Paracelsus (1493-1541), the famous occultist and founder of toxicology, was enamored of lemon balm in his potions. He included lemon balm in a decoction that was purported to be his revitalizing “elixir of life.” This potion was said to regenerate the drinker’s strength and make one almost immortal.1

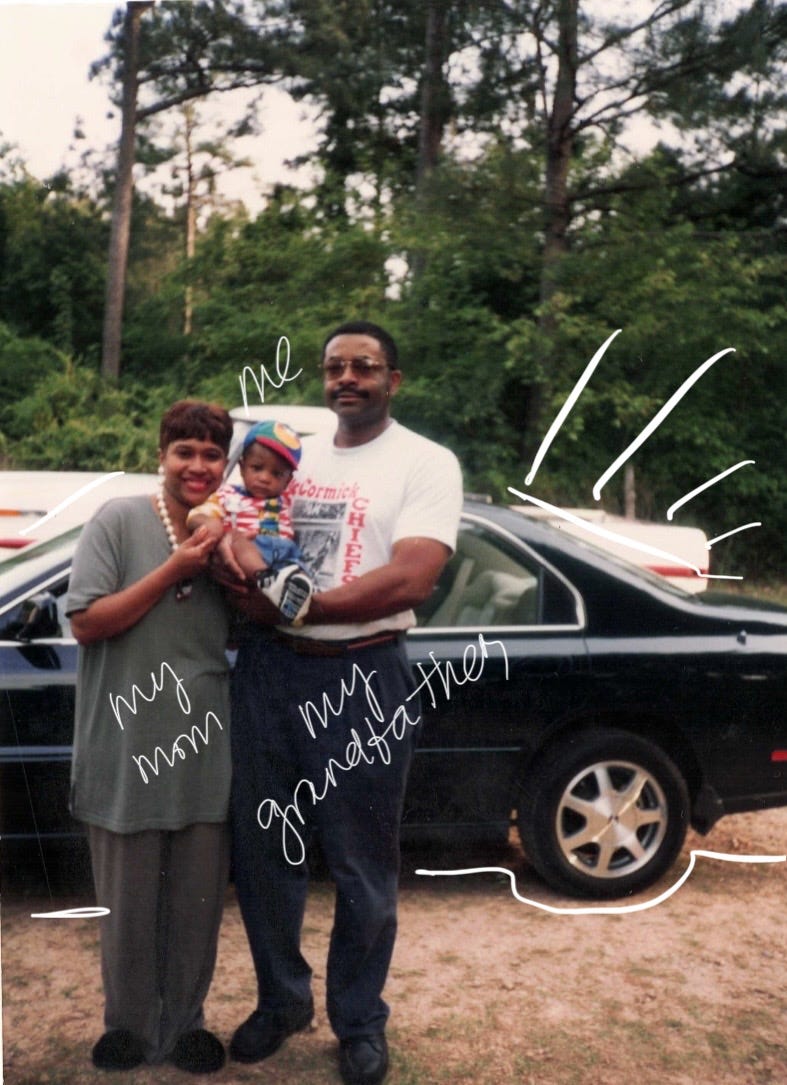

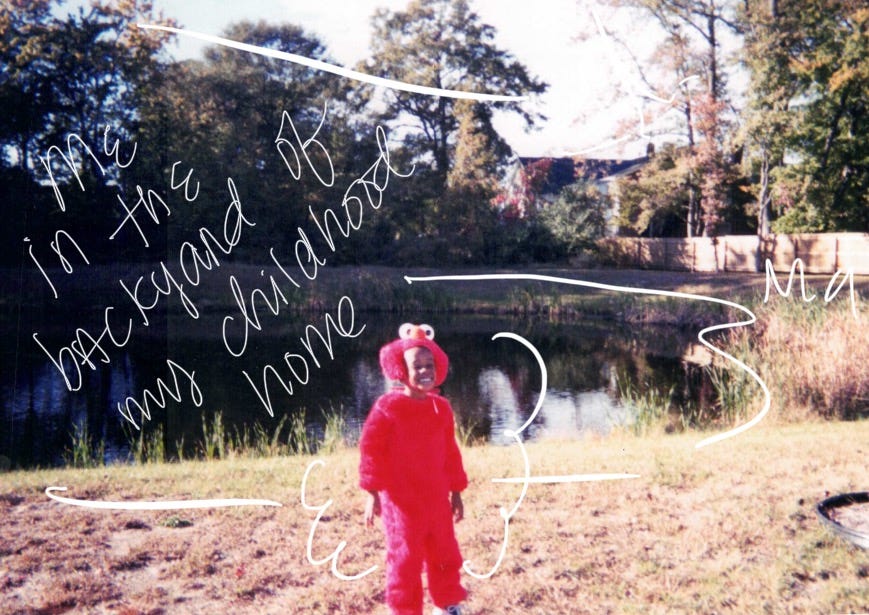

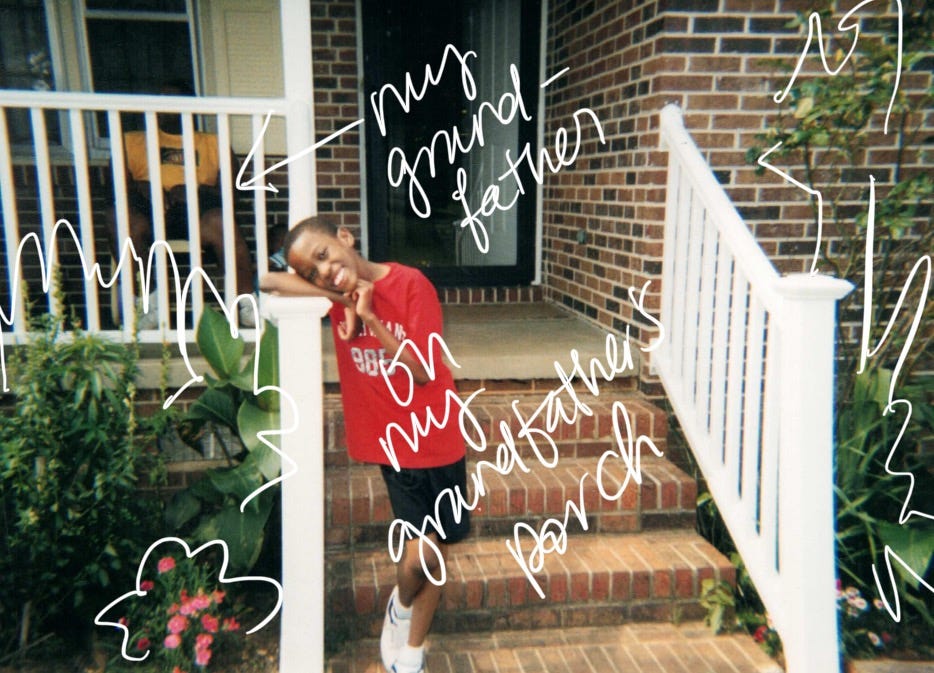

I come from a lineage of folks who are prone to losing photographs.

Among family members, it’s long been rumored that a great-aunt on my mom’s side is the sole custodian of a trove of familial photos going back several generations. For unknown reasons, this great-aunt has chosen to make the photographs inaccessible to our wider family tree, becoming, by default, the lone steward of our kin’s past. Out of a loving, protective fervor? Out of some other obscured impulse? No one is certain. The animating force behind her safeguarding is far less clear than the impact of it: many of my family’s origin stories remain pockmarked and speculative, haunted by buried knowledge of my ancestors’ lives. I imagine all the unseen, untouched treasures in my great-aunt’s home that dust mites, house spiders, and creeping mold use as mere architecture.

The photographic losses in my bloodline continue matrilineally. In one of those rare, sudden moments when a parent exposes their slip of subjectivity, reminding us that parents aren’t just gardened and plucked from a patch whenever a child is born, my mom revealed that a collection of photos belonging to my maternal grandmother was consumed in a house fire. The details of the when and how are lost to me. Still, I invent an inventory of what perhaps fell prey to the flames’ appetite: Auntie V. parading a freshly deracinated tooth; Uncle G. languidly posing in first-day-of-school drag; my mom, the inheritor of my grandfather’s preternatural