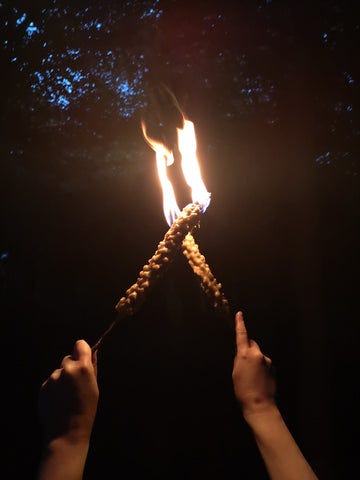

In ancient England it was believed that those who ‘trafficked’ with the devil used dried mullein stalks, dipped in tallow, to light the orgies of their ‘witches’ sabbaths. In other areas mullein was thought to drive away evil spirits, and in southern Europe, mullein torches were formerly burned at funerals. In India, some considered mullein a sure safeguard against evil spirits and black magic.1

Similar to kudzu, mullein embodies humans’ impulse to regard more-than-human life as Janus-faced— virtuous and Devil-dancing by nature.

Mullein has been part of the theatre of our lives as far back as ancient times. The plant has been cast as both nemesis—a pesky weed that stalks roadsides and disturbed areas, a prop for wicked acts—and an essential tool tapped for everything from coping with respiratory illness to lining shoes to predicting the weather. Continuing PLANTCRAFT’s interest in exploring the limits and loopholes of human perspectives when it comes to relating to our botanical kin, I explore the cultural dualisms tied to mullein with this month’s guest, Ashia Ajani.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Ashia is a sun shower, an overripe nectarine, a carnivorous plant, a glass bead. Hailing from Denver, CO, Queen City of the Plains and the unceded territory of the Cheyenne, Ute and Arapaho peoples, Ajani is the author of one poetry collection, Heirloom (Write Bloody Publishing, 2023) and a forthcoming collection of lyric essays, Tending the Vines (Timber Press, TBA). Her writing is a kaleidoscope of her work as an eco-griot and abolitionist.

In this broadcast, Ashia and I dig into mullein’s many lives, how our plant allies can help those in the U.S. brace for the impending era of mass medical neglect, the (in)visibility of rage in the Black ecopoetic tradition, and the usefulness of language at the end of this world. Let’s get into it! (This conversation took place in March 2025 and has been edited for length and clarity.)

AMIRIO: When preparing for this conversation, I was like, Okay, I feel like the idea of language feels potent and keeps coming up when diving into Ashia’s work. So, I want to think about language with you: what are its possibilities, what are its pitfalls? What are the ways in which language isn’t adequate and is limited?

I first came to your work by way of Heirloom, your debut poetry collection. I had seen it everywhere, and it had been recommended to me a few times. A big throughline in Heirloom is the intimacy between Black folks and the more-than-human world. When you were growing up, how was the more-than-human world understood through language? What words were used, what phrases were used? And how did that language inform how you related to our beyond-human kin?

ASHIA: I grew up in Denver, Colorado. At one time, the Black population was a little over 10%. It’s since gone down. My mom came to Denver for work. She was the first one in the family to leave Detroit, but I don’t think folks were surprised.

