spraying something in there—doing some maintenance work. He just said, It’s going to be a long, hot summer. He was just murmuring about what was coming. I was moved by his foresight: It’s March, sir, and you’re talking about the heat that you’re anticipating in June. A Black man, Boomer, in his sixties. But his comment got me thinking about how I could get a bit closer to the material need. His, mine, and more.

As far as my capacity for stewardship goes, it’s been a whirlwind. I got certified as an entry-level wildland firefighter with the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG). I thought I wouldn’t be healthy enough in my body to be there, but hey. Here we are. I worked through a season of training to be both a tree steward and death doula: I am trying to widen the capacity to be an invitation, of many kinds. I spend some time with other volunteers in town working alongside the Rivanna River’s five-mile corridor, as part of a forest health restoration project assessing the density of trees, shrubs, and vines along the river. I’m eager to see our urban forest and woodland ecology come through safely, and in service of our collective livability and safety. Even though some people are mean to me…the vision of what’s possible exceeds them. Like the dream of exceeding the hold.

I ended up fundraising successfully and getting some funding for Shade is a place. I would write in 10% of a grant for mutual shade, and people wouldn’t even ask me what I meant by that. That was the kind of flexibility that poetics can offer. Don’t worry or even ask me what it means—invest in it with faith. I was able to help take on energy burdens—those disproportionate burdens stemming from how much a household invests in cooling or heating relative to its whole paycheck. For example, you may have a family paying $200 a month for an AC bill, but they’re only bringing in $1,200 the whole month. That’s what folks mean by “energy burden.” But, stepping back, I thought, How can I offer relief even if only for a moment—whether it’s only me providing lunches or water or popsicles? Or asking people what they need, whether it’s relational or financial? I’ve been walking with this inquiry that an advisor once offered me: What does it mean to be able to offer what is in my gift to offer, and what is in my gift to offer?

I led shade walks twice a week last summer, every Tuesday and Friday. Meet me on the east end of the Mall and we’ll go westward. But Black folks weren’t coming on my walks as much—and, in general, don’t come Downtown as much, this site that’s really painful in terms of the displacement of Black communities and Black workers. And it’s the site where an auction block was.21 I’ve been really committed to moving money and resources and moving shade and thinking about how I can reach out to the folks who call this Mall their home. So many people are living on the Downtown Mall and are unhoused. Using the capacity of my research funding and the book funding that I got to honor the people whose lives are actually grounded in the site means the world to me. Even if only for a moment.

On my walks on the Mall and on the walks that I’m designing right now, which are tree walks at Court Square, where the auction block was, where the city courthouses were, where a whipping post was, where the marker for John Henry James is—all of that’s there. And the Stonewall Jackson statue was there. I wasn’t here when that was removed. And then there’s Market Street Park, where Robert E. Lee’s statue was. I wasn’t there, either; I guess you come when you come. Those sites are where I’ll lead new shade walks and tree walks. I’ll get to those sites and start walking through the traces and try to figure out if there’s a walk that I can guide that is more loving and less fearful. I think about that also as the equity work of restoring the story of a place and thinking about the Black material life that was in all of those sites. You see the trees and flowers and don’t know that McKee Row was where Black people lived with their locust trees; you just know that area’s office buildings and a bank.22 I will put life where there was life.

MaKshya’s Recommended Resources

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (Saidiya Hartman)

Black Gathering: Art, Ecology, Ungiven Life (Sarah Jane Cervenak)

Jack Whitten: Notes from the Woodshed (Jack Whitten, Katy Siegel)

Black on Earth: African American Ecoliterary Traditions (Kimberly N. Ruffin)

How to Love a Forest: The Bittersweet Work of Tending a Changing World (Ethan Tapper)

Quote from drag queen Dorian Corey in the 1990 documentary Paris is Burning

Excerpt from “Satisfiable,” a poem from MaKshya’s upcoming poetry collection, Shade is a place

Excerpt from the article “Shade” by Sam Bloch

“I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting station, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in.” (Camille Dungy, Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden, pg. 168)

The Unite the Right rally was a white supremacist assembly that took place in Charlottesville, Virginia, from August 11 to 12, resulting in the death of a counter-protester by a white supremacist. Locally, the event has become known as “A11/A12.”