stoicism, caught in the act of being unbound and irreverent before the sedimentation of adulthood. Years later, in my home state of Virginia, a hurricane flooded the shed in the rear of the home I lived in as a teen. After the surge of wind and water receded, my mom, my younger brother M., and I recovered what was left of our waterlogged photo boxes and other keepsakes. I continue to grieve my family’s involuntary offerings to the elements.

My fascination with my family’s photographic gaps is largely driven by living among forces that gladly and easily make the humanity of many of us erasable and sacrificial. Familial images, in opposition, are one of many artifacts that insist on the humanity of many of us, petitioning for our longevity, endurance, and preservation. Petitioning for us to be strengthened to outlast the longevity, endurance, and preservation of the erasing, sacrificing forces. In our documentary still lives is life, still—despite the death grip of capital and ghoulish abuses of power.

Below is a sample of family photographs I’ve saved through my own record-keeping. Many of them, true to PLANTCRAFT, showcase how the more-than-human world has always been entangled with my labor of living. I pray these and other photos I’ve compiled over time, in albums, on my phone, and across a slew of drives, can be a kind of “elixir of life” for myself and those who will come after me. Looking at these photos, I’m reminded of journalist Ayurella Horn-Muller’s argument that “climate carry-ons,” full of photos and other mementos, should be prioritized alongside go bags and disaster kits in our climate-ravaged times. “Reminding people that sentimental belongings—whether a photograph, a figurine, or an item of clothing—matter too could be a small stride toward helping them recover emotionally after a disaster.” Photos and other material culture as containers of wholeness amid fracture.