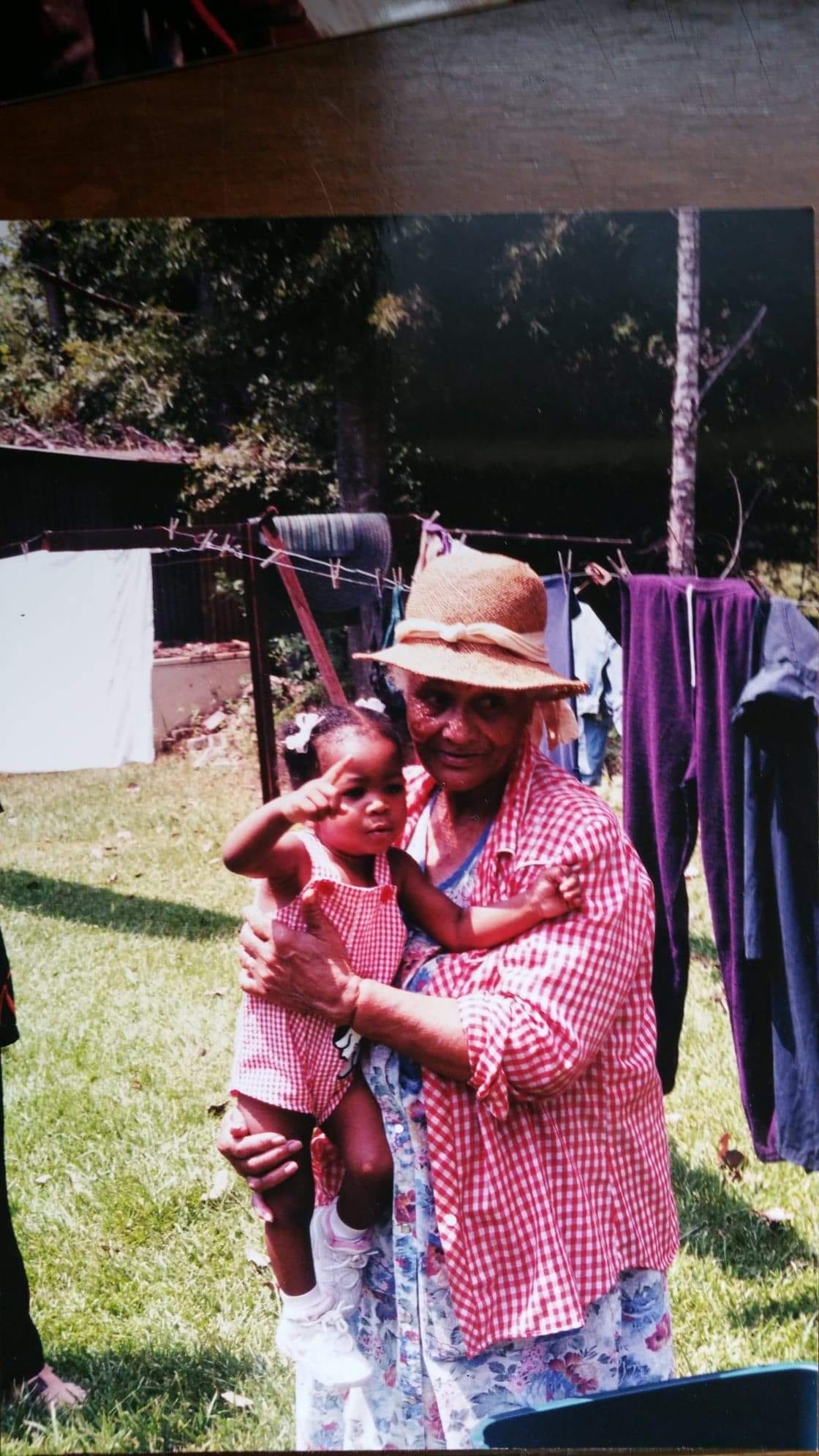

She grew up in Detroit during the riots, white flight, and a lot of racist removal and upheaval. She always maintained a connection to the South. Her mom—my grandmother—is from Bentonia, Mississippi, so my mom spent a lot of summers going down to Mississippi and riding horses, being on the farms. It was a different way of life than in Detroit in the 60s and 70s.

During its industrial and post-industrial eras, Detroit became a graveyard in some ways. And my mom was surrounded by that: Black social and ecological stagnation. Outside of visits to Belle Isle, there wasn’t much access to nature when she was living there. It was very urban, in the city center. She always looked forward to going down to Mississippi in the summers because she could be around the greenery and she could be on the farm and she could milk cows.

I think one of the reasons she moved to Denver was because she wanted to be in a place where there was nature. She tells me—and she tells me this every single time we go on a hike or we go outdoors—that indoor plumbing is one of man’s greatest inventions. She likes the outdoors but with modern amenities. With Denver, she’s had a really great balance.

For a moment, she considered staying in Louisiana where she did her residency. And she considered Atlanta, Georgia, where her brother, my Uncle Waverly, has a dance company called Ballethnic—but that was established a few years after her decision not to take a job in Georgia.

There’s a lot of trauma associated with the South. It isn’t all peaches and cream down that way—just like it isn’t always peaches and cream up in Detroit.

My mom was part of this big Black exodus to Colorado that I learned about in college. During the 70s to the 90s, a bunch of middle-class Black folks were moving out to Colorado—especially to Denver, because it was a newer city where you could get a good union job. You could get a job with a pension, and people were encouraging folks to move out to Denver to create this new Black community.

My mom’s relocation was an example of inventiveness and innovation, which is very much a Detroit thing—because of the ways that white flight and racial terror have shaped Detroit. People there have had to get inventive with the way that they live and the way that they survive and persist.

When thinking about these memories, the more-than-human world was very much a part of my upbringing, even if just through hearing stories.

I split my time when I was young between my granny’s house and my mom’s, and my grandma was very old-school. She was like, You can watch one hour of TV a day if you are not reading. If it’s warm enough out—and even if it isn’t warm enough out—you’re going to bundle up, and you’re going to go outside.

Through my grandma encouraging me to go outdoors, I developed a curiosity toward the earth. I would say, Oh, well, why does this bug like this plant so much? And why is this patch of flowers doing better than this patch of flowers? Why are all the stray cats wanting to come back into our yard? Oh my gosh, there’s a fox den. I had a lot of wonder around the natural world, and it was never spoken about negatively.

My cousins would come and stay with me during the summers, but I was an only child, so imagination was really how I entertained myself. I was my grandma’s baby, but even grandma needed grandma time. So she would bundle me up and send me outside. We had a nice little backyard, and it was there where my imagination sparked. I was talking to trees and I was talking to bugs and I was saying, Oh, I found a little fairy—and it was a dragonfly. A lot of the language I had regarding the more-than-human world was invented through me and my deep engagement with nature.

Again, my grandma is very old-school. I think she saw what was happening with a lot of my peers during the early era of computers, during the early 2000s, and she was like, I want my grandbaby to have a childhood that’s akin to the one I had—because I know what I am capable of. I know my imaginative and creative power. I think she wanted to transfer those abilities to me.

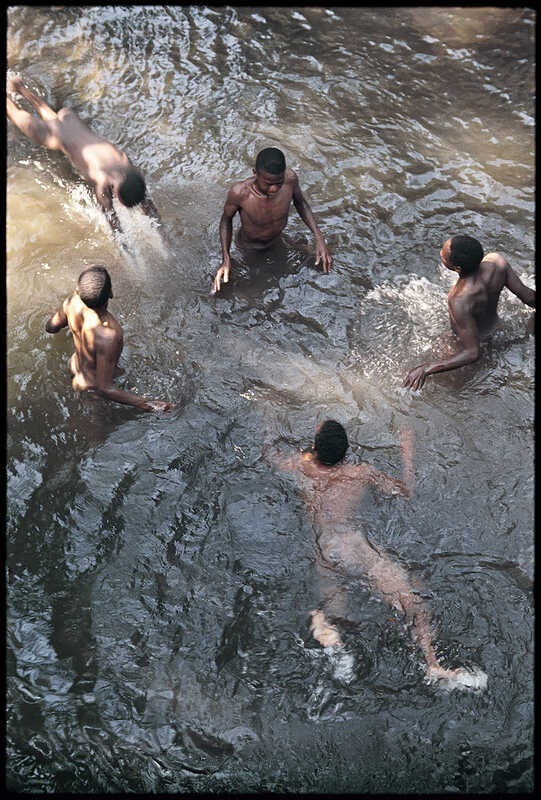

When I started reading seriously about the idea that Black people don’t like being outdoors, it was a very foreign concept to me. Even when I went to school, I remember some of the girls on my basketball team and some of the girls that I would hang out with saying, Oh, yeah, Black folks don’t like to swim. I was kind of confused. I was like, But I’m Black, and I do those things. It was confusing until I was able to talk more with them and do more research and reading and understand, Oh, there are intense histories of trauma around these topics and longstanding histories of exclusion and violence.