Amirio: You can learn more about the murder of John Henry James, an ice cream vendor who lived in Charlottesville, Virginia, via the Equal Justice Initiative. In EJI’s recounting, I’m struck by the presence of trees: “The white mob threw a rope over Mr. James’s neck and dragged him about 40 yards away to a small locust tree. He protested that he was innocent, but the mob hanged Mr. James and fired dozens of bullets into his body. The Richmond Planet, an African American newspaper, reported that, as his body hung for many hours, hundreds more white people streamed by and cut off pieces of his clothing, his body, and the locust tree to carry away as souvenirs.”

From an excerpt of Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being: “In what I am calling the weather, anti-blackness is pervasive as climate. The weather necessitates changeability and improvisation; it is the atmospheric condition of time and place; it produces new ecologies.”

Amirio: Some additional background on the story from the ACLU: “In the fall of 2006 in Jena, Louisiana, a small town that is 85% white, a series of events unfolded that have had critical consequences for those involved and which indicate an explosive racial justice situation in Louisiana. At Jena High School, students of different races rarely sat together, with black students typically sitting on bleachers and white students sitting under a large shade tree – referred to as the ‘white tree.’ The day after a black student asked the principal for permission to sit under the so-called ‘white tree,’ nooses were hung from the tree.”

Amirio: Here’s a fuller version of the quote from Public Books: “[P]hysical or metaphorical place that affords the space to breathe, to refuse adjustment and accommodation to the demands of society, and to live apart, if just for a time, from the deadly assumptions that threaten to smother.”

Excerpt from June Jordan’s poem “Moving towards Home”: “I need to speak about living room / where my children will grow without horror”

Amirio: The Amenia Conferences “were hosted by the NAACP under W.E.B. Du Bois’s leadership at the home of Joel and Amy Spingarn, longtime owners of Troutbeck [New York] and Jewish-American civil rights activists.”

Amirio: Here’s the referenced Du Bois quote from pre-interview notes provided by MaKshya: “We ate hilariously in the open air with such views of the good green earth and the waving waters and the pale blue sky as all men ought often to see, yet few men do…and just as regularly we broke up and played good and hard. We swam and rowed and hiked and lingered in the forests and sat upon the hillsides and picked flowers and sang.”

Amirio: Whenever this topic comes up, I always have to recognize James Padilioni’s incredible essay, “Cosmic Literacies and Black Fugitivity.”

Amirio: From the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: “Chairman of the Vigilance Committee (part of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society), William Still assisted fugitive slaves as they were secretly shuttled into Philadelphia in the mid-1800s. From 1852 to 1857, Still kept a journal describing his encounters with the slaves in painstaking detail, recording their names, physical characteristics, personalities, and other details.”

Amirio: From John Brown’s slave narrative: “I knew that I ought to go northwards, but having nothing to guide me, I began to look about for signs. I soon noticed that on one side of the trees the moss was drier and shorter than it was on the other, and I concluded it was the sun which had burnt it up, and checked its growth, and that the dry moss must therefore be on the south side.”

Amirio: From The Virginian-Pilot: “For several months, Harry Grimes lived in a hollow tree, likely in the southern end of the Great Dismal Swamp.”

Amirio: From 4Columns: “In the chapter ‘The Hold,’ [Christina] Sharpe traces this word from the belly of a ship via the cops and wardens who enforce the contemporary manifestation of the hold (in a striking observation, Sharpe describes the cellphone picture Oscar Grant took of the transit cop who later killed him as having been ‘shot from the angle of the hold’), to the necessity of, despite everything, holding each other: ‘Across time and space the languages and apparatus of the hold and its violences multiply; so, too, the languages of beholding. In what ways might we enact a beholden-ness to each other, laterally?’”

Amirio: A great companion piece for this list is J. T. Roane’s essay “Tornado Groan: On Black (Blues) Ecologies.”

Amirio: I’m also thinking about the relationality between the character Janie and a pear tree in Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Amirio: From Charlottesville Tomorrow: “In this area, now downtown Charlottesville, traders held auctions to sell enslaved people. The auctions occurred at various sites: ‘Outside taverns, at the Jefferson Hotel, at the ‘Number Nothing’ building, in front of the Albemarle Co. Courthouse (where sales were then recorded), and, according to tradition, from a tree stump.’” (emphasis mine)

Amirio: From Cvillepedia: “By the time it was razed in 1918, it had become a majority-Black residential pocket neighborhood and the lane was known as McKee Row.”

This was an incredible read, and you two are amazing, and PLANTCRAFT is my favorite thing on the Internet.

A spiritual journey!!