The power-hoarders who commandeer so much of our lives are master illusionists: they’re adept at tricks that disappear the archives of meaning and feeling we infuse into ourselves, each other, and the places that claim us. I’m heartened by the capacity of photos—our fossilized memories, the things we save in anticipation of emergency, that we look for in the rubble after disaster strikes—to foreground and regenerate our here-ness over and over, brushing up against something like immortality.

Lemon balm affects the three major seats of the nervous system: the brain, heart, and guts. In all cases, lemon balm soothes and cools overactivity.2

A few months ago, I watched the Al Jazeera-produced documentary The Night Won’t End: Biden’s War on Gaza in the West Philly home of a new friend.

The screening was the anchor event of a fundraiser for supporting Palestinian communities besieged by Israeli imperialists. While balancing a plate of food on my knees, ensconced in a living room with strangers made familiar by the recognition of rage and heartache in each other, I focused on the barrage of images before me: still after still of Palestinians being killed by Israeli soldiers, while seeking safe shelter, finding sweets for small children, and erecting other monuments to life and care; scene after scene of American leaders greasing the wheels of genocide, while talking heads laid bare the mechanics by which an entire group of people can be made culpable for their coerced death. As the documentary reached its end, the experiential gulf between what was captured onscreen and what was happening in real-time in the living room seemed to grow to the size of a canyon, to the dimensions of a dozen universes.

As the overhead lights switched on, the room was guided through a series of exercises for processing our feelings and alchemizing them into action. We practiced mindfulness, bringing presence, focus, and calm to our hearts, heads, and guts. We collected donations and talked in pairs about moments in the film that materialized our unsteady hope and flushes of disgust. In the last moments before the gathering began to dissolve, we sang: a conspiracy of voices conjured the inevitable liberation of a people from colluding empires. Togetherness provided a means for fortifying ourselves and developing attentions and antagonisms muscular enough to counter spectacular scales of devastation. On my ride home, I wondered, What other fortifying tools can and must we access at this moment?

Since then, I’ve turned to lemon balm for its wisdom.

As I’ve deepened my study of how plants have always provided a sturdy foothold during times of human-crafted turbulence, I’ve learned lemon balm has an expansive history of bolstering the body against several conditions that erode and weaken: antsiness, anxiety, dwindled focus, hyperactivity, scorpion stings, sleep deprivation, spider bites, wasp wounds. Writer, astrologer, and herbalist Maeg Keane tells us that lemon balm is also “well-indicated in hot flashes, heat stroke, heat exhaustion, and hot fevers that are unrelenting.” As the collective allostatic load of our species continues to grow, amid the sustained capture of our attention by our digital feeds, amid ongoing climate chaos, amid post-2008 hegemonic crisis in the U.S., amid, amid, amid, lemon balm offers us armor during increasingly embattled times. In this month’s missive, I suit up with lemon balm alongside guest Suhaly Bautista-Carolina.

Suhaly (she/her), Moon Mother, is an AfroDominican herbalist, artist, educator, and community organizer. Her practice lives intentionally at the intersection of plant power and people power and centers the collective wisdom of her community and the ancestral legacy of her people, while creating spaces of agency for folks to enter into their own healing. She is a 2018 graduate of the Sacred Vibes Apothecary spiritual herbalism apprenticeship, and carries out her purpose through small-batch, moon-powered plant medicine offerings, justice-forward collaborations, workshops, knowledge-shares, and beyond. She has hosted plant medicine-making workshops with organizations including Gossamer, The Wing, Creative Time, Weeksville Heritage Center, The Museum of the City of New York, Ethel’s Club, The Highline, and Fotografiska, and currently co-leads an ongoing “Lunar Herbs” workshop series with GoldFeather. She has also guided workshops at the 2nd and 3rd Annual NYC Spiritual Herbalism Conferences. The Moon Mother is a proud member of United Plant Savers and Herbalists Without Borders. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Oprah Magazine, Bustle, and Nylon Magazine, among others. The Moon Mother is living and loving in Brooklyn, on unceded Lenape and Canarsee land, with her wife and their baby girl, Luna.

Amid the vibrancy of a full moon, Suhaly and I dipped into all the sweetness lemon balm has to offer, touching on Western medicine’s indebtedness to vegetal intelligence, the process of excavating familial legacies of botanical entanglement, and the role of lemon balm and other plant kin in the work of revolution. I’m beyond excited for you to dig into this exchange, and I hope you’ll let me know what you think of it. (This conversation took place in August 2024 and has been edited for clarity.)

AMIRIO: I want to start by defining herbalism because I feel like there are so many misrepresentations and misconceptions regarding this practice. Online and during conversations that I have, I think herbalism is seen as this very woo woo endeavor without a lot of substance and heft, especially vis-a-vis more traditional Western medicinal practices and modalities. I’m curious to know what those bad-faith readings of herbalism have been that you’ve had to actively counteract and say, That’s not true. That’s false, and you’re not getting to the heart of herbalism. What have been those narratives you’ve had to address? And again, how would you define herbalism?