AMIRIO: I love that your orientation towards the more-than-human world is one of speculation, play, imagination, and wonder. With that orientation being so innate for you, what are practical ways for others to also adopt that posturing of enchantment and awe?

ASHIA: That’s a really heavy question—and something that I think about a lot.

I recently transitioned into a new job, so I’m not working as directly with young people as I used to. But when I was working with young people, oftentimes, it would be my Black students who were a little bit more hesitant.

I coordinated garden education, which involved a lot of planting, a lot of weeding, a lot of outdoor stuff. Black youth are funny and they got jokes and they would be like, My ancestors already did this. I don’t want to be doing this. I understand that humor as a deflection to a certain extent. But then I’m also like, Okay, let’s pause. Why do you feel that way? Yes, okay, it’s a funny thing to say. And there’s also this sobering truth within that sentiment. What is it that is inhibiting you from engaging? What can we work through?

Sometimes, the Black kids I would work with would pause and they’d say, Oh, well, I don’t know. Other times, under the “I don’t know” was a sense of, Oh, I just don’t want to do it. I feel like I can’t do it. I feel like I’m going to be doing something wrong. Especially when Black youth are so overpoliced and over-disciplined, any sort of activity that could be subject to scrutiny is very triggering for them. They’ve had experiences that are so different from those of a lot of students of other races in the classroom.

In the Bay Area, Black youth go into a lot of classrooms with their guard up because they know how they’re going to be received. There’s a wall that you have to work through and break down. And that process can be powerful for young people—even if it takes a while. Sometimes, the process is weeks-long; sometimes, it’s a month-long process. Sometimes they only want to start engaging at the end of the year.

The kids see me working outdoors, and sometimes they’re like, Okay, well, maybe this is something that I could get into. Or I’ll hand them a plant and say, Look, we have this blueberry bush. Do you want to try some blueberries? And then I’m like, Isn’t that cool that we grew this together? A part of my work is modeling and leading by example.

Especially for youth, there needs to be an understanding that these issues aren’t going to get addressed in a short time period. You can’t say, Okay, come to the woods with me and we’re going to hash this all out. There’s a step before we go to the woods.

I love to do urban plant walks so you can see the life all around you. I live close to this place called Lake Merritt in Oakland, which is a popular spot where you can see eucalyptus trees, oak trees, peppercorn trees, lavender, the lake itself. There are so many different birds. During the walks I’ll ask, What do you see? What do you notice?

Through the walks, we can start thinking about some of the ways that we want to engage with nature. What are some of the things you’ve always wanted to do? Oh, well, I’ve always wanted to go hiking, but I don’t have anybody to go with. Well, let’s fix that. I really want to go to the beach, but I don’t have a car. Can we pull something together to carpool and have a nice little outing where we can co-learn and co-teach each other?

There are some of us who really, really love the outdoors and gardening and going to botanical gardens. And then there are folks for whom that’s just not their vibe. Those folks have a careful distance from the outdoors, and that’s something that I have to respect. But, I also want the urban areas where those folks reside to be healthy and safe environments. The built environment can be a site for us to rethink or challenge what nature can and should be.

AMIRIO: I see your garden education work as facilitating narrative change around Black people and our relationship with the more-than-human world. For you, what narratives around the beyond-human realm and Black people are over-indexed? And which are missing within that narrative field?

ASHIA: As a Black person who cannot swim, I am tired of the whole “Black folks can’t swim” narrative. (laughs) I have to put a little asterisk on that because, technically, I can keep my head above water, but I don’t really know how to swim like that.

I’m a bookworm and a history nerd who researches environmental history. Sometimes, folks will say something about Blackness and the outdoors that, in their minds, is very flippant. Then I’ll be like, Actually, did you know that there’s a whole history behind why we say that? And nobody’s looking for that! So, I have to tone it back sometimes. Even when I think about stuff like that—like the whole “Black people don’t swim” narrative—there’s a whole messed-up history behind why Black people don’t really swim or don’t know how to swim: white folks used to throw acid in pools where Black people swam. White folks would also abandon public pools, taking their money with them. Some of my elders even have distinct memories of hearing how white men would drown Black youth.

When it comes to ideas about Black people and nature, the Black American imaginary gets really prioritized, which I completely understand. We live in the United States, so American narratives are the dominant narratives. But, I think about other members of the diaspora, like Caribbean folks, or folks on the coast in Africa—in Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal.

I was just in Senegal in January and I saw Black folks swimming and fishing in the ocean. Americans think that we are the center of the universe, and so American narratives get constantly displayed. But there are so many different forms of Blackness and so many different ways that Black people are engaging with nature. In America, many of us are descendants of enslaved Africans. We also have a lot of African and Caribbean immigrants. There are folks in the Caribbean who are also descendants of slaves, and they have so many different and awesome cultural pathways that don’t get showcased. More of those alternative narratives need to enter our mainstream.

AMIRIO: Let’s talk about mullein. Again thinking about language, it’s been sweet learning about all the common names this one plant has garnered over time. You really get a sense of how this plant has touched so many different human populations over time and has accrued all these different types of intimacies.