SUHALY: Thank you for your question. I know the joke is that colonization is the reason for anything bad. We can say, Oh, this is colonization’s fault, about almost anything. However, it’s interesting that the narrative has been flipped to portray herbalism as something that’s woo woo or less powerful or real or potent than Western medicine because the truth is that a lot of Western medicine gets its “juice” from Indigenous plant medicine. And I’m not talking about “juice” in the sense of cultural cachet or importance. I mean chemistry: Western medicine is really about isolating the constituents of plants, identifying singular properties, and then redesigning them in a lab. After, you’re taking pain medicine instead of taking plant medicine that is analgesic, right? You’re not consuming an analgesic plant, which is a plant that alleviates pain. Western scientists are really just identifying which plants they learned can treat pain, going under a microscope, isolating all of the individual parts of those plants, and then creating something new. When looking at the nitty-gritty of how this all works, it’s always fascinating how the narrative has been flipped so that herbalism is on the woo-woo side when herbalism ignites and fuels a lot of Western medicine.

Throughout my journey with spiritual herbalism, understanding what has happened historically to put a negative spin on herbalism or create this false narrative around what herbalism is or isn’t has been a hard pill to swallow—but it’s not too surprising when we consider colonization and racism and the ways that Indigenous people, cultures, traditions, and medicines have been erased over time. Nothing about this narrative flip seems surprising; it’s frustrating, but not unusual, considering the timeline and our history.

I entered herbalism through a spiritual pathway, which to me is a whole ‘nother arena of herbalism—one which considers the chemistry of plants and the spirit of plants. Our human connection to plants. Spiritual herbalism sees plants as beings—individual beings that we are in community with, in harmony with, on this earth. When studying plants, we’re not just looking at their actions, contraindications,3 and properties: we are learning about those things, yes, and also about the connection between plants and ourselves. What is the spiritual bridge between a plant, as an existing spiritual being on this planet, and a human? Where is their synergy? How are we supporting each other? How does this plant support my heart? How does this plant support my brain? How does my breath support this plant’s life? How does the existence of this plant enhance or improve based on how I behave?

Herbalism is really where Moon Mother Apothecary’s foundational values come into play. Herbalism is about plant power and it’s also about people power. It’s both elements coming together in a way that acknowledges life on both sides—and the inherent fragility on both sides. And it’s about the interdependence between plants and people. Herbalism is Earth science, which is my jam, but also spiritual interconnectedness and the ways in which plants and people coexist and need one another.

AMIRIO: First and foremost, thank you so much for acknowledging how Western medicine is so indebted to knowledge that has been highly marginalized—or even destroyed. There’s a weird contradiction: we’ve dehumanized and delegitimized certain ways of knowing, but we’ve also committed immense theft of and used that same knowledge to inform how we live. It’s one of those irrational contradictions that are part and parcel of the logic of white supremacy and capitalism. There’s so much absurdity baked into their rationales.

I also appreciate that you demarcate the difference between herbalism and spiritual herbalism. The latter seems very relational, inviting us to create intimacy with plants. I’m wondering if that’s a framework that you grew up with, that you inherited, or is that one that you had to come into. To be like, Oh! Plants aren’t just things in the backdrop of my ecosystem, but they are autonomous and have agency and it’s up to me to revere, honor, and build a relationship with them. If you had to learn that framework, what was that process like?

SUHALY: That’s such a great question. I think about that a lot. I often ask myself, Where did this come from?

I grew up in a household that respected and acknowledged the power of plants. So, growing up, if a fever broke out or there was some sort of illness—my mom’s first instinct was to go to the plants she knew from the Dominican Republic, the plants that she had access to, and the plants that she knew how to work with.

From a very early age, I was taught that our first instinctive healer is the natural pathway. That idea must have shaped my long-term relationship to plants. I have developed respect and reverence for plants and have learned that they can do more than just “be there”; I have come to understand that plants have purpose, are unique, and each plays an individual role within our world and within our existence. I felt lucky that we had access to them.

I talk about this a lot, but I grew up between two urban parks in New York City. Even though they are essentially man-made parks, over time they have evolved into unique ecosystems, with migratory paths that have been created for specific species of birds, for example. When you build a place, it becomes its own environment. That has happened, and I felt privileged, even as a young girl, to be in such close proximity to nature.

There was a combination of things happening that influenced me: seeing the way that plants were being utilized in my home, having access to green spaces and parks and landscapes that were important to me, and where I learned power resided. Later in my life, when I could make choices about what I wanted to do and the practices that I wanted to undertake and the skill sets that I wanted to sharpen, it was natural for me to want to lean into the study of plants and develop a deeper understanding of what plants could do and how I might be a conduit and resource for my community using the wisdom and medicine of plants.

AMIRIO: I would love to hear more: could you share a series of moments, or just one specific memory, that provides an example of how you saw specific plants being used while growing up?

SUHALY: I have two examples! One I always remember involves oregano.

AMIRIO: Classic! She’s a classic girl.

SUHALY: She’s a classic girl! Dominican oregano is a unique species. I have to look into that more because I don’t have that much information, but I know that every time somebody goes to D.R., they’re like, What do you want back? And I’m always like, Oregano! I don’t want anything else. I just want you to bring me back oregano. At home, I have a big box. I always have a very big stash of oregano in my kitchen.4

I remember my mom using oregano for stomach aches—boiling the oregano plant in water, simmering it. And drinking it was terrible. (laughs) This is not something that is going to be delicious by any means. But that’s a plant I distinctly remember my mom leaning on. And then there’s Dominican onion tea. You can Google this.

AMIRIO: That also sounds a little pungent!

SUHALY: But you know, this one actually can go down smooth because it includes other delicious plant allies like star anise, cinnamon, apple, onion, honey. The onion is definitely still there—

AMIRIO: —But it’s undercut!

SUHALY: By using so many strong, aromatic herbs, you can cut the taste of the onion. The tea is the flu killer in a Dominican household. It’s something that a lot of Dominicans grew up drinking. And I love that we share that recipe; even with its variances across households, it is a staple. And I wonder if my Haitian kin have a version of that tea because we grew up on the same island.

AMIRIO: Our cousins throughout the diaspora—we be doing the same thing.

SUHALY: Yeah! There must be a counterpart to Dominicans’ tea. But, overall, those are some of the moments I remember. I still make those teas on my own. Those plants are still very much a part of my life and herbal practice.

AMIRIO: I want to get into motherhood. I love that one of the memories you mentioned is associated with your mom, and I love how mothering and motherhood are such vital parts of who you are. Your herbal practice, Moon Mother Apothecary, has “mother” in the title, and the logo features a pregnant individual. You're also a mom; you have a daughter, Luna, who you often mention.

In one interview that I love for the anthology So We Can Know: Writers of Color on Pregnancy, Loss, Abortion, and Birth, you talk about motherhood, specifically in a queer relationship. There’s this beautiful part where you talk about how you’re preparing Luna to be ancestrally oriented:

I am satisfied with what she already has and knows and holds and carries, and I think about the way that I build altars in my home a lot and how we honor our ancestors in my home. I bring her into ritual so often and she is such a natural participant in all of those things that I know that what we practice is part of her already.

I appreciate how you're equipping Luna to have her inheritances be embodied. Thinking about mothering, lineage, and ancestry, I’d like to know, beyond your mom, who are those blood and non-blood elders and ancestors you’re drawing upon to inform your work? And how are you passing on these botanical and herbalist lessons and worldviews to your child?

SUHALY: This is so important! Even when I talk about where my connection to plants comes from, there are connections that I don’t know about. There are connections that I’m unaware of that exist inside of me, that are in my bloodline, that are in some part of my lineage. I’m confident that specific ancestors have carried this responsibility of being the medicine woman or medicine person in their community. I’m clear on that. I may not have the exact names, neighborhoods, or lands that these people lived on, but that doesn’t matter since I’m living in my purpose when working with plants.

Plant wisdom and understanding feel very innate and natural for me—and I think it’s the same for Luna. I know her connection doesn’t just come from me. Part of it does, and this is the whole nature versus nurture component because I feel like she is practicing what she sees and understands the value of plants as she grows. Building kinship with plants is something that is important and powerful for our family. It is a value.

But I think there must be something deeper—something ancestral—that is a part of Luna. And so I let that do its own work. I don’t need to go too hard. She is all set. She came here with her own relationship to the earth and plants and other beings—and I can hear it. I can hear it in how she talks about the earth. I can hear it in how important animals are to her. I can hear it in how she talks to and about plants and flowers—which she’s been doing since a very, very early age. And so everything we do in our household is just an amplification of what she already came to the earth with and knowing.

Being a mother feels so powerful as an identity for me and is a role that I take seriously, because I became an herbalist as I was becoming a mother. I found out I was pregnant two months before I started level one of my spiritual herbalism apprenticeship at Sacred Vibes Apothecary with Master Herbalist Karen Rose—one of my living teachers and role models in this practice. Another important individual is my grandmother, who passed before I was born. I see her in my dreams. In my understanding of her, she is someone who was and is connected to plants. When I talk to my mom about her, I get little snippets. It’s hard to extract stories from your living family, especially when those stories connect back to trauma, and so, sometimes, it’s difficult to get all of the details. However, from my understanding of who my grandmother was, I sense that the living world outside of humans was important to her, that landscapes were important to her, that her garden was important to her, that she tended to her flowers with care and devotion. I’m like, Okay, I understand who she was and what was valued by this person who tended to a garden and had certain flowers. So, my grandmother’s life is a connection that I honor and try to talk about often so that it stays alive in me and my memory and my imagination and my honoring and my altar.

Those are some examples of ways I am modeling what it means to honor your lineage, even when you don’t have a lot of information about who the individuals in your lineage were, and are. You can still acknowledge that you come from a people with a practice, and at some point, before colonization and before white supremacy, your people were connected to landscapes. And you can go back to those places. Luna’s been to the Dominican Republic a few times, and we talk about what we see. We spend as much time as possible in our homeland to inspire a connection to a place with which she can have a long-term relationship.