I was referencing the book Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask: Anishinaabe Botanical Teachings by Mary Siisip Geniusz. In the book, Geniusz lists some of mullein’s common names:

[F]lannel leaf, beggar’s blanket, Adam’s flannel, velvet plant, feltwort, bullock’s lungwort, clown’s lungwort, Cuddy’s lungs, tinder plant, rag paper, candlewick plant, witch’s candle, hag’s taper, torches, Aaron’s rod, Jacob’s staff, shepherds club, and Quaker rouge.2

How did you first come across mullein? What is its special significance for you? And then thinking about language and common names, if you had to give this plant a new common name that describes your specific intimacy with it, what would it be and why?

ASHIA: Colorado is undergoing a drought, and it has been for many years. A lot of the time, its grasslands are dead, but the mullein in the state stays the same. It’s always pale green with big branches and large stocks. It’s very distinctive on the plains.

Before I was aware of its medicinal uses, mullein was always there. It’s kind of a funny-looking plant; it sticks out. And it’s very fuzzy, so it’s fun to feel. When I was a kid, my mom would have to keep being like, Don’t touch, stop touching that. I always wanted to touch plants.

In 2020, lockdown hit and a lot of people were scared and worried about access to medicine and healthcare. Mullein became an important plant for me and others amid the spread of COVID because you can use the plant to soothe your throat. You can put mullein in some honey, and that’ll help you out. You can smoke it and it’ll help clear your lungs. You can boil it, you can make a tea out of it. It’s a really great expectorant3 that helps you get phlegm out. It helps you cough and heats up the body and gets those lungs cleared. It has a lot of different uses.

Especially in Oakland, around August 2020, the sky turned orange, and the air quality was gnarly. Not only were we reckoning with a new respiratory illness, but then we were also having respiratory issues due to wildfires and air pollution. Communities started making tinctures with mullein and conducting herbal education with young people on how and where to get mullein and other plants that are lung-clearing. During that period is when I started embracing mullein’s herbal, restorative, and health benefits rather than just admiring it as this funky plant that I was so familiar with growing up in the Plains.

Colorado is like many southwestern states—just a square. (Borders are so silly, especially with the way that the Southwest is carved up. It makes no sense.) There are a lot of different biomes and bioregions in Colorado: you have the Rocky Mountains, you have the Plains, and once you get further down to Pueblo, Colorado, you start to get some cacti. While doing some research, I didn’t realize that mullein sometimes gets referred to as “City Cactus.”

I think about City Cactus as almost akin to Black life. Mullein just popped up in the United States. It was brought over via European colonization, and it originates in Eurasia and North Africa. It’s a fugitive plant that’s not native to the Americas: mullein is extremely adaptable and grows extremely fast. I have a fondness for plants like mullein that pop up in disturbed habitats and environments because it takes a really hardy plant to be able to withstand those spaces and make homes of them.

If I had to give mullein a new common name, I’d want it to speak to its resilience—but also the plant’s softness. Maybe I would just call it Beloved in honor of all the different things that it’s done not only for me but also for folks who are reclaiming these long herbal lineages.

AMIRIO: I love that you’re bringing up mullein’s softness and resilience. It’s such a disaster-attuned and disaster-hardy plant. I want to think about this idea of disaster attunement a little bit more.

You mentioned mullein having amazing therapeutic properties, which calls to mind its lineage among enslaved people as a healing plant.4 Right now, we’re in a disaster-heavy moment, especially when it comes to health, wellness, and medicine. We’re seeing many attacks on science, grants being eliminated, and integral research being stopped.

We’re entering this moment of mass medical neglect prompted by the administration that’s ruling us here in the U.S., and it’s time for us to get serious about revering the medicinal properties of our plant kin and allies. However, plants like mullein are commonly considered to be “weeds”—a word often associated with parasitism and uselessness.

Knowing what we’re facing right now, knowing the stakes of this moment, on the level of language, how do we get away from the language of “weeds”? And culturally, how do we reimagine herbalism and foraging as activities that aren’t niche but skills and spaces of knowledge that we can all benefit from—especially now? And herbalism and foraging are in all of our lineages, right? I don’t think there’s a single human being who doesn’t have an herbal lineage.

ASHIA: Oh, that’s a tall order. It starts, as it almost always does, with divesting from this big Human-Nature split—this idea that Humans are above Nature, that we were put on this earth to dominate and rule over Nature, and that we are completely separate from Nature. It’s the belief that we’re these deified entities and Nature is there to be manipulated to our will. Those are pervasive ideas, especially in Western society.

You see it in the way that our cities are designed. You see it in the way that nature is a place to “go to” rather than something that is embodied by and all-encompassing around us. You see it in our food systems. You see it in what areas are designated as “protected areas.” You see it even in the language of “resource-rich land” and “arable land” or “prime real estate.” You see it in the way that we commodify and value land. These ideas are foundational to the creation of the United States.

I always think of the United States as an invention. It’s a colonial invention.

You had European settlers who were stressed out with what was going on in Europe, and so they came to the Americas and saw it as a veritable Eden. They didn’t think to regard the land as something Indigenous communities had carefully cultivated over millennia. They said, We would like to extract resources from the Americas and basically create a mini Europe.

So, again, America as we know it today is an invention. There’s a big ideological shift that needs to happen to understand that we are living on top of societies that are still rooting and flourishing, on top of land that is begging and showing us in so many ways that it wants to be revered and respected and integrated better into the way we conduct our lives. That’s foundational, and it’s a tough ideological shift.

Then thinking about weeds, they’re oftentimes these plants designated as not useful to humans. Again, there’s a value system. Not only are weeds considered to be not useful to humans, they’re specifically considered to be in opposition to agriculture.

Weeds are thought to take away from what we’re cultivating.

History always has something to teach us. If you go back and you think about the monocultures that we are reliant on today, many of them are foundationally tied to the plantation and thinking of food as a commodity and something to trade. As a result, our food systems in the United States don’t prioritize nutritional value or cultural relevance. We prioritize crops that grow the easiest and fastest and for which we can get a bunch of money. There are a couple of things at play that influence the ways we regard foraged foods or foods with long cultural lineages and how we determine what’s allowed to grow and be cultivated.