AMIRIO: What makes the work that you’re doing so special is that you’re being such a diligent custodian of your own archive—one that Luna will have to know she has a lineage. She can investigate her relationship with the more-than-human world and say, Oh, it didn’t start with Suhaly. You’re providing a starting point for digging into the past through what you’re saving: all this information, these anecdotes, these artifacts. And I love this moment of you being like, Oh, I have clarity around my purpose that’s tied to my ancestry. When did that aha moment happen? And bringing in lemon balm, our focus plant for this conversation, how did that botanical become folded into that aha moment and your broader journey?

SUHALY: I don’t know if there was one moment, but there were many smaller moments. Many breadcrumb moments led to this place of knowing, It might be time for this journey to begin. It’s funny because me and Karen [Rose], who ended up being my teacher, had been circling the same circles for a long time, bumping into each other at places. I knew a lot of the herbalists who had graduated from her program, and I had conversations with those folks. These moments kept happening where I had one foot in and was in the stratosphere but not deeply at the center. And there came a moment where I had to make a decision. I remember having a phone call with a good friend named Adaku Utah, who co-runs Harriet’s Apothecary. I remember them saying, You have to make space for this in your life. If you feel you are ready, you must make space for this in your life. I had to really sit with that. I thought, That’s a good piece of advice. It means my whole world will be transformed by this decision. And it has been.

It was such a great invitation to ask myself if I was ready: if I was prepared to evolve, if I was ready to acquire a skill set that came with a set of responsibilities, if I was ready to be seen by my community as someone who could support them on their healing journeys. There were all these—I don’t want to call them “implications”—but all these residual impacts that came with becoming an herbalist. Wonderful, wonderful ones, and also big ones—big heavy ones. When I entered into my practice, I was like, Now I understand what this means and who I need to be. I have to be different. I must be different. I was being called to an honorable role: one that’s well-respected traditionally in our Indigenous spaces, in our Native spaces. A very important person in our community is a person who holds the wisdom of the plants in our religions, in our spirituality, in our stories, in our myths. A person who knows that nature has a lot of answers, has a lot of wisdom.

All of that was part of my journey—of coming to a greater understanding, layer by layer by layer, of what it means to step into being an herbalist and be comfortable in that role. And also of letting the role be what it is going to be for me and not allowing other examples of what herbalism is or looks like to taint my understanding of my unique place in herbalism—which is why becoming a mother as I was becoming an herbalist was such a unique and powerful intersection that happened for me in my life at the time. I knew how herbs supported me in becoming a mother and that was something that I wanted to share with other people; I wanted to be there to support people who were becoming mothers, alongside new mothers or caregivers and people who were in a mothering role. That became very important to me.

It’s funny that we’re talking about lemon balm while there’s a full moon. We’re on the second day of the full moon in Aquarius—a supermoon, blue moon, rare moon.

AMIRIO: I saw her last night and I was like, The moon got a BBL! She’s looking juicy!

SUHALY: Hilarious! Yeah, it was really beautiful last night. And it sucks that you can’t take a picture of the moon. She’s just like, Real eyes only.

AMIRIO: Demure!

SUHALY: Demure! Very demure. But I love her. Within my spiritual herbalism practice, there’s a plant that I had to walk with in my first year. There’s a plant that you journey with that you learn inside and out and that you work with and make medicine with across your study. I walked with violet my first year, which provided so many lessons, so much beauty—and pain and understanding. It was such a beautiful experience.

And in a way, I was also unknowingly walking with lemon balm. She was the other plant that I was gravitating toward. So much so that during my culminating project, nearly every herbal recipe I developed had lemon balm.

AMIRIO: Haunting you!

SUHALY: It was just like, Hi, I’m here! Why not pay attention to me? Hi, it’s me. Then, lemon balm came to the center more when I acknowledged how supportive that plant had been for me and how much I relied on that plant to give me comfort and to sleep. To provide ease and help me through my anxiety and postpartum depression and just all of the things that I needed it for. It was this constant hum that I eventually acknowledged by saying, Hey, it is you. You are the star. From there, I had more intention with the medicine I made with lemon balm; it came to the center more clearly.

It’s also such a beautiful herb for kids. You don’t usually work with mints for kids because they can be too spicy, and younger kids don’t often like their taste. (Children might be reminded of toothpaste or something.) But I worked with lemon balm a lot for Luna. In a sense, Luna has always been taking herbal medicine: she was taking herbal medicine in the womb when I was taking herbal medicine. When I finally started to give her teas and tinctures, I think lemon balm was the first herb I ever gave her—lemon balm with chamomile. I made a lemon balm glycerin, and Luna and I would take it every night. We would take a few drops each evening, and it became a family ritual.

We were packing to go on vacation this week, and I was like, Cool, you have to write down all the things that we can’t forget. And Luna included lavender and lemon balm on her little list. I’ll take a picture of it and send it to you because it’s so sweet that she was like, We can’t go anywhere without my lemon balm.

AMIRIO: She was like, I gotta keep that thang on me!

SUHALY: How am I going to sleep, and what if I get sad or anxious? I love that. I would call lemon balm our family, household herb. Especially for New Yorkers, lemon balm is the best; it’s the exact thing we need. It’s an herb that is soothing and calming and mothering and is the light in the dark. That’s how I feel about lemon balm: it is the light in the dark. When I learned about lemon balm, I remember Karen [Rose] saying, Lemon balm is a full moon over the ocean.

When my partner and I were naming Luna—Luna’s always been my choice of name. Since I was young, I have been like, Chile, if I have a child, their name will be Luna. And the other name was Violet. This was locked in before I was even an herbalist. But, my daughter’s name is Luna, and her middle name is Kai, which means “ocean.” So, early on, I’m in herbalism class and I’m studying all of these plants, including lemon balm. I’m thinking about what my child’s name is going to be. All of this wasn’t intentional in the sense that it was planned, but there was some intent regarding the presence of lemon balm in my life—and in Luna’s. She has this relationship with lemon balm that she can acknowledge—that we all can acknowledge. Luna’s always like, I don’t want to leave without my binky, my plants. Lemon balm has played a beautiful and constant role in our lives, and it’s an herb we can depend on. It holds a really special place for us.

AMIRIO: I love that you described lemon balm in so many ways, including as an herb that can be mothering. I want to stick with that because the idea of a mother is very zeitgeisty right now. We’re all like, Oh, you’re mother right now, when someone is serving. In this moment of polycrisis, we’re all thinking about how we mother a new reality, a new world. And many of us are interrogating how to be more caring and become mothers in terms of enacting and providing more nourishment and tenderness. It feels like we’re in this moment where mothering feels very resonant, very prominent. In the obvious ways and beyond them, how are you mothering right now, and how has lemon balm been an ally amid all the different ways you’re mothering?

SUHALY: That’s great! How am I mothering? There are so many ways that I think of motherhood, but one of the ways that’s really present for me right now is the mothering of the self and how necessary that is to care for anyone or anything else. I remember my herbalism teacher, Karen, once asked my class, If your cup is full, can you then give from your cup to another cup? And we all were like, Yeah, because my cup is full. And she was like, No, your cup has to be overflowing before you give to another cup because as soon as you give to the other cup, then yours won’t be full anymore. And I was like, That is such a wild twist on the idea that as long as my cup is full, I can give. We spend so much time trying to fix or challenge issues—and there are so many to tackle daily. When we choose to engage with these very big problems, we often forget to consider how we are going to restore ourselves after we’ve submitted ourselves to so much pain and trauma.

AMIRIO: It’s about longevity. How are we going to fortify ourselves?

SUHALY: How do we fortify ourselves? We often don’t have the tools or the knowledge or the skills or even the understanding that is needed within us because we’re just running and running and running and running. And then running becomes normalized; we’re just so overactive. Lemon balm is vital because it is a nervous system plant. It is doing the work of mothering one of the most important systems in your body, your nervous system. It’s supporting you and regulating your nerves—your being, your self.

I made a cup of lemon balm tea before we sat down so that I could be with this plant as we spoke. That was an act of self-care and self-love—just being with this plant, revering this plant, and treating myself with as much respect as I have for this plant by saying, Let’s be in community together. Let’s be in this relationship together. Let’s hold hands as we enter into this. That’s such a compass for me as I move through the world and try to understand how plants can be part of this revolution, this new world, and this new reality we’re trying to shape. And to me, there is no new reality without us having a healthy, interconnected relationship with plants. That connection must be part of how we're shaping this new reality. We need plants, and they need us because Earth is mother.

AMIRIO: Literally, in all the ways!

SUHALY: Earth is literally mother in all the ways! It is the vessel, it is the container, that holds all life. We are waking up to that fact in a disruptive way. I think, unfortunately, what has to happen for humans to be fully tuned into our reality is having the things we love—the people we love, our comforts, our luxuries—be taken away. And that’s happening. And it’s happening at such an alarming rate. This next generation is not playing with us. I can tell you that from experience.

AMIRIO: They’re on our asses!

SUHALY: Move over because you fucked it up. We need to support young people. We have to raise children who value and revere the world they live in and who see it as a privilege to be among the plants, flowers, and the earth that feeds us. If they don’t understand our relationship with the earth and feel disconnected from it, then they will see no harm in completely disregarding that component of our lives. I was talking to my friend, and they were like, The orcas have been organizing for a minute.

AMIRIO: The orcas said, If y’all don’t want to run this shit the right way, put us in charge.

SUHALY: Rally the troops! We should see ourselves as part of that. We should be like, Let’s go, orcas! I want an orca tattoo at this point because we are on the same team. They’re leading the way. In my vision—in my Afrofuturistic vision—for us, there is a deep, interconnected relationship between humans and the natural world. There must be. It’s the only way that we’re going to survive. And lemon balm is one of those powerful plants that helps me remember that I must be whole as I enter the chaos at our door. I must be whole and continue to make myself whole as I continue to be impacted by what’s happening in our world. I must return.