Alexis Nikole Nelson5 has spoken about foraging has been banned and restricted. These cultural practices are often deemed illegal, and people aren’t able to participate in them. But people participate in them anyway because, come on: are you really going to tell me that I can’t take a plant from a certain place? There’s a lot of trauma and restriction around what we eat, what we are allowed to do, and what we are allowed to grow.

I think back to that Thomas Sankara quote: “He who feeds you, controls you.” That’s so true, especially as we move further and further into a climate crisis that is threatening our food supply—and is increasing the amount of so-called “weeds,” because many of these plants are able to survive a lot of climate disturbances and changes. Climate change is going to influence not only how we grow, but what we can grow.

Either by force or us getting with the times, we are going to have to start getting creative with the way we feed, heal, and nourish ourselves. Foraging food, plants, and herbs is one way to start creatively thinking about how we can reclaim some of our power and foodways.

Mullein is really powerful and has such a long lineage, like you mentioned, in many different cultures. Most of my familiarity with the plant is related to enslaved folks and how they used mullein. There’s so much plant knowledge—and so much Western science and medicine is derived from it.6 So, getting a little bit more familiar with the plants in our area—by doing those nature walks, for example—is super important.

A lot of folks are in the medical system. As our medical system is being attacked, we’re going to have to start seeing a lot more doctors, nurses, herbalists—or just start treating people for free. And we’re going to have to see a lot of medical professionals refuse to participate in a system that is thoroughly extractive and disrespectful, especially toward those from specific cultural backgrounds.

People in my family—unless something is really, really, really wrong—will not go to the doctor because they’re like, I am not trying to have to dress up super nice and put on this facade just so I can get treated with dignity. A lot of doctors who are starting to see the signs of the times are going to have to draw firm lines around what it means to serve and what it means to do no harm. Connecting back with herbal lineages might be helpful.

I’ll share one more brief anecdote: I was in Cuba in December and I got to meet with some Osainistas. Osain is the orisha that rules over the plant kingdom. The Osainistas get knowledge from Osain through the plants. It’s not something you can study—it’s something you’re born into.

When they cannot figure out what is wrong with someone, or they can’t figure out a particular treatment for an ailment, a lot of Cuban doctors will refer patients to the Osainistas. Osainistas will work with Cuban medical doctors to navigate the overlap between herbal and Western medicines.

In Cuba, there’s a deep reverence and respect for those two healing pathways; it’s very siloed in the U.S. Either you really appreciate Western medicine, and that’s your thing, or you’re an herbalist who doesn’t really engage in Western medicine. America loves its dichotomies, but in Cuba, it’s like a conversation. At the basis of the conversation is, How can we ensure wellness for our people? I don’t know if that is a conversation that is happening in America right now. There’s a cultural perspective shift that has to happen.

AMIRIO: As you were speaking, a word I wrote and kept circling was inventiveness.

One thing I’m intrigued by is how this current administration in the U.S. is being creative in the most cruel way by reminding us that all of this is invented. I can destroy an institution as quickly as I can build one up; I can completely remake a nation in my image.

It’s been devastating, to say the least. And it’s been a reminder that nothing is permanent—as abolitionists have told us forever.

Alongside an aversion to moving beyond binaries, it seems we have an aversion to impermanence. Especially in this moment, amid climate crisis—when we’re being shown that everything’s invented, that nothing is permanent—how do we get to a place of embracing inventiveness and impermanence, especially in service of more justice and equity?

ASHIA: I’m guilty of liking routine. I like being able to know, Okay, I’m going to wake up and go to this place. I’m going to get my coffee, and then I’m going to have a certain guide by which I live my life. And that’s comforting. It can also be really paralyzing sometimes because you’re so adherent to that permanence that when it’s gone, you freeze, and you’re like, I don’t know.

It sounds corny, but the solution is always going to be nature for me. The solution is always going to be reaffirming our relationship to nature, getting people more out in nature, doing healing rituals and somatic engagement with nature. Nature gives us so much. She really is that girl. She’s beautiful. She’s powerful.

This past weekend, when I was just surrounded by trees, I thought about how much calmer I felt, and how much more open my mind felt. We live in an era when there’s distractions at every turn—and, hey, I love me some reality TV. I’m not saying that everybody has to stop doing that, but it’s important to have time to be bored and not distract your brain with something.

If you’re distracting your brain with something, you’re quieting inventiveness and creativity. If you are actively not engaging in anything, your brain is going to make up stuff for you. Now, sometimes that stuff might be some scary stuff—said one scary-brained girl. I understand, but sometimes you have to work through those thoughts and sit with them. I wonder when we stopped being okay with sitting with discomfort. You have to be able to sit with discomfort and work through it.

Also, this is a country that does not reward imagination. It does not reward inventiveness. It does not reward creativity. Even when we’re in school, we’re given standardized tests. Teachers are like, Memorize this. Think about that. It’s really ingrained into us not to use radical imagination and inventiveness. We really have to start reclaiming them—and have a little bit of whimsy about it. Have a little bit of silliness. That’s one of the reasons why I love working with youth and being with my little cousins. We play pretend all the time.

I am still working that imagination muscle. It’s one of those things: if you don’t use it, you lose it. Being able to constantly find new ways to be inventive and creative and silly and make meaning out of nothing—these are some of the most amazing things that humans are able to do. Let’s reclaim them.

AMIRIO: You mentioned this idea of sitting with discomfort. When I first read Heirloom, there was so much about leaning into different legacies, histories, and feelings that aren’t comfortable.

Also, I was struck—going back to this overarching theme of language—by how enraged certain lines felt. And I want to be careful with that because I recognize the existence of the Angry Black Woman trope. But, the collection’s rage and anger felt interesting.