I’m reminded of the moon cycle and the relationship between lemon balm and the moon. When we get to that new moon, there needs to be a return to self. There needs to be a new commitment to making ourselves whole again. If I don’t do that, how can I be the light in the dark? How can I get back to the place where I am a resource, where I am a person you can come to? How can I return to where I am a community medicine person? Because we’re going to need every role that we have: we’re going to need the archivists, we’re going to need the children and the visionaries. We’re going to need the architects and the organizers and the orcas and the plants. We’re going to need every force—every life force— available to us to fight the evils we are seeing.

AMIRIO: Continuing to think about mothering, I keep thinking about the genocides we’re bearing witness to, particularly in Palestine, particularly thinking about Palestinian children. And I was thinking about some words written by writer and perfumer Tanaïs in a piece about why they decided not to have kids. At one point, they say:

Today, we’ve seen more dead children than should ever have died by violence. Everything—my writing, my relationships, my future—has been altered by witnessing this. Thousands of families wiped from humanity. Newborns smoked to ash by bombs made and paid for by this land of my birth. Their only crime: being born Palestinian. Every video echoes in a dormant maternal hollow inside me, unfulfilled by my own body, where I have wept and wailed for these loves and futures extinguished.

I want to return to your idea of bridging plant and people power: how can those two forces combined help us navigate this planetary moment? And what is lemon balm’s role?

SUHALY: As a Virgo, my intuitive starting point is thinking about the herbs literally showing up at the revolution. They must, right?

I remember being part of the collectives that were showing up to protests and vigils and actions that happened after the murder of George Floyd. And I know there are many herbalists who precede me in terms of ensuring that herbs are present for the revolution—through making herbal medicine those on the frontlines need. Making eye washes, making herbal teas for anxiety, depression, insomnia—the kinds of ailments we were suffering from by needing to be present for different justice actions. There is a role for plants in the landscape of movements for liberation.

Early on in my practice, there was an intersection between plants and people that I wanted to play in, that I wanted to be in, that I wanted to practice in. How are we going to show up when the revolution’s at our door? Where will the plant people be? Where will the plants be? I wanted to be in that space. And luckily there are so many other herbalists and plant people and farmworkers who are working at that intersection with me and doing critical, necessary work.

In terms of motherhood and this moment, there’s part of me that feels that we need to witness what is happening with open eyes and awareness to understand how we have failed mothers and children across the world. We need to sit with the ways in which we have chosen other comforts above life, and above the bodies that can give life. I’m naming mothers, but I’m really talking about life-giving vessels overall—however they wish to be named.

My hope is that we never allow ourselves to go back here and that we will see this moment as encompassing some of the greatest horrors of our lifetimes. My hope is that we will vow never to slide backward into this reality ever again. And that there will be new commitments made, and that there will be new relationships forged across these imaginary lines that have been drawn across lands because of all the things that we’ve talked about—white supremacy, colonization, addiction to war. I hope these times will not become the legacy humans leave on this planet. We all know the earth will be fine; the earth is regenerative. We need to find our place because we’re the ones at risk. Our existence is at risk.

Lemon balm can be a way to help us see our power, to help us see the mother in us, the caregiver in us, the nurturer in us. My relationship with lemon balm was oriented around me for a long time: it was just about restoring my vitality and making myself whole again. And then the relationship came to include my daughter and making sure that they feel calm and held and nurtured before they go to sleep. Lemon balm provides the safety and comfort that a mother can provide. The plant says, Work with me to make sure that this child feels good and calm and held and loved and sheltered from threat and pain and trauma and nightmares and all of the things that children may be worried about, especially at this time. All plants play unique roles in this moment, and learning about them in a deep, concentrated way feels like such a gift. Because when we study plants, when we take a year or a lifetime with a plant, we can uncover so many layers of its life and purpose. It’s similar to how you don’t learn who someone is in a day. You spend time with them, watch them in new conditions, and see how the seasons change them and how they affect one person versus another. If we treated plants like we treat the people in our lives, we could learn so much more about them and what they can do.

Suhaly’s Recommended Resources

Podcast: How to Survive the End of the World — Witch School Chapter 16, Suhaly Bautista-Carolina

YES! Magazine: “Murmurations: Experiencing Urban Earth Beauty”

Learn More About Suhaly’s Work

Saturday, November 16 | Herbal Saturdays at New York Botanical Garden

Sign up for Suhaly’s newsletter, The Last Quarter, here

“Lemon Balm: The Immortal Life of Bees,” Jessica Peterson (emphasis mine)

“Jupiter’s Lemon Balm,” Maeg Keane (emphasis mine); big, big thanks to Bitter Kalli, new friend and the mind behind one of my favorite newsletters, groundwater, for suggesting I read this piece

Amirio: In this context, contraindications are circumstances under which herbal medicine should not be taken (e.g., during pregnancy).

Suhaly: I keep it stored in a bottle of sazón, which is the gag!

Gorgeous! As always.

Thank you for inviting me to this beautiful conversation<3 <3 big love + lemon balm forever xoxo