Heirloom is in this Black ecopoetic tradition, where there’s an emphasis on connection, beauty, and harmony. There is a lot of rage in Black environmental history, but it often isn’t given voice in the Black ecopoetic space. Why did it feel necessary to foreground those rage-full moments in Heirloom?

For example, in “Creation Story,” you say, “every dusk swept day i thank a Black woman’s rage for ensuring my survival”. In “Drapetomania,” “a patient violence lives at the base of my spine.” In “Ocean Song,” “yes, i am livid. i have too much hate in my blood to let go and let God.”

And I love how you also give voice to the more-than-human world to be fucking angry, too. In “On the Outskirts of Eden,” you write: “my gut is filled with / vengeful / microorganisms.” So again, why was foregrounding anger and rage necessary in a work like Heirloom?

And going back to these ideas of inventiveness, play, and whimsy, in my imagination, mullein harbors anger due to being simultaneously vilified and revered for so long. What do you think mullein’s rage looks and sounds like?

ASHIA: One of my favorite facts about mullein is that it can produce hundreds of seeds—and these seeds can lay dormant for decades. I think mullein is clever, and it knows that rage is a conduit. Rage is almost like fire: fire is a reaction. It has to have fuel; it has to have combustion. Fire needs other components to exist. Mullein is like that. The plant produces all of these seeds, but those seeds know, Oh, I’m not in safe ground. Or, I’m not in a good area where I can germinate and grow. I’m going to wait and bide my time.

Going back to the idea of the Angry Black Woman trope, I grew up going to a predominantly white school. When I did anything there, I was received as angry or full of attitude or sassy. I was constantly trying to prove otherwise—and that became so exhausting. I am okay now. I’m at a place where I’m OK with saying, Hell yeah, I’m angry. Have you seen what’s going on? Why are you not angry?

Everybody has their own emotions and their own way of processing them. For me, anger is the first emotion that emerges, and then I have to poke behind the anger to see what the real emotion is feeding the anger.

Anger and grief are very much intertwined for me. I read about the colonial decimation of bison, which facilitated Indigenous genocide in the Great Plains, or I read about a Chinese mining company poisoning a river in Zambia, and I get angry. I get so sad because I’m like, It does not have to be this way. It makes my blood boil seeing what we do to the earth and what we do to each other.

Colonial powers, Western powers do not treat the earth like a living being; we treat it as something to extract things from. A lot of times that’s how Black people are treated by an oftentimes apathetic population. It’s like, What can we extract from Black people, whether that be labor or culture or inventiveness? That extraction drains us and makes us angry and bitter. If we can have more candid conversations about anger and the way anger shows up in our lives, we would all be better for it.

Within the canon of ecocriticism and environmental writing, there’s so much talk about sublime beauty and romanticism. Lots of this removes humans from nature, as if the only way nature can be beautiful is without human influence. Amid climate change, we’re seeing more dystopian and post-apocalyptic narratives. I think these perspectives are two sides of the same coin: what does it say when the only way we can think of human engagement with nature is nature punishing us, or us being completely separate from nature? Anger has a place in all of that storytelling.

I don’t think you can be as well-read in history as me and not be angry. You know what I mean? (Iaughs) I remember when I was in college and I was taking this class on American environmental history and we were learning about the violence seen on banana plantations in Latin and Central America. I wanted to walk out so bad. I remember saying under my breath, This pisses me off so bad. The white guy next to me was like, Why? That lack of understanding is what we’re contending with in a lot of environmental and ecological spaces. Environmental violence has happened to people—and it continues to happen to people. I don’t know where you want me to put my emotion when I see it still going on.

AMIRIO: You mentioned the relationship between anger and grief. What kind of intimacy do you see between anger and inventiveness? How can the two work together and be generative?

So often, anger, especially when it’s seen among Black people, is thought of as stagnating or unproductive. But, borrowing language from you, anger can be a conduit or bridge to help us build towards that inventiveness that we keep mentioning.

ASHIA: Going back to what I was talking about with my young people, the minute that a Black child is seen as disruptive or non-obedient, they are perceived very differently from non-Black and white children who exhibit those same traits. Enacting that differential treatment is ingrained in us, whether you’re living in a predominantly Black, multicultural, or predominantly white community. Black anger is scary to a lot of people, regardless of whether we want to admit it.

If you find ways to channel your anger, that can be incredibly productive. Unfortunately, a lot of times we don’t have the opportunity to do that. And that’s when it becomes stagnating. That’s when anger becomes lashing out and you start harming people around you. There is somewhere you want this energy to go, but oftentimes, there is nowhere for the energy to settle.

It’s critical to create ways for us to transmute anger, transmute grief, and talk about our emotions and process them. We need to ask each other, Why are you so angry? Instead of saying, Stop being angry, stop crying, or I’ll give you something to cry about. Stuff like that keeps anger being a stagnating force. That feeling is energy. Energy’s gotta go somewhere—and it’s going to go somewhere.

Being outside, dancing, doing some kind of movement, being in community with people who aren’t going to police your emotions—all of that is so healing and generative not only for Black youth, but for Black people as a whole. We’ve gone through so much, and we continue to go through so much. Some Black folks think that they have achieved the American Dream and that everything is okay. However, sometimes I talk to ‘em, and they’re still unhappy.

Have you seen the movie “Do the Right Thing”? I love the “love and hate” conversation the character Radio Raheem has with his rings. He talks about those forces being at odds with each other, but I think they feed into each other. I think they’re siblings, and if you’re careful, the love you have for your people and the rage you have for their conditions—when you pair them together, that can be a very powerful force for change.

AMIRIO: Could you talk about the idea of ecotage, which you’ve discussed in your newsletter ecotage echoes. Could you talk about what ecotage is and how it could be a practical manifestation of what you’re gesturing to—rage becoming loving action?

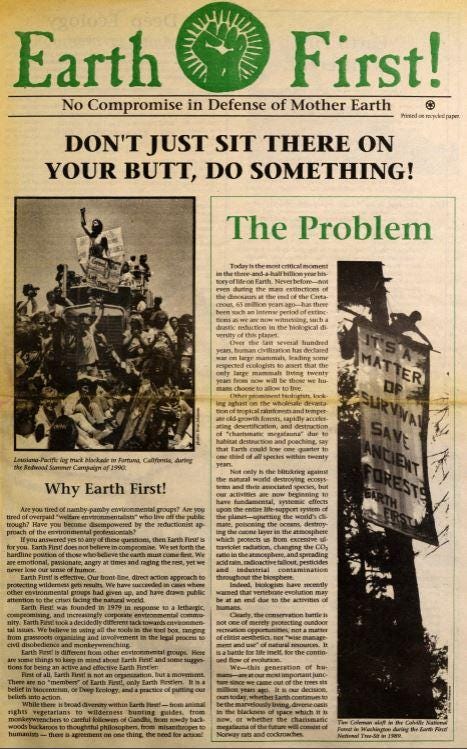

ASHIA: Ecotage is sabotage or revenge for ecological, environmental purposes. It was popularized in the 70s during that big environmental wave where radical folks and organizations participated in what was called “eco-terrorism.” Those folks were setting oil rigs on fire and burning down infrastructure. Those actions became “unacceptable” ways of doing environmental activism.7

Despite white activists getting the most coverage for practicing ecotage, it, for me, is rooted in marronage and ancestral Black practices of divesting from Western hegemony. Ecotage was simultaneously a spiritual and grounded endeavor. Guided by cosmological patterns, slave rebellions and revolutions were land-based struggles. Many rebels would kiss the earth before they went into battle. I also think about the Black Panther Party—especially the co-founder, Bobby Seale, who in 1971, at the “Free John Sinclair” concert in Ann Arbor, Michigan, said, “The only solution to pollution is a people’s human revolution.” One of the reasons why ecotage is a part of the name of my Substack is because I want to think of inventive ways, rooted in ancestral methods, of divesting from a system that is so thoroughly extractive—while also recognizing that this is a system that expands. It does not crumble.

People often think, Oh, we’re in late-stage capitalism. The Empire is crumbling, I’m just going to sit back and watch it collapse. However, the Empire crumbles, fractures, and then strengthens itself. It learns from its mistakes. So what do we need to learn from our mistakes? What are ways to keep the momentum of resistance going?

And we need to make sure that we’re not committing to reformist principles but thinking about what a world in which we have equitable nature-human relationships looks like. Getting to that world means becoming comfortable with enacting extralegal modes of insurgency—which we have a long history of doing. Reclaiming our power and modes of insurrection allows us to not only channel our rage and anger, but also build on a love of environment, a love of people, a love of future, a love of self.

If you have a vision of what could be, it becomes a lot easier to see what needs to be done in order to make that vision a reality.

AMIRIO: I want to think about the state of language at this moment, which is really precarious.8 I’m curious about your take, especially as a poet and writer.

Right now, language is being censored to deny care, citizenship, and humanity. So much language coming from our communities, on the margins, outside the center, has been weaponized. For example, I’m thinking about how the language of DEI has become a site of struggle, or how sustainability messaging has been co-opted by companies that champion fossil fuels.

Also, in some ways language has lost a sense of potency, especially when we’re trying to urgently call people to action in this moment of climate crisis. I think about how, for example, as we see the quicker succession of disasters and they become more mundane, certain words aren’t resonating with or viscerally impacting people. Specific terms and phrases—“wildfires,” “flooding”—feel a bit dead or more flattened because of the moment that we’re in.

Thinking alongside writer Lauren Markham in her book Immemorial, I’m intrigued by the “possibilities of a shape-shifting language to match the shape-shifting world.”9

What new language do we need at this moment? With that question, I’m curious about interspecies endeavors, and I’m wondering what it would mean to create that new language with mullein or another species. I’m fascinated by linguistic exchanges between species, which are always happening, so what new language do we need, and how can we build that new language with mullein and other species that aren’t human?

ASHIA: I’m thinking back to mullein—and I didn’t even get to really talk about how great mullein is for so many other things.

AMIRIO: Bring that all in!

ASHIA: It’s in a lot of Native and Afro-Indigenous traditions. If you smoke mullein before going to bed, it’s supposed to be a conduit between the ancestral and spirit worlds and our world. It’s a way to commune with and learn from the ancestors and think through things.

I most enjoy mullein as an expectorant. A lot of times when we talk about environmental and social issues and climate catastrophe, there’s always this idea of like, Oh, well, if we just love a little harder, if we bring each other together, we will withstand this. I’m less interested in withstanding our circumstances and more interested in what needs to be coughed up, what needs to be expunged. When I read a work like The Salt Eaters by Toni Cade Bambara, it deals with healing after a crisis—and part of that healing is sweating out the bad stuff. “Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well? […] Just so’s you’re sure, sweetheart, and ready to be healed, cause wholeness is no trifling matter. A lot of weight when you’re well.” Minnie Ransom, the central healer in the book, tells that to Velma—a Black activist recovering from a recent suicide attempt. It’s important to invest in community-building, the caretaking work, and supporting each other—one hundred percent. But what is the thing lodged in our chest that needs to be spat up? I think if Heirloom was a plant, it would be mullein. It helps catalyze that purging.

That expunging process is visceral. And I exist a lot in the visceral: in the nasty and the mucky and with the species that are not charismatic and are considered gross or parasitic. So many kids are obsessed with caterpillars and butterflies, and I was, too. I was also really fascinated by spiders. I love watching spiders eat other bugs. (laughs)

AMIRIO: You did mention being a scary-brained person. (laughs)

ASHIA: I’m fascinated by cockroaches. I’m fascinated by decomposers—the unsung heroes who really do the work of breaking down the muck and transferring its energy into something beneficial and useful. Mullein acts in a similar way for us. The plant gets us to purge and expel the historical lies that we’ve been taught about Western exceptionalism.

After you cough, after you hack up phlegm, you feel better. That’s the first step towards healing. Language that normalizes climate catastrophe and disaster—it’s numbing. Mullein is not numbing. You take some mullein before bed, and you’re going to be sweating. It is going to try to get something out of you.

I often speak with a certain sense of urgency that isn’t supposed to be fearmongering. I’m just a very matter-of-fact person when I’m talking about climate and social issues. There’s a matter-of-factness and understanding that we need to embrace around how grotesque our reality is. It is saddening, it is terrifying, and it is grotesque. It is an affront to us as a population—and us as descendants of cultures and diasporas that lived in harmony with nature before the advent of the United States and colonization.

Some people say, I want to go back. I want to go forward. It’s like the Sankofa10 principle: I want to bring lessons from the past with me forward. The only pathway is forward. But to go forward, first, you’re going to have to cough up some stuff. You’re going to have to sweat out some stuff, and mullein can help you do that.

AMIRIO: I want to end on a broader question. I love you bringing up that mullein is an expectorant—there is this interaction with the lungs and our capacity to breathe.

I always bring up that one of my favorite words is conspiracy because the root word—conspirare—relates to the idea of breathing together. There are all these ideas surrounding mullein—the lungs, breathing, ecotage, anger, inventiveness—that bring to mind conspiracy and breathing together.

How can we work conspiratorially with mullein? You’ve spoken to this question throughout this entire conversation, but can you put an underline beneath how we can be conspiratorial with mullein as our ally?

ASHIA: Absolutely! Mullein, in my home state of Colorado and parts of California and Hawaii, is considered a noxious weed, which means it’s believed it should be removed when you see it because it negatively impacts “native” flora and fauna. Every plant—everything—has its use, has its function, has its own knowledge. You just have to listen to it and uncover what it can teach you and what you can learn from it. That’s one way we can work well with plants considered “invasive” and weeds.

Anytime I see mullein, I pull it up: I wait until it’s dry, and then I crumble it. I put it into tea, I stuff it into pillows, I distribute it to other folks. Its softness can be deceptive because it has these tiny little hairs that can be both topical and ingested irritants. So you’ve got to know how to work with the plant and process it properly to remove the hairs.

Instead of believing everything is fraught and horrible, we can work with plants by doing deep listening, devotional attention. Right now, we just need to start from scratch, and part of starting from scratch is recognizing where you’re at, using the tools that are at your disposal, and listening to the world that’s around you.

Ashia’s Recommended Resources

Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes through Indigenous Science, Dr. Jessica Hernandez

Black on Earth: African American Ecoliterary Traditions, Dr. Kimberly Ruffin

M Archive: After the End of the World, Dr. Alexis Pauline Gumbs

Blood in My Eye, George Jackson

Mules and Men, Zora Neale Hurston

Working the Roots: Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing, Michele E. Lee

Learn More About Ashia’s Work

Website: ashiaajani.com

Substack: ashiaajani22.substack.com

Social: @ashiainbloom

Mary Siisip Geniusz (citing Euell Gibbons), Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask: Anishinaabe Botanical Teachings, p. 184

Mary Siisip Geniusz, Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask: Anishinaabe Botanical Teachings, p. 184

As shared by the Cornell Botanic Gardens, “[e]nslaved healers made remedies with mullein leaves for treating congestion due to colds as well as other respiratory conditions. Mullein tea was also a popular remedy among enslaved people for treating kidney diseases. Crushed leaves applied as poultices helped to relieve inflammation associated with arthritis and rheumatism.”

Amirio: Listen to me chat with Alexis about the U.S. food system and more here for Loam Listen.

Amirio: Learn more about Western medicine’s indebtedness to plant life in this past PLANTCRAFT missive with herbalist Suhaly Bautista-Carolina.

Amirio: Alyssa Battistoni recounts how ecotage efforts of the 80s and 90s were countered in the United States and UK for Verso: “Throughout the 1990s, Earth First! and [Earth Liberation Front], alongside animal liberation groups like the Animal Liberation Front, undertook direct action, mostly arson, against the likes of animal testing facilities, logging offices, ski resorts, and—yes—SUV dealerships. In response, the FBI named radical environmentalism the primary domestic terror threat. Much of the pre–‘War on Terror’ counterterrorism apparatus was constructed in response: Legal penalties for protest increased dramatically; environmental organizations in both the United States and the UK were infiltrated by state intelligence agents and surveilled using practices pioneered by COINTELPRO. In the UK in the 2000s, undercover police officers went so far as to father children with activists in the environmental movement, in what is—not hyperbolically—described as rape by the state.”

Amirio: I recently had the opportunity to dig into this topic with Shilpi Chhotray, Co-Founder and President of Counterstream Media, for Counterstream’s digital zine, Peace & Riot.

Lauren Markham, Immemorial, p. 10

From the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia: “We can trace the term [sankofa] to its historical Akan root in west Africa, where Sankofa is represented by a bird that moves forward while turning its head back to grasp in its beak an egg: a seed of the future brought from the past. It may also be depicted by the Adinkra symbol of a stylized heart. Both symbols represent an Akan precept that literally translates as ‘go back and get it.’ Sankofa embodies the idea that heritage is a tool with which to build the future—and that we often need to go back to ‘get it’ in order to understand where we’re at now and how to move forward.”

<3 <3 <3 <3

loved reading this! my grandparents were part of an earlier exodus to denver from louisiana in the 60s. they moved when my grandpa joined the army and then a lot of fam followed.

also mullein is one of my plant guides